“The Favorite”; the word “choreography”; baroque dance onstage and in the ballroom, in England and in France; Beauchamp-Feuillet notation… and more

The dance historian Moira Goff is author of The Incomparable Hester Santlow – a Dancer-Actress on the Georgian Stage (2007) and of the blog Dance in History https://danceinhistory.com/ . She and I both became friends in 1990, when we realised we had been spending time researching Santlow, whose long career at Drury Lane Theatre (1706-1733) opens up many new perspectives on the dance, theatre, and society of her day. We have both lectured for Dansox and other dance-studies societies. As shown in this conversation, I have often consulted her on a range of dance-historical matters.

Macaulay 1: Moira, you've been working on dances notated by Feuillet for over thirty years. What led you in that direction?

Goff 1: I had always been fascinated by ballet, although I didn’t begin to learn it until I was twenty, and I was seriously interested in history. By accident, I came across a workshop in baroque dance and went along. We learnt one of the many dances recorded in notation – I think it was Mr Isaac’s “The Favorite”, a ballroom dance created for Queen Anne. (Illustration 1.) I couldn’t manage it at all, the steps seemed like ballet but they worked differently both individually and in sequences. For some reason, the style, technique and choreography spoke deeply to me in a way that even ballet couldn’t. I quickly determined to learn as much as I could about baroque dance and I plunged into classes, workshops and summer schools wherever I could find them (then, as now, there were very few people teaching it here in the U.K.). This led to performing, then researching and then writing – not to mention the PhD on Hester Santlow, which I pursued after you made the suggestion.

Macaulay 2: There was a dance in the time of Queen Anne called The Favorite (thus spelt)? How amazing!

Was this known to Ophelia Field in writing her book about Sarah Churchill (Queen Anne’s influential best friend for many years) called The Favourite? The 2018 film of the book - a big hit starring Olivia Colman, Rachel Weisz, and Emma Stone - was thoroughly inaccurate but brought Queen Anne further into public consciousness than for decades.

Queen Anne (illustrations 2 and 3) (1665-1714), a leading character in several plays and films for her friendship with Sarah Churchill (and vice versa), became Queen in 1702. Her reign was one of immense importance for the military victories that Britain achieved against Louis XIV of France, for the political struggle between the young Tory and Whig parties, and for the cultural achievements of the English and Scottish Enlightenment.

Was The Favorite a dance that the Queen performed herself? I had the idea she was not the dancing type. Anne herself suffered from ill health: all eighteen of her children died before she became queen, most in miscarriages; she herself was ill and obese from her thirties onward. It’s the somewhat immobile Anne that Colman portrays in the film of The Favourite (illustration 4)

Goff 2: I doubt if Ophelia Field knew of Mr Isaac’s dances for Princess, later Queen Anne – there is no mention of balls or dancing in the index to The Favourite, nor is Isaac named there. The Favorite is one of the six ball dances by Mr Isaac notated by John Weaver and published in 1706 in A Collection of Ball-Dances perform’d at Court. On the first plate, it is described as A Chaconne Danc’d by Her Majesty, but it probably dates to 1690 or even earlier. Mr Isaac may have been Anne’s dancing master by 1675, when the young princess performed alongside her elder sister Mary in the court masque Calisto. I have never thought that the title might refer to Sarah Churchill, duchess of Marlborough, but the idea is not so far fetched, for other Isaac dances are named for courtiers, including the Duke of Marlborough. The dancing at the court of Charles II and even that of William and Mary, as well as Queen Anne, is well worth detailed exploration.

Macaulay 3: Feuillet published Chorégraphie, ou l'art d'écrire la danse in 1700: Choreography or the art of recording dance in writing. Did he invent the word “Choreography” (to mean dance notation)? Or was it already around?

Goff 3: I think that Feuillet may well have invented the word as a succinct way of both naming and describing the notation. He knew of the 1588 treatise by Arbeau entitled Orchesographie and mentions it in the Preface to Chorégraphie, although he had apparently never seen a copy. Perhaps Arbeau’s title may have suggested Feuillet’s?

It is interesting that in 1706 John Weaver translated Chorégraphie as Orchesography.

Macaulay 4: And do we know how new or old this kind of notation was then?

Goff 4: Chorégraphie set down only one of at least four systems of dance notation developed in France during the 1680s at the request of Louis XIV (illustrations 5, 6, 7). It owes its origins to the King’s own dancing master Pierre Beauchamp (1631-1705), who invented it but neglected to publish it. When Feuillet published Chorégraphie in 1700, he obtained copyright over the system. By the time Feuillet published his treatise, together with the two collections of dances that accompanied it, the system must have been in use for at least 15 – 20 years.

Macaulay 5. You say Feuillet’s was one of four systems of notation in the late seventeenth century? What do you know of the other three?

Goff 5: The most important of the other three systems was that devised by Jean Favier the elder and used to record his 1688 mascarade Le Mariage de la Grosse Cathos. The notation for that work was published in facsimile with commentary by the American dance historians Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Carol G. Marsh, where they also discuss the four systems of notation developed at the French court during the 1680s. Favier’s system uses the music stave and is less visually appealing and directly informative than Beauchamp-Feuillet, although it is better suited to recording group dances.

Another system was that of André Lorin, intended only to record contredanses and used in two manuscripts presented to Louis XIV. The fourth system was created by the dancing master De La Haise but was never published and apparently does not survive - so we know next to nothing about it.

Macaulay 6: I've always assumed that Feuillet’s is a form of notation particularly geared to the subspecies of ballet that had begun to flourish under Louis XIV, with five turned-out positions of the feet and legs (though I think you've shown us that it can include literally turned-in steps too). I've also understood that it stopped being useful when ballet acquired more jumps, particularly on the spot, and when dances in ballet were less concerned with spatial progress and geometrical organisation of the performing area.

But am I misunderstanding it? Was it also used to record the purely social dances of the day?

Goff 6: I wonder why you use the words “subspecies of ballet” to describe what we now call baroque dance? I think of it simply as ballet, in an earlier and different form from the one we know now, but equally sophisticated and providing the foundation for many of the features we associate specifically with modern ballet.

Like all forms of dance notation, Beauchamp-Feuillet (as most people call it now) was devised to record a particular style and technique of dancing and takes for granted certain aspects that were common knowledge at the time but are now difficult for us to recover. Is it significant that this notation was invented by Pierre Beauchamp, who is credited with codifying the five positions still used in ballet? If you take a look at Chorégraphie you will see that it also includes notation for the five turned in “false” positions (which may well have been part of Beauchamp’s own vocabulary as a dancer). There were also pas tortillés, translated by Weaver as “waving steps”, in which the working foot turned in and out as it moved (these steps feature in a range of notated stage dances).

I don’t know about jumps on the spot – Beauchamp-Feuillet notation can certainly notate tours en l’air with as well as without entrechats, although it would be more difficult for it to notate a jump with splits in the air. As for the “geometrical organisation of the performing area”, I’m not sure that this ever disappeared entirely, either for soloists or groups of dancers, although even by the early eighteenth century the steps seem to have been as important as the figures.

A weakness of Beauchamp-Feuillet is the difficulty of notating choreographies for groups of more than four dancers. There is one dance for nine men (a soloist with a “corps de ballet” of eight), but this seems not to have been followed up.

There is some evidence – in particular from the Ferrère manuscript - that choreographers who mounted ballets as they travelled went on using it into the second half of the eighteenth century. The notation was used to record ballroom duets and this was an important (if not the principal) use made of it by Feuillet and his immediate successors. Ballroom and stage dancing at this time shared the same basic vocabulary of steps. Feuillet also devised a simpler form of notation from the same principles, which was used in France to record contredanses including early forms of the cotillon.

Macaulay 7: To answer your opening question, I look on ballet as a form that went back to at least Catherine de Medici (especially her period as queen mother, 1559-1589) and probably went back another century, to the Italian courts of the early and high Renaissance. If we’re right to believe that the turned-out five positions of the feet were new in the time of Louis XIV (1638-1715) - it seems likely that he himself, dancing lead roles in the 1650s and 1660s, had exemplary turnout by the standards of the day - then I’m inclined to see “turned-out” ballet as a subspecies of an older tradition.

Turnout of the legs has varied intensely ever since. Some eminent male dancers of the twentieth century never had much turnout; some famous ballets made very pronounced use of parallel and turned-in positions. We could go off at many tangents here, but, from your study of the era 1650-1750, can you say how much ballet was based on turned-out positions? Parallel and turned-in positions were surely used, but in what contexts, by whom, and to what degree?

Goff 7: Turnout was fundamental to the dance technique and vocabulary published in notation by Feuillet in 1700 and described by Pierre Rameau in Le Maître à danser in 1725. (Illustrations 8, 9.) I can’t help thinking that it was so widely used that turned-in and parallel positions made more impact in performance than they do now. As I mentioned earlier, Feuillet notates the turned-in or “false” positions in Chorégraphie, and they are used fleetingly within some of the dances published in notation. According to surviving notations, they are particularly associated with the commedia dell’arte character of Harlequin – two of his choreographies include a sequence of small jumps which land alternately in a “true” and then a “false” position. Other commedia dell’arte characters are sometimes depicted in turned-in positions (as well as in turnout), so I guess that there was a clear association with “grotesque” dancing.

Parallel positions also appear fleetingly in the notated stage dances and may in some cases hark back to dances of the early 17th century, when the use of parallel feet was the norm. However, the grottesco dancer and teacher Gennaro Magri described five “Spanish” positions in his 1779 Trattato teorico-prattico di Ballo. These correspond to the familiar turned-out positions, but the feet are in parallel. Earlier notated “Spanish” dances, i.e. dances by French choreographers using French steps, make use of sequences in which the dancer moves in and out of parallel positions. Magri’s “Spanish” positions may have been used and codified many years before he wrote about them.

Macaulay 8: Can you describe what degree of turnout was desirable? Can you discern any evidence of turnout much beyond 90 degrees (45 off the centre line)? And do we know how it was for dancers who could not achieve that degree of turnout?

Goff 8: The Beauchamp-Feuillet system routinely show foot positions with a right angle between them, i.e. a turnout of some 45 degrees, but most baroque dance practitioners accept that this is a notational convention and does not necessarily prescribe the degree of turnout used by individual dancers. Pierre Rameau, who was writing about ballroom dancing, does not specify the degree of turnout, saying only that the legs must be turned out equally. There is so little commentary on the performances of dancers between 1650 and 1750 that it is impossible to answer your last question from evidence. I suggest that lack of turnout would be overlooked if the dancer was otherwise a gifted performer.

Macaulay 9: Could Feuillet notation be used, in theory, to record such later social dances as the waltz?

Goff 9: It could certainly be used for the early 19th-century waltz, which derived its basic step from baroque dance and added a wider vocabulary of steps from the same source. It would be interesting to see if it could cope with the polka or the mazurka, as we know them from 19th-century English and French social dance manuals. Perhaps it could even be used to notate the petit allegro steps and enchaînements of modern ballet, too.

Macaulay 10: Had there been notation systems before?

Goff 10: Beauchamp-Feuillet was the first fully symbolic dance notation system to come into use. Earlier attempts at notating dance going back to the 15th century had used a few symbols alongside verbal explanations and musical notation.

Macaulay 11: Thanks to your reconstructions, I feel I have a whole new sense of the French ballerina Marie-Thérèse de Subligny (1666-1735) and the English star dancer Hester Santlow (c.1690-1773) - and those are women whose careers I had already researched from other points of view. The notation records individual dances that those women performed in public. Which other dancers had dances recorded this way?

Goff 11: There are three collections of notated stage dances in which the dancers are named: two for dances by Guillaume-Louis Pecour, published in 1704 and around 1713, and one for dances by Anthony L’Abbé, published around 1725. The 1704 collection of 35 of Pecour’s dances is dominated by nine duets for Marie-Thérèse de Subligny (illustrations 10, 11) and Claude Ballon (illustrations 12, 13). She also has three solos, while Ballon does not otherwise feature in the collection. In fact, while there are five male duets with named dancers, the only male solos included were “non dancée à l’Opèra” and no dancers are named. This suggests that the leading male dancers at the Paris Opéra usually devised their own solos for the stage.

By contrast, the c.1713 collection (which has nine ballroom dances followed by thirty stage dances) has Marie-Catherine Guyot as its star dancer. She has four solos, five duets with David Dumoulin and two with François Dumoulin, plus another five duets with Françoise Prévost. These last are the only dances by Prévost to be notated and published. Mlle Subligny and Ballon have just one duet and she has one solo, which is the famous passacaille to music from Lully’s 1686 opera Armide and carries the information that she danced it “en Angleterre”. This dance is reconstructed and performed more often than any of the other surviving choreographies.

L’Abbé’s c1725 collection of 13 dances performed by leading dancers on the London stage is rather different. The two stars are Hester Santlow and Louis Dupré, with four notated dances apiece. She has a duet with Mrs Elford (another dance to the passacaille from Armide), a duet with Charles Delagarde and two solos. Dupré has a solo chaconne (to music from Lully’s 1684 opera Amadis), two duets with Ann Bullock and one with Charles Delagarde. The other dancer who features significantly in this collection is the young George Desnoyer, who has two solos and a duet with the actress-dancer Elizabeth Younger.

Macaulay 12: There’s so much material here - thank you. I’ll just ask you a little.

Orthodox histories of ballet list Mlle Lafontaine, Mlle de Subligny, and Mlle Prévost as the first three ballerinas of French ballet. Do you feel Marie-Catherine Guyot deserves a bigger place in official histories? Or were those historic three somehow more “noble” or “royal” or classy? What do you infer or guess from notation and other sources?

Goff 12: Yes, I do think that Marie-Catherine Guyot should be added to the pantheon! She was the Paris Opéra’s leading ballerina between Subligny and Prévost (amply demonstrated by her dominance in the c.1713 collection of Pecour’s stage dances). I think that the reason she has been overlooked is that most histories of ballet do not delve into the repertory at the Paris Opéra or its company of dancers: they remain generally unaware of the rich legacy of choreographies in notation. Also, Mlle Guyot was not a “first” like Mlle Lafontaine, nor is there any portrait of her (as far we know), unlike both Mlle Subligny and Mlle Prévost.

I do feel that the time is ripe for a reassessment of all of these women, so that we have a better understanding of them, their dancing and their careers. Not all the evidence we would like to have survives, but there is much more than is generally used.

I guess this is the place to make another point, which is that modern accounts of stage dancing in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries say too little about the male dancers – despite there being such stars as Pierre Beauchamp, Guillaume-Louis Pecour, Claude Ballon, David Dumoulin and Louis “le grand” Dupré, all of whom danced with or choreographed for the ballerinas we have been talking about.

Macaulay 13. I agree that histories of professional ballet in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries should say more about the important male dancers. Do you think that’s because we know less about them as “personalities”? Did society of the day talk more of the women dancers, as it did of Louis XIV’s mistresses, because they attained an eminence seldom achieved by other women?

Goff 13: I think that the focus on the women dancers reflects ballet in the early 20th century, when dance history began to be taken seriously and explored by writers and critics. Their view of ballet and its history was shaped by the pre-eminence of the ballerina established by the romantic ballet and maintained well into the 1900s. As for “personalities” and celebrity, I am not sure that society at large really paid much attention to professional dancers, male or female, but so little detailed research has been done it is difficult to be sure. We have very little to hand in the way of personal testimony or eye-witness accounts of dancers like Prévost, Sallé, Camargo and Santlow to help us. When it comes to research, even now we have barely a handful of full-length and reliable biographies of those individual female professional dancers who have become synonymous with 18th-century ballet.

Macaulay 14: And those male dancers: were they leading the way as both technical virtuosi and expressive artists? In what ways did they advance technique? Do we see them anticipating the expressive reforms of the subsequent ballet d’action?

Goff 14: The notations suggest to me that the leading male dancers were mainly concerned with technical virtuosity, although other evidence – for example about Claude Ballon – suggests that some were also exploring the expression of the Passions in dancing from the early 1700s. I think that the genesis of the ballet d’action needs research that ranges more widely in time (back to the mid-17th century) and area (across Europe and Britain) to uncover the many influences that contributed to it. Noverre was one of very few dancing masters and choreographers to put pen to paper and to publish their ideas, which has given him undue attention and perhaps exaggerated his contribution. His predecessor John Weaver did not work in a vacuum, but drew on both the dance and the drama he saw around him on the London stage. Weaver wrote and published his ideas, giving him an advantage with later dance historians, but I am convinced that his influence was far more widespread and long-lasting than is usually credited.

Macaulay 15: Does the notation distinguish between theatrical dance and dance in more private or informal contexts?

Goff 15: I don’t think that any of the surviving notations, even the dances for the ballroom, were intended for private or informal performances. The ballroom dances were choreographed to be performed publicly in the context of a formal ball, in which everyone present would watch the single couple dancing them. It is possible that some of the solos and duets not given at the Paris Opéra were intended for performance at masquerade balls, by amateurs as well as professionals, but I wouldn’t see that context as private or informal either.

Otherwise, the notated dances in the three collections of stage choreographies of 1704, c1713 and c1725 both resemble and differ from the notated ballroom dances. Some of the latter, notably Pecour’s La Mariée of 1700, may have originated on the stage. In general, the steps and sequences in stage dances are more complex and difficult and there is more ornamentation. Your question is worth more detailed consideration than I can give it here.

Macaulay 16: Françoise Prévost (1680-1741) has an important place in official histories. (Illustration 14.) She has been given as the original dancer of Les Caractères de la Danse and of the Les Horaces scene with Ballon at Sceaux, often seen as a precursor of the ballet d’action. She is also seen as the teacher-star from whose shadow both Sallé and Camargo burst in opposite ways.

What do the notations and other evidence suggest to you about her?

Goff 16: The notations set her alongside Mlle Guyot as a technician, but they also suggest that both dancers had expressive skills. The five duets are very different from one another. The first in the collection of notated dances is a canary (similar to a gigue but with an upbeat that changes the music-dance relationship) for which they seem to have been masqueraders, although the nature of their costumes and characters is not further specified. Then there is a gavotte in which they may have been shepherdesses disguised as huntresses – this dance has a demanding sequence of half-turn and full turn pirouettes. They were shepherdesses again in a musette, which is by turns lively and tranquil. In another canary they were bacchantes and this is one of the few notations which provides additional information – they played tambourines as they danced. Finally there is an Entrée, a duple-time dance called “Air des Polichinels” in the score (the same music is used for a notated male solo) in which, according to the livret, they were Espagnolettes. I have danced all five of these duets and they are demanding and engaging.

Apart from that, I haven’t researched Françoise Prévost, although the dance historian Régine Astier has published some interesting work on her life and career.

Macaulay 17: Santlow - often called Mrs Santlow while still unmarried, “Mrs” being an abbreviation for “Mistress” - was evidently a terrific dancer, and one of remarkable stage longevity, starring at Drury Lane from 1706 to 1733. (Illustrations 15, 16.) From 1719, she was Mrs Booth, wife to the actor Barton Booth. On his death in 1733, she retired from the stage.) I recommend your book on her to all.

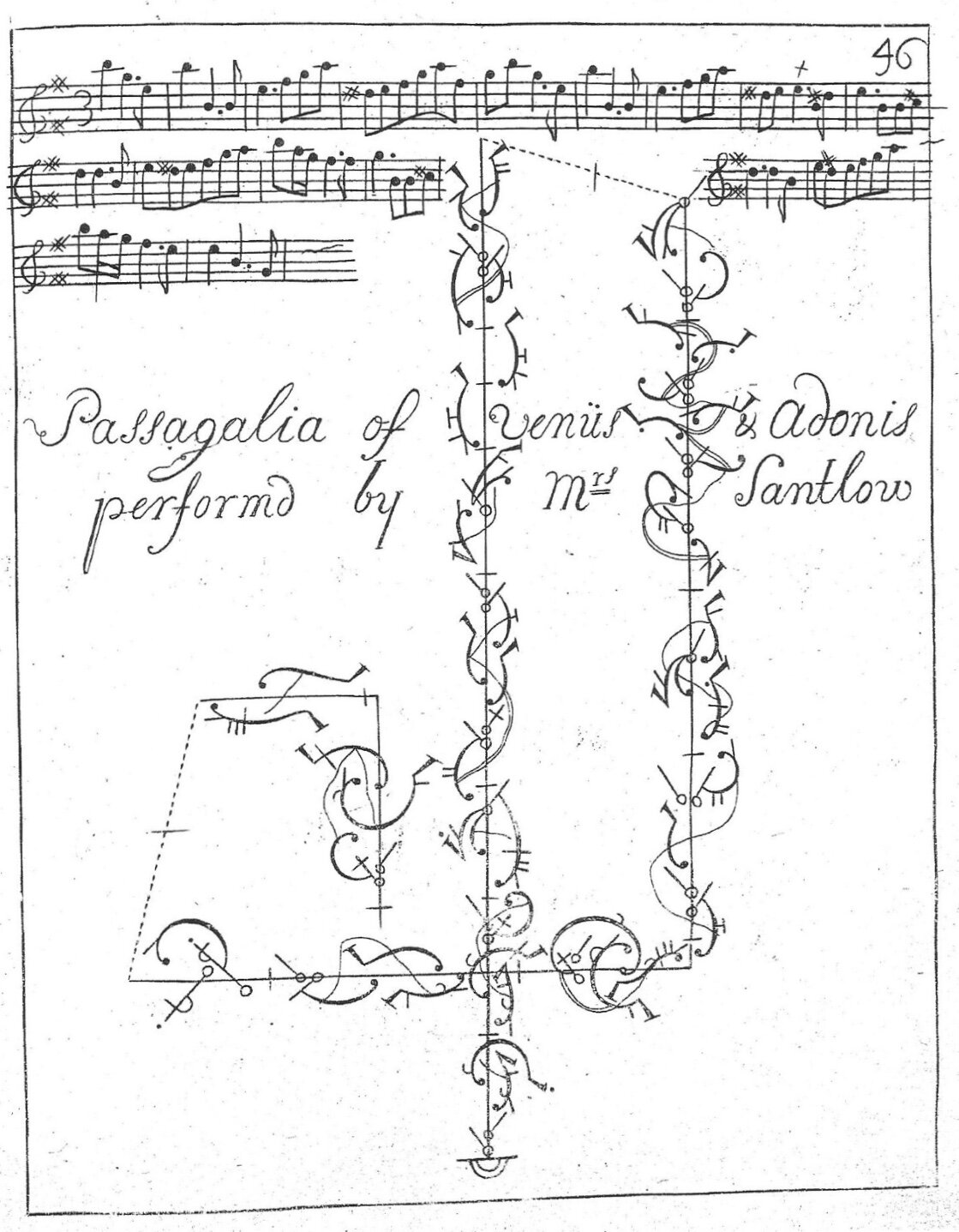

Do you sense from the notations (illustration 17, 18) that she was performing the same basic style as de Subligny and Prévost? Working with such British dancing masters as Weaver and Tomlinson, she surely sometimes exemplified a different English style - but, trained by l’Abbé and appearing often beside Dupré and Desnoyer, did she also exemplify most or all of the French style too? I know some guesswork must be involved here, but you have studied her dances intimately for decades.

Goff 17: Mrs Santlow was undoubtedly in the same league as both Mlle Subligny and Mlle Prévost. She was French-trained, by both René Cherrier and Anthony L’Abbé (who created at least five choreographies for her). However, the context within which Hester Santlow danced was very different from the Paris Opéra – after her early years, she never danced in operas as her French counterparts did. At Drury Lane, she danced in the entr’actes and in afterpieces, both Weaver’s “Dramatick Entertainments of Dancing” and pantomimes. I doubt if any French ballerina of the period was called upon to portray a character in dance as Mrs Santlow did with Weaver’s Venus, although the dances she performed in The Loves of Mars and Venus and other afterpieces were undoubtedly French.

Macaulay 18: You have sometimes reminded me that great dancers would often or always have performed with eminent members of the audience seated onstage; and you have, reasonably, imagined that Santlow and others may well have addressed individual people as they danced. That makes the stage dances of the baroque era feel suddenly very small-scale. But were they also affairs of large-scale projection? Santlow’s performances at Drury Lane were attended, I believe, by Queen Anne, George I, George II, and other members of the royal family. If so, would those royals have been seated in boxes? How far would Santlow and other dancers have had to project? And was there a public also in much more remote upper galleries? Today, much of the thrill of ballet lies in its power of projection; was that developing then?

And did the same rules apply in France? Did certain members of the public sit onstage there too?

Goff 18: The theatres that Hester Santlow and her contemporaries danced in were much smaller, and had smaller audiences, than the present-day Covent Garden or London Coliseum. Drury Lane held 800-1000 people and even those farthest away from the stage were much closer than we are used to. The projection you talk of would have worked very differently. The intimacy of such spaces would have been enhanced by the use of the forestage, the area in front of the proscenium arch which extended to the pit, which dancers would mainly have used and which put them in the midst of their audience. So, projection certainly, to reach the back of the gallery, but nuance too for those sitting much closer.

Royalty would have been seated in the royal box, which was in the centre of the boxes which encircled the pit – placed directly opposite the stage to give the best view of the perspective scenery and effects which were an important feature of productions then. I think that the projection to which you refer must have begun to develop from the late 18th century, when Drury Lane and other theatres were rebuilt on a far larger scale – this must surely have also affected the style and technique of stage dancing.

I’ll have to sidestep your question on whether audience members sat on the stage in France as I don’t know the answer. (It is becoming apparent that there was far more dancing in other venues besides the Paris Opéra than we have realised.)

Macaulay 19: It’s interesting that the notation describes several same-sex duets: male-male and female-female. I believe these were part of ballet going back to the ballet de cour of Louis XIV and perhaps earlier. I remember a period of the twentieth century when ballet’s stage behaviour was so heteronormative that any same-sex duets seemed “daring” or even louche. Any idea what kind of manners, etiquette, characters, emotions, or relationships might have been suggested by these baroque duets?

Goff 19: Same-sex duets were a regular feature of dancing on the London stage as well as in the ballet de cour and at the Paris Opéra. In France, there is the complicating factor that female roles were predominantly danced by men until the advent of female professional dancers at the Opéra in 1681. I haven’t really analysed any of these duets within their operatic contexts, but I doubt if there were any obvious sexual undertones, although there may have been some preferred character types. By and large, these male duets allow for a more obvious display of virtuoso skills with jumps, beats and turns, as the notated dances show. There are some 16 notated male duets.

The one male duet I would like to see, in full costume, is the Loure or Faune performed by Claude Ballon and Anthony L’Abbé before William III at Kensington Palace in 1699. Many of the steps are ornamented and there is a triple pirouette as well as an assemblé en tournant incorporating beats equivalent to an entrechat-six within the final half-dozen bars of music. It presented two of Europe’s finest male dancers in full flight within the intimate setting of a court performance before the monarch who had dared to oppose Louis XIV.

Macaulay 20: What was the point of notating dances associated with individual stars? Were the notations used by aspiring dancers, do you think?

Goff 20: We can only guess why stage dances were published in notation. Underlying the creation of the notation system was the idea of preserving choreographies for the future (although it is not clear whether the aim was to dance them or simply admire them). I think that the publication of collections of Pecour’s stage dances may have been a means of showing off French dance culture to the rest of Europe. We don’t know whether Pecour’s choreographies survived in repertoire beyond their original interpreters.

I’ve wondered if the L’Abbé collection, at least, was designed in part to provide keepsakes – mementos of the choreographies performed by star dancers – as most of the dances are too difficult for amateurs to perform. The notations were, of course, also a means by which dancing masters in Paris and London as well as beyond could learn and teach these dances – although, so far as I know, we have no real evidence that they did so with the stage dances and nothing to confirm that these particular choreographies were performed on stage elsewhere. It is worth mentioning in passing that some of Pecour’s best-known ballroom dances made their way onto the London stage and were advertised as being taught to amateurs over many decades.

Macaulay 21: A few bars of Beauchamps-Feuillet notation were shown at the recent Dansox conference (July 10-12, 2021), seen on line as well as in person. When you contributed to the July 10 session, you remarked in passing on the large expanses of blank white space on either side of the figurations. Would you like to speculate about, or discuss, these?

Goff 21: I often think that the white space around the notation symbols hides the actions, passions and manners expressed by the dancers as they performed the steps recorded for them. When we reconstruct dances, these are the aspects that have to be recreated for they are not set down. The white space speaks for the other sources we must turn to if we want to create a performance and not merely go through an academic exercise.

More prosaically, the notations tell us nothing about the positions of the head or the changing directions of the gaze. They provide the barest of indications about the disposition of the body – épaulement is sometimes shown but may have been used more frequently and have been more exaggerated than the one-eighth turns notated. The symbols do not tell us how high the leg should be raised when the foot is off the floor or describing an ouverture de jambe. Nor do they show how high (or how forceful) jumps should be.

Pierre Rameau (Le Maître à danser, 1725) provides some information about the intricacies in executing individual steps, but a lot is still lost in the white space. The notation hints at, but does not say clearly, where the emphasis should be in a sequence of steps – which are preparatory and which should be highlighted. The notation symbols are very informative and the closest we can come to stage and ballroom dancing in Europe during the early 1700s, but there is a lot of white space around them!

Macaulay 22: As you say, much or all of the upper-body behaviour of these dances is not notated. What sources do you and other specialists use for this this?

Goff 22: I and others use the early 18th-century dance manuals, particularly Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître à danser, although he actually says very little. Some of us (me included) have unconsciously borrowed greater degrees of épaulement from ballet while otherwise accepting that upper body movements were restricted both by the dance aesthetics of the period and its costume.

Reconsidering these factors here, and mindful that Rameau was writing about ballroom dance, I believe that this area needs to be revisited. In the case of female stage dancers, perhaps we need to look more closely at the upper back and the range of movement possible even when wearing an 18th-century style corset – small forwards and backwards bends were, as I understand, a feature of the early romantic ballet.

Upper body movement in general must have been more extensive than the notations indicate, although there is no evidence for this.

Macaulay 23: How musically precise is the lower-body action in Feuillet-Beauchamp notation? Can you tell whether the dancers were expected to respond to the beat or to anticipate it? Those two different musical approaches - even though most dancers do both at times - create a very considerable range of discrepancies in ballet today.

Goff 23: The implication of Beauchamp-Feuillet notation is that all dancers had to be musically precise in a very specific way. However, modern interpretations of the 18th-century dance-music relationship vary. The musical explanations of Feuillet, Rameau and others differ and can be interpreted in several ways.

One area of dispute is the timing of the plié that precedes the élevé in the demi-coupé. Is it on the last beat of the preceding bar or the upbeat to the succeeding bar? The first gives a longer plié and more grounded steps, the second is much crisper and lighter and the plié becomes an inflection and preparation rather than a full movement in its own right.

It is interesting that, in some notated dances, there are steps where the pliés within a pas composé may be shown at the end of one step rather than the beginning of the next (the latter is more usual), suggesting a greater emphasis on the plié movement. When it comes to the dancers of the 18th century, I don’t think we have much if any evidence about their musical timing but I would be surprised if there was complete uniformity. Then as now, dancers differed from one another.

Macaulay 24: Can you speculate on why dances after about 1725 were not recorded? Was the Beauchamp-Feuillet notation unsuitable for the new forms of virtuosity?

Goff 24: Dances stopped being published in notation in France after 1725 but went on appearing in London until the early 1730s and beyond (the latest to survive is a ballroom dance dated, on good evidence, to 1740).

The main reason for the cessation in France was probably the death of Dezais, who was the prime notator and publisher. In England, the death of Edmund Pemberton in 1733 (who fulfilled the same role) more or less brought it to an end (the one later dance may have been notated and published by his son). I am inclined to believe that they had no successors not because of the limitations of the notation system but because their enterprises were not commercially viable (though the reasons for that obviously need investigation).

It is worth noting that ballroom dances were again published in the 1760s and 1770s to 1780s, when Magny and then Malpied were active – some of their notations, notably the Menuet de la Cour, were linked to stage choreographies.

Macaulay 25: I recently read an Instagram post that said the ballet of the seventeenth century was limited by its costume. Hmmm…. There's much to say here.

First of all, am I right that some women's dances contain such steps as a full tour en l'air that are by no means what we associate with the attire of Louis XIV's court? And that some of the footwork is so detailed that the women dancers must have either pulled their skirts up or worn shorter dresses?

Goff 25: This idea that seventeenth-century ballet was limited by its costume needs close attention by specialist dance and costume historians, which I believe would refute it. The supposed restrictions of the stage costumes of female professional dancers similarly need detailed, open-minded research using a wide range of sources.

Ideas about how female dancers were dressed centre on two images in particular – the print of Mlle Subligny dancing in an elaborate floor-length gown (illustrations 10, 11) and Lancret’s portrait of Mlle Camargo (illustrations 19, 20, 21) in a much shorter and lighter skirt. (See also illustration 22.) The notations for solos by Mlles Subligny and Guyot, as well as Hester Santlow, provide evidence of a technique and vocabulary with much emphasis on the feet and lower legs. They not only have many jumps but also a range of aerial beaten steps, including entrechats and cabrioles. The tour en l’air to which you refer is notated for performance by Mrs Santlow in L’Abbé’s Chacone of Galathee, the duet he created for her and Charles Delagarde. Mlle Guyot has assemblées en tournant with a full turn in the air. She was evidently a fire-cracker of a dancer, and might well have pre-dated Camargo in being able to ‘dance like a man’. From the evidence provided by the notations, alongside other visual evidence from prints and paintings of the time, I simply do not believe that women wore heavy floor-length dresses when they danced on stage.

I have a question of my own. Could the well-known Lancret painting of Camargo have itself been the source of the tale about her shortening her skirts beyond those of the other female dancers of her time?

Macaulay 26: I’ll have to give that thought! The best known pictures of Subligny and Camargo have them dressed in formal attire. You suggest that they wore shorter and surely lighter dresses. I think there are a few pictures of less celebrated women dancers that support this, am I right?

Goff 26: For most of the 18th century, we have very little pictorial evidence for dancers whether male or female. There are four images I turn to when thinking about what female professional dancers wore on stage. I will have to include some pictures.

The first (illustration 23) is an engraving of Terpsichore by Nicolas Bonnart dating to the late 17th century.

Another (illustration 24) is the copy of the Ellys portrait of Hester Santlow as Harlequine which she herself owned.

A third (illustration 25) is the engraving that was used as a frontispiece to Harlequin-Horace; or, the Art of Modern Poetry published in 1731, which shows Francis Nivelon and Mrs Laguerre dancing together – her skirt is tucked up in front nearly to her knees.

There is also a small oil painting (illustration 26) by Marcellus Laroon the younger, showing a couple dancing together on what appears to be a small stage. This is undated but may belong to around 1730. The female dancer’s skirt is reminiscent of Terpsichore’s.

Even these images do not prove anything – there is still much research needed to interpret them, as well as to try to find others.

Macaulay 27: Could it be that Camargo was not the first dancer to show her ankles, as legend now has it, but that she was the first to shorten the more formal dresses to include the display of ankles ?

Perhaps here we’re talking about different genres of dance that would have demanded different genres of costume. Subligny surely did do some or many dances in the full-length dresses seen in her best-known pictures. I’m assuming she also wore shorter, lighter dresses for different dances, but that no picture of those has reached us. Yes?

Goff 27: I actually don’t believe that the portraits of Subligny are intended to show her as she was when dancing but to portray her as a leading ballerina at the Paris Opèra, with a suitably grand dress and pose. They are symbolic rather than realistic. I am sure her costumes did vary according to her dancing roles, but I cannot see her dancing anything with complex steps in a frock that long and that formal.

As for Camargo – do we have any contemporary evidence for her shortening her skirts beyond those of other female dancers of her time or is all the testimony from later periods? I would like to see far more research done on both ballerinas, their contemporaries, their repertoires and both stage and fashionable attire of the time, which might begin to untangle the messages within both images. We currently have no other dancing portrayals of either ballerina (the various Camargo paintings are all by the same artist and show her in the same pose) and one each isn’t enough to allow us to draw firm conclusions. Nor do we have many images for other dancers, male or female, from the period, so we are mostly making guesses about stage costumes for dancers.

Macaulay 28: I've heard you say that even people with extensive modern ballet training would be taxed by some of these numbers. Can you explain why and how?

Goff 28: Leaving aside the vexed question of exactly what was the style and technique of baroque dance, which excites pointed discussion among researchers and practitioners, I can only refer to my own experience. There are three areas that dancers trained in modern techniques, including ballet, find challenging: the steps; the figures; and the relationship between the music and the dance.

For me, the step which lies at the heart of baroque dance is the demi-coupé, which has all but disappeared from modern ballet. It requires the dancer to make a preliminary demi-plié, step onto a bent leg, straightening it and rising as the weight is transferred, then bring the feet together in a first position with both legs straight to balance on the ball of one foot in ‘equilibrium’. The demi-plié comes on the upbeat and the equilibrium or balance is achieved on the downbeat or first beat of the bar. The demi-coupé takes much practice to master and I have seen a good number of professional ballet dancers struggle with it. It is the first element of the baroque pas de bourrée and appears in many other steps. The demi-coupé is the foundation for the aplomb and sense of “suspended momentum” in baroque dance.

The figures are the paths traced by the dancer or dancers within the dance space in the course of the choreography. The notated figures are not an exact representation of these paths, but they do reveal the changing spatial relationships between the dancers and their audience whether on stage or in a ballroom. When there are two or more dancers, they also show how the dancers relate to one another spatially. The skills required to interpret and perform these figures with appropriate accuracy are not among those routinely taught to modern dancers.

The music-dance relationship is complex. The notated dances link the two at the level of the bar as well as phrase and musical section. Baroque dancers need to be thinking simultaneously at all three levels. Music and dance phrases do not always coincide and the latter are sometimes reflected in the figures as well as the steps. I should also point out that there is often little repetition of steps within baroque choreographies, even though the music has a specific repeat structure. Some choreographies have no repeated sequences at all.

Macaulay 29: I love all this. Can I ask you more about the demi-coupé? All this is in heeled shoes, I take it. So when the dancer steps onto a bent leg, does he/she place both heel and ball of foot down at the same moment? Or does it have a more piqué emphasis onto the ball of the foot? Does the notation make the difference clear or is this one of the bones of contention between today’s baroque dancers ?

Goff 29: Rameau depicts his male ballroom dancer in shoes with a small heel - and most baroque dance practitioners nowadays wear shoes with a flexible sole and a small heel. In the demi-coupé you place the ball of the working foot in front in a small fourth position with the heel raised and transfer your weight onto it, straightening the leg without lowering the heel and bringing the other leg beside it to end in a first position balanced on the ball of one foot. You only lower the heel as you do the plié to begin the next step. The notation shows that you plié before you make the step and rise when you have taken it, which is perhaps at odds with Rameau’s later description of the mechanics of its performance.

Many dancers now treat the demi-plié as if it were a piqué, stepping directly on to a straight leg. Both the notation and the written description leave room for differing interpretations – there is no way of knowing which one is closest to early 18th century practice.

Macaulay 30: You describe matters of musical timing with great precision, which I love - but I wonder how universally such precision operated. I’m very used to watching how, in Act One of Giselle or Act One of The Sleeping Beauty, different ballerinas use the downbeat differently. The step is piquée arabesque, but some (chiefly the post-1950 Russians) use the downbeat for the tendu preparation, while others (notably British and Americans) for the full-arabesque arrival on one foot. I imagine different baroque dancers and/or different schools/styles likewise differed. Are you describing a particularly French emphasis?

Goff 30: I am using interpretations derived from study of Feuillet’s Chorégraphie and Rameau’s Le Maître à danser, so I suppose these are “French,” although the dance style and technique they describe were known and practised widely in Europe. For me, that musical precision and the intertwining relationship between music and dance are a key part of the powerful appeal of baroque dance. Sadly, we know almost nothing about the performance of individual stage dancers during the 18th century. However, current research is beginning to uncover many variations in the musical timing applied to individual steps (not surprisingly, the minuet step is prominent among these) and building on earlier less detailed ideas about national differences within this shared ‘French’ dancing. So, I think we can reasonably surmise that there was a wide range of performance practices across Europe’s theatres (and beyond) and among the dancers who moved between them and that these would have extended to matters of musical timing.

1: The Feuillet notation for “The Favorite, a Chaconne Danc’d by Her Majesty” i.e. Queen Anne when she was Princess Anne. The dance was performed c.1690, when Anne was sister to Queen Mary II and Mary’s husband William III. This notation was published in 1706. We do not know who partnered Anne here.

2: Queen Anne (1665-1714) as portrayed by Michael Dahl in 1705.

3: Queen Anne in 1685 as Princess Anne (daughter of James II), Princess of Denmark (wife of Prince George of Denmark), around age twenty, painted by Jan van der Vaardt and Willem Wissing. Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

4: Olivia Colman as Queen Anne in the 2018 film “The Favourite”. She won the Oscar for Best Actress.

5: Louis XIV of France (1638-1715), dancing the role of Apollo (Apollon) in his early teens in Le Ballet de la Nuit, a ballet de cour.

6: Louis XIV, in his mid teens, dancing the role of War (La Guerre) in The Marriage of Peleus and Thetis (1654, Les Nopces de Pélée et Thétis), a ballet de cour.

7: Louis XIV (the king, Le Roy) as Apollo (Apollon) in a ballet de cour.

8: An illustration from Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître à danser (1725), a manual on the ballroom dances of the day.

9: Another illustration from Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître à danser (1725)

10: An often reproduced engraving of Marie-Thérèse de Subligny (1666-1735), leading female dancer of the Paris Opéra, dancing. Because the known depictions of Subligny show her in the full-length dresses of a court lady, it has often been assumed she always dressed thus for ballet, but the notations and descriptions of her dancing suggest she, at least for some numbers, wore shorter or different attire: her feet were seen turning in and out, moving at speed.

The patches on her face, bizarre to modern taste, were part of Versailles fashion. The fashion is mentioned in a letter by Louis XIV’s sister Liselotte, duchesse d’Orléans.

11: A collage arrangement of the same picture of Subligny, made by the artist Jean Mariette (1660-1742) in the early eighteenth century.

12: Claude Balon (or Ballon, 1671-1744), leading male dancer, choreographer, and dance teacher, of the Paris Opéra for many years, in an engraving.

13: Claude Balon (Ballon). His first name has often been incorrectly given as Jean.

14: Françoise Prévost (1681-1744), leading female dancer of the Paris Opéra, depicted c.1723 - presumably with considerable artistic license rather than accuracy - as a bacchante.

15: A now well known painting of the leading London dancer Hester Santlow (c.1693-1773) in the Harlequin dance for which she was renowned.

16: Hester Santlow, both actress and dancer, was famous not only for her dancing but for her looks. Of the few portraits of her, this perhaps gives the best idea of her personal loveliness.

17: The Feuillet notation for the Passacaglia from “Venus and Adonis” danced by Hester Santlow. From Anthony L'Abbé’s A New Collection of Dances, published around 1725 She was known as “Mrs Santlow”, but the word “Mrs”, short for “Mistress”, applied to unmarried women as well. When she married (to the actor Barton Booth), she appeared as “Mrs Booth” for the final fourteen years of her career. When her husband died in 1733, she was probably about forty years of age; she immediately and permanently retired from the stage. Her long retirement lasted another forty years.

18: The Feuillet notation for the Chacone (Chaconne) of Amadis as performed by Mr (Monsieur) Dupré (Louis Dupré), who appeared in London for some years opposite Hester Santlow and in the innovative dance-dramas of the choreographer John Weaver. It was long assumed that this Louis Dupré was the later and more celebrated Louis “le grand” Dupré, who enjoyed a long career as the leading man of the Paris Opéra; but this has now been disproved.

From Anthony L'Abbé’s A New Collection of Dances, published around 1725.

19: Marie-Anne Cupis de Camargo (1710-1770), as portrayed by Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743) c.1730. This version hangs in the Wallace Collection, London. Lancret made at least two other very similar paintings of Camargo: see 20 and 21.

20: Marie Camargo, in another painting of her dancing by Nicolas Lancret. (See 19 and 21.) This one hangs in Berlin.

21: A third painting by Nicolas Lancret of Marie Camargo dancing. (See 19 and 20.) The differentiating feature here is that she has a male partner, though his name is unknown.

22: These pair of statuettes of Marie Camargo - differently arranged in the two photographs - are in faience (glazed ceramic ware). Probably modelled on Lancret’s painting, they are believed to have been made c.1745. Haughtom Gallery.

23: This engraving of Terpsichore as the third muse is by the engraver Nicolas Bonnart (1637-1718). Made in the late eighteenth century, it shows the muse of dance with skirts revealing her ankles.

24: Hester Santlow herself owned this copy of the Ellys painting of herself in the Harlequin dance (see 15). Her skirts end higher in this version, revealing the ankles.

25: This, published in 1731, shows François Nivelon and Mrs Laguerre dancing together: her skirts are tucked up to almost knee-level. This was the frontispiece to Harlequin-Horace; or the Art of Modern Poetry.

26: This small oil painting, by Marcellus Laroon, may date from c.1730. The couple are on what seems to be a small stage; her skirts show her ankles and calves.