Albert Reid on Merce Cunningham - eighty-nine answers to eighty-nine questions

Albert Reid danced with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1964-1968, creating roles in several important and enduring dances. He toured the world with the company in 1964 (with John Cage , David Tudor, and Robert Rauschenberg as part of the tour). Over the years, he danced alongside Cunningham, Shareen Blair, Carolyn Brown, William Davis, Viola Farber, Barbara Dilley Lloyd, Deborah Hay, Sandra Neels, Steve Paxton, Valda Setterfield, Gus Solomons Jr, and other luminaries. He was in the first cast of works designed by Frank Stella, Jasper Johns, and Andy Warhol: notably “How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run”, “Scramble”, “RainForest”, and “Walkaround Time”, all works danced since Cunningham’s death. He also became a teacher of Cunningham technique for many years. As both dancer and teacher, he left an enduring impression. His Cunningham dancing may be seen in film of several dances; he also appears in the 2019 film “If the Dancer Dances” about the Petronio “RainForest” production.

He and I met in 2011. In 2015, I interviewed him by email about Cunningham’s “RainForest”, when I was writing about this being staged for the Stephen Petronio Dance Company. During the course of 2019-2021, he has answered a great many further questions of mine by email, taking care with his answers. (I long ago learnt to respect the memories of dancers who say frankly “I don’t remember” about some parts of their past; Reid is one of these.) I hope that my pleasure and gratitude are evident in this prolonged interview/conversation.

Alastair Macaulay 1. In case it helps, here is a list of works in which you created roles:-

“Museum Event” – if that counts as a work: really it’s the first iteration of a new genre (1964);

“Variations V” (1965);

“How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run” (1965);

“Place” (1966);

“Scramble” (1967);

“RainForest” (1968);

“Walkaround Time” (1968).

I’m honestly not sure of which older works you danced, but I’m pretty sure they included a 1966 BAM production of “Field Dances” (1963).

Albert Reid 1: Yes, and “Field Dances” on the ’64 tour. I understudied several dances on that tour, but I don’t remember if I actually performed them.

I performed “Summerspace”, with Merce, at Lincoln Center, and, along the way, “Septet”, “Antic Meet”, “Nocturnes”, as well as “Aeon” (sadly lost to history) on the ’64 tour. “Aeon” was a masterpiece that even Sandra Neels' famous “notes” could not help revive.

AM2. What do you remember about “Aeon”?

AR2. It had brilliant contributions by Rauschenberg in both costumes and set, as well as lights, some of which we actually wore on both wrists. There was also a scrim at the back of the stage; and when we needed to change from one side of the stage to the other, we walked, visibly of course, behind it, not dancing, just walking. There was a “doodlebug” hop and roll back on an entrance that Bill Davis and I did together. There was a combination (the thirteens?) we all did sequentially, setting off our wristlet flashbulbs (which didn’t always work) on particular counts. The phrase moved in a kind of upstage-downstage-upstage-downstage loop pattern from stage left to stage right. There were two “explosions” (puffs of smoke) upstage at the beginning of the dance which, when we performed the dance in Japan, brought up thoughts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Viola (Farber) said, “Remember us? We’re the wonderful people who brought you the atomic bomb.” At one point, a group of us entered from downstage right hopping while coiled in a fire hose. I don’t recall how that ended; I think we just hopped back offstage.

The men wore Rauschenberg’s feathered chap pant leggings.

AM3. Did you take Merce’s classes before you watched his choreography? Or vice versa?

AR3. Yes, I think the first of Merce’s dances that I saw were “Crises” (as with so many early dances, absolutely different without Merce) and “Rune”, but that was probably after I had taken some classes, although I can’t be certain. While I was dancing with Alwin Nikolais, I regularly took Merce’s Christmas and Easter (and summer?) workshops. Actually, I first saw Merce’s company (and Nikolais’) when Bill and I visited the dance festival at Connecticut College, while we were still in college, probably 1956.

AM4. We’ve all seen Cunningham revivals that fell flat without the original cast or the earlier cast. (The same applies to some revivals of some pieces by all choreographers.) Did the 21st-century “Crises”, with Rashaun Mitchell in Merce’s role, fall flat for you? Or did it work successfully as a different piece?

AR4. I never saw it with Rashaun. Bill Davis (who had run the tape for “Crises” many times on tour while he was in the company — it had tricky starts cued to precise movements, and Bill could be absolutely accurate) was invited to a rehearsal of it, with Rashaun, at Westbeth, and he said Merce’s part looked utterly different. At the end of “Crises”, when Merce stretches his waist elastic, sort of like opening his pants, toward the various women. (“Wanna play?”) Carolyn (Brown) wondered what was so funny, when the audience would laugh.

AM5. What was your previous dance experience? What if anything prepared you for Merce’s work?

AR5. I danced in a couple of musicals while at Stanford University, but had zero technique at that point. I danced in Alwin Nikolais’ company for four years, and with Murray Louis and Phyllis Lamhut prior to joining Merce, and a Judson concert with Katherine Litz. Also, Erick Hawkins “borrowed” me from Nik for some performances with his company, and he asked me to join the company, but I declined. I danced in Yvonne Rainer’s “Terrain” at Judson the year before I joined Merce. Yvonne Rainer, Bill Davis, Phyllis Lamhut and I did a joint concert at Carnegie Recital Hall at some point before I joined Merce.

AM6. What kind of ballet and/or modern training did you have?

AR6. My first modern classes were at the Lester Horton school in LA on Melrose Boulevard. Some ballet with Carmelita Maracci in LA, too. Jimmy Truitte (later an Ailey dancer and teacher) and Yvonne DeLavallade (Carmen’s sister) were two of my Horton teachers in LA.

In New York, I took ballet with an assortment of teachers early on (1959-1963), mainly Richard Thomas, and a little bit with Antony Tudor and Margaret Craske.

AM7. Do you remember any of the Judson dancers or other choreographers taking class with Merce?: Yvonne Rainer, David Gordon, Trisha Brown, Twyla Tharp? (They all did.)

AR7. Yes, I was in many classes of Merce’s with Yvonne and some with David, but I don’t remember Trisha. Trisha told me that she couldn’t do the Cunningham classes, which, I think, challenged her to move in ways that were foreign to her way of dancing, but that’s just a guess. She, David, Yvonne, Lucinda (also in many of Merce’s classes at 14th Street), and many others had to find their own way as dancers and choreographers.

Twyla and Sara Rudner took classes at the 3rd Avenue studio, but I was not in those classes, nor did I teach them. I just heard that they had been there. Some prominent Graham dancers appeared in class as well, but not for long. Also, Carolyn Carlson, a prominent Nikolais dancer.

AM8. When Merce died, Robert Greskovic wrote a piece in the “Wall Street Journal” in which, while observing the wide variety of dancers in the Cunningham company, he noted “Short-necked dancers need not apply.” You were one of the many Cunningham dancers whose neck made a vital impression. This wasn’t just because nature had given you a good neck – something in the Cunningham technique and choreography made your neck and head register. Would you like to enlarge on this?

AR8. I liked, for fun, to do neck articulations and isolations, as in East Indian dance, so maybe that made my neck stand out, but I never particularly thought of using it while dancing. I remember Deborah Jowitt, in a review, remarking on my long neck. I can see that in the mirror, while taking class, but I never thought much about it.

AM9. Merce’s work made an exceptional use of the back. Can you compare this to any of the previous teachers you had had? If you studied Graham, how did the two methods compare for you?

AR9. No, to your first question. I took classes at the Graham Studio for about two weeks early on, and found it generally too painful to endure because I didn’t have enough of the requisite flexibility, although I got better later, but not in Graham classes. Nikolais at first, but then later ballet and Merce became just right for me.

AM10. Over the decades, many Cunningham dancers needed to take ballet class (Tudor, Craske, Maggie Black, whoever) as well as Cunningham class. Did you, while you were dancing with Merce? If so, with which teacher(s)? Can you speak of how one helped the other, if it did?

AR10. I studied a lot with Maggie, Richard Thomas and Barbara Fallis while dancing with Merce and after. Later with Janet Panetta, who performed in some of my own choreography. Ballet helped give me the flexibility I sorely needed, and added to the strength I already had naturally. I studied with Tudor and Margaret Craske, but too little to make much difference. Craske spoke in a light, flute-y English accent and I missed a lot of what she said. Tudor’s combinations were beautiful and challenging but really beyond my abilities in those early days. I was never beyond the intermediate level in ballet.

I remember, years after Merce, Eliot Feld, whom I knew from Richard Thomas’s classes, came to take classes at Westbeth, and it was like a fish out of water. Muddle, muddle, muddle, grand jete, muddle, muddle. I think that I was a little more adept in ballet classes than Eliot was in Merce’s, although he didn’t stay for long.

AM11. You left the Cunningham company in 1968. Some longterm watchers of the Cunningham company – including Cunningham company dancers and/or teachers – feel that, around the time of “Torse” (1976), the use of the back in Cunningham technique and choreography grew permanently less profound and complex. (They connect this to Merce’s own increasingly limited capacity.) Your memories and/or thoughts from observing the company in later years?

AR11. What, for me, was lost were the wonderful falls that Merce devised, based on his Graham training. And, I agree, the technique became more upright as Merce’s body aged. I think Carolyn has the falls written down. They disappeared around the time we left the 14th Street studio, after the ’64 tour.

The exercise on six was there from the beginning, and remained there until the end, and it has been complex enough for me all along. Merce’s fall combinations were out of his own imagination, not like Graham’s. We once had a faculty meeting with Merce, and he wasn’t adamant about how or what we taught, but he did say that the one exercise he wanted taught in every class was the exercise on six. The arms in this exercise were forgotten along the way, although I did introduce them later in some of my advanced classes. Chris Komar asked me to teach them to him because he had never learned them.

AM12. Which aspects of Cunningham technique were hardest for you to master?

AR12. As Merce wound down in his technical abilities, the difficulty of some of his exercises and choreography wound up. I found the rapidity with which he wanted some of the foot exercises done particularly counterproductive to careful training of the body. At the 14th Street studio, in the early days, everything was difficult and challenging, but thrilling at the same time, a challenge to both body and soul. In NYC's summer heat and humidity I remember sweating so profusely then that my fingertips puckered up like they do when they’re soaking in a warm bath for a period of time.

AM13 Many Cunningham dancers found his classes as challenging for the mind as for the body. Your thoughts and memories?

AR13. Yes, that is what I loved most - the simultaneous challenges to both the mind and the body, and the most fully I’ve ever had to gather my wits and my physique together to meet them. Absolutely the greatest exhilarating moments in my dance life. Performances, of course, are fully learned and practiced, so the spur-of-the-moment learning and doing in class were, in their way, more exhilarating, and without the different kind of tension in performing. Some dancers in class were always competing with the others, something I didn’t like to do, and which I found very annoying, and which I tried not to distract from my own hard work.

AM14. I’m surprised how many people – numerous dancers, a lighting director, a production manager, an executive director, a senior administrator, some of whom have gone on to greater prestige and income – have said to me that their time with Cunningham was the most important/wonderful/valuable time of their lives or at least of their dance lives. You’re saying something close to that here: would you like to elaborate?

AR14. My experience with Merce allowed me to deepen and finesse and strengthen whatever dance gifts I potentially had. I think it was more of a fun time to be in the company because Merce was still relatively in his prime and we were a much smaller group than the one that eventually developed, from which Merce became somewhat estranged in an age-and-ability-related way. We took turns driving the Volkswagen bus, Merce wasn’t yet the acknowledged world famous genius, and we all felt that we were involved in a creative activity that was very special: a small society with a wonderful secret which we were endeavoring to reveal to the world. We were together in a convivial dance adventure.

In later years, when Merce and I would occasionally chat, I felt that he could relax back into our earlier relationship, closer in age (15 years apart) than he was with his current company, from whom he could have felt estranged in so many ways.

AM15. When you came to Cunningham, Carolyn (Brown) and Viola (Farber) had long been there too, helping to set the standard. Some dancers found them inspiring, others impossibly daunting. And some were excited that Cunningham dance theatre included both, so that even quite basic movements could be interpreted in at least two different ways – Carolyn’s and Viola’s. Merce himself was another exemplar, of course.

Can you speak of these three and their effect on you as you found your way into the repertory? Were there other Cunningham dancers who inspired or excited you?

AR15. Carolyn and Viola were so different, Carolyn so precise and Viola so approximate, Carolyn so secure in her technique and Viola more off-kilter, but both riveting, and each had a coterie of people who preferred Carolyn's way of performing or Viola’s. On the ’64 tour, in London, one of the critics referred to them as “fire and ice” (a well-known advertising term, at the time, I believe, for a brand of lipstick). Merce I loved to watch demonstrate in class in the early days, with his elegant, alive precision - you didn’t think about technique, just his unique sense of being in every moment of his dancing, the wit and intelligence of it.

Nancy Lewis took class with us, and was never/almost in the company. She was a beautiful dancer whom Merce made the mistake of not inviting in. Her dancing, I think, had a quality that was sort of a mix of Carolyn’s and Viola’s, softer than Carolyn, but at the same time very strong. When Viola taught, it was difficult to physically grasp exactly what the movement was, being a flung series of energy bursts rather than a precise, duplicatable series of positions connected by action.

In a way, Merce’s dancing is a combination of Carolyn’s and Viola’s: technique-driven (but he “never did steps”) combined with an expansive, yet agitated, lyricism.

AM16. Carolyn has often said that Merce “never did steps”. She admits, however, that she herself “did steps”. I hope you understand the distinction she is making. It seems to me that Cunningham dance theatre has always included performers of both types – those who show you pure movement, and those who draw you into the precise execution of the movement/steps. Does this makes sense to you?

If so, can you say what kind of a dancer you were when it came to steps?

AR16. Yes, I understand the distinction. I always tried to do the movement as it was shown me, but I hope that I also contributed a bit of my own soul as well. Pure technique can be so lifeless. Merce might have said that dancers are inevitably exposed as they are, but I think that some dancers prefer to remain hidden.

I tried to be alive in my dancing without, at the same time, changing the steps. I have old reviews noting the “clarity” of my dancing.

AM17. Many Cunningham dancers have spoken of his work’s musicality. Am I right to assume that, since as a rule it was not responding to music, it itself felt like music to do?

AR17. The complex rhythms give the choreography an inherent musicality. Coming from a background with considerable professional experience as a boy soprano, I easily transferred singing skills to how I performed as a dancer - the breath control to extend the length of a smoothly executed dance phrase and dynamic modulation, for instance.

Merce himself was supremely musical. He was very disappointed not to get the rights to use Satie’s “Socrate”, on which he had worked so hard. (This was after I left the company. I heard about it from Carolyn.)

AM18. But there are many kinds of musicality in dance. Was Merce’s musicality to do with rhythm, melody, more? Certainly some Cunningham dancers speak of the “song” in Merce’s work – many speak of the rhythms - and one adds “My head was full of sonatas, songs, rhythms, while I danced!”

AR18. Rhythmic variations, fluid movement execution, idiosyncratic interpolations that come from one’s unique and very personal nervous system.

Merce had his own unique punctuation, all rhythmic and legato lyricism, and very spontaneous-looking and “of the moment”.

AM19. The only extant Cunningham piece that is musically responsive is “Septet” (Satie, 1953). Does this exemplify Merce’s musicality for you? (Among those who’ve danced it, one remembers its musicality as “a bit corny”.)

AM19. Yes, “Septet”'s adherence to the music was more glued to the time signature, and could be considered “corny”. There were definite influences from Balanchine’s “Apollo” in “Septet”.

AM20. But the Cunningham dancer I’ve just quoted liked, as did others, the musicality of another Cunningham-Satie dance, “Nocturnes” (1956), which Merce kept in repertory well into the Sixties. Did you dance this?

Do you remember it and, specifically, its musicality? (A long time ago, I know!)

AR20. Yes, “Nocturnes” was more subtly musical, choreographically. I danced it in our first performance in NYC after the ’64 tour, when I was the only male dancer left in the company, other than Merce, at Hunter College Playhouse, I believe. I may have danced it after that, but I can’t remember. I remember Valda remarking on how straight my back was in my deep pliés in “Nocturnes” (when? where?).

AM21. Generally, Merce’s choreography is strikingly metric with cleanly articulated rhythms. But his later “computer” work (1993-2007) included sequences when he asked dancers to concentrate on phrasing rather than counts. To one of these dancers, he held up Billie Holiday as the model of phrasing and the way she would take a note and bend it. (Actually, he may have asked for some of this rhythmic play in earlier periods, from certain dancers, if not invoking Billie Holiday.) Did you ever know him talk this way in your era?

AR21. He may have, but I have no memories of Merce doing so.

AM22. Do you remember him talking about music and/or musicians? If so, what and whom?

AR22. My memories are of Merce talking admiringly about other dancers, such as Balasaraswati, Carmelita Maracci, Merle Marsicano, and Jean Erdman.

Everyone, including Merce, preferred that David Tudor play for “Antic Meet,” because John made lots of mistakes. Merce would mock John’s inadequacies in traditional musicianship.

AM23. I knew Merce was amazed by Balasaraswati (he probably saw her on two different visits by her to the USA). I know too little of Maracci and Marsicano, though I remember David Vaughan’s praise for the latter.

AR23. I was told that Marsicano’s way of warming up to dance was to have a long soak in a warm bath. I saw her dance and knew some of her dancers. The movement was all very subtly fluid and didn’t require much technique. I never saw Maracci dance and by the time I took class with her in LA she had had a serious auto accident and was “wired together”. Her performances were legendary and I was told that audiences would be applauding for an hour, while she bowed, left to get dressed, and intermittently bowed several more times. I took classes with Maracci in Hollywood: too crowded in a smallish space and a mix of levels from professionals (Joyce Trisler) to me, a beginner.

AM24. Merce had said to Kirstein in 1940 “I really like all kinds of dancing.” This was true. His dance enthusiasms included Astaire, Balasaraswati, Soledad Barrio (flamenco), Danilova, Fonteyn, Kathakali, Markova, Ulanova, and others. Your memories?

AR24. Also Carmelita Maracci. He raved about her performance when she came to NYC.

Fonteyn came to a party for us, I think it was at the American embassy in London; Carolyn was in heaven, two of her idols being Fonteyn and Audrey Hepburn.

Merce spent time in the 40s dancing at some ballroom in Harlem, which I’m sure you know about.

AM25. All this is separate from Cunningham’s actual music. Which composers, which musicians, and which scores do you remember best, in positive and/or negative ways?

AR25. Definitely Conlon Nancarrow’s music for “Crises", and very positively. The dance was definitely made to the music, although not in a countable way.

I loved performing the Satie dances as well, so satisfying to my body.

AM26. You say that “Crises” was definitely made to the music. Can you analyse what kind of connection it made between music and movement?

AR26. I remember hearing that Merce and John were in Mexico, where they first met Conlon Nancarrow and first heard his music. I think that Merce was enthralled by the kinetic possibilities of Nancarrow’s riveting music, and, as I understand it, took recordings of Nancarrow’s back home to make a dance. I think that, upon first hearing Nancarrow’s music Merce definitely started having specific dramatic ideas fly through his brain, if not a specific scenario. I have no idea how soon his ideas of “Crises” formed, but I believe that the unique energies that the music had were definitely related to how he choreographed the dance, and to how he thought that the dance as a whole should take shape.

I remember talking to Marilyn Wood, after a class at the Joffrey studio, about the newly made “Crises”, and asking her about it, and she said that she thought that it had to do with emotional crises.

AM27. How well did you know John Cage? One Cunningham colleague has said “You were either a Merce person or a John person. Carolyn was a John person; I was a Merce one.” I don’t accept that either/or distinction (Marianne Preger was both a Merce person and a John one, whereas she has almost no memories of Rauschenberg and Johns), but it’s true that some dancers were on John Cage’s wavelength more than others. You?

AR27. Well, I certainly worked more directly with Merce than with John, so my thoughts and recollections are more focused on him, but I would say I was both. I liked John and felt very relaxed with him, but I wouldn’t say that we ever had any serious head-to-head conversations. But, in some ways, I don’t think that he “got” dancers, or individuals: “It’s a shame that dancers have to sweat so much” or, about Carolyn and in front of Viola, “Isn’t she beautiful?"

AM28. You knew Merce in the 1960s, as well as later. John died in 1992. How did you see Merce’s relationship with John change? I don’t want to be unduly prurient about their relationship, but it certainly had its ups and downs, which I have to address. Until the 1964 world tour, very few within even the Cunningham operation realized that Merce and John were an item. That tour was when David Vaughan realized for the first time, as did others.

AR28. I always knew, or at least assumed, that Merce and John were a couple, so David Vaughan’s not knowing until the ’64 tour seems unbelievable to me. But, of course, David was ever the diplomat; or maybe I just have better intuition, better “gaydar”, than some people.

AM29. Again, can you describe the scores to which you danced - and your feelings about them? When did they actively enrich Cunningham dance theatre? Did they ever significantly detract from it?

AR29. I ignored, or blocked out, the noise scores, and danced to the Satie. “Nocturnes” and “Septet” had music that I was used to, but I accepted John’s, David Tudor’s, and the others’ scores as a new, different aesthetic that had challenges I had to meet, like in life.

In 1967, we premiered “Scramble” at the Ravinia Festival, outside of Chicago. The site was a bandshell in a park, and it was like a giant echo chamber. We hadn’t heard the sound score as yet, par for the course, and my entrance was a piqué-relevé in arabesque, into a slow plié with the arabesque moving slowly into a coupé at the ankle. I think the other dancers had equally difficult balances. The sound was horrendously loud because of the echo chamber effect. Barbara Dilley was very upset and took John to task afterward because of the high volume.

AM30. Part of the thrill of Cunningham choreography is to do with its singular way with space: multi-directional. In which pieces do you remember this being most striking in one way or another or several?

AR30. I think that the earlier dances, the ones I was in, were more conventionally oriented in general. At least I felt that way when performing in them, however they were devised. In the early Events, however, the conventional rules to do with space often changed.

AM31. Despite Merce’s always saying “Wherever you are facing, that is front”, some of his choreography seems to show a strong sense of the audience as “front”. Do you agree? If so, where do you most remember this?

AR31. In the early “Events”, we sometimes performed dances in which our “front” rotated 360 degrees in the course of the performance, which I found very difficult to do without “mad”, distracting, concentration.

AM32. At one level, Cunningham choreography, and perhaps Cunningham technique, are a profound reconfiguring of space and time. What are your best or richest memories of this?

AR32. I remember a performance, I think it was “Suite for Five” in which Merce, moving on a diagonal from upstage left to downstage right, thrust a leg and arm forward and it was, to me in the audience, as if the space (surrounded with a black traveler and black wings) was pushed, like a solid thing, in front of him. It was remarkable.

AM33. In your day, Merce’s own roles were out of bounds to other male dancers. Are there Merce roles you would have liked to try?

AR33. I have always thought that only Merce could adequately perform his own solos, and I have never had any desire to perform them myself.

AM34. Merce himself often struck people as being a remarkable actor. He also struck many of his dancers (not just Carolyn) as “knowing the story” of every piece he danced. What are your own memories of this? And what are your thoughts about it?

AR34. I agree completely. I think there was always a scenario going on in his head, at least about what he was doing and in his relation to the other dancers. The acting during his part in “Antic Meet” was amazing and had the qualities of a vaudeville routine, as in his shuffle-off-to-Buffalo solo in his white coveralls.

Also in “Crises”, in his relationship to the women, particularly Viola. No other dancer could duplicate those qualities, without being totally in his head - and body. I think that may have been what he missed when he was no longer able to dance - getting his “characters” and “thoughts” out there and out of his head and limbs.

AM35. Often with Merce it would be impossible to know, but did you sometimes feel he had begun with the scenario before choreographing it? Or do you suspect he had made the dance, probably with chance methods, and then ferreted out its scenario like an actor with a new script?

AR35. “Antic Meet” definitely had a pre-planned scenario, and I definitely think that when Merce heard Nancarrow’s music (“Crises”) that it inspired a scenario in his head.

AM36. Probably we can call all Cunningham choreography a form of drama, including such ultra-pure works as “Suite for Five”. This is not drama as character-acting; this is the drama of contrast and rigour. In general, I suspect that Merce instinctively was always thinking about dance as drama. But he was interested in many forms of theatre, from vaudeville to Artaud: the Greeks, Shakespeare, Chekhov, Mayakovsky – all interested him.

Where did you most feel Merce extended our (or your) idea of drama? (I hope this makes sense.)

AR36. See above.

AM37. Did Merce teach you any aspects of theatrical projection? (Carolyn says “No”, but in the 1990s he told some dancers “Put a friend in the house, dance for him or her.”)

AR37. I also say “No”, but his use of the arms amplified spatial projection. The only physical “suggestion” I remember Merce giving to me personally during class was a light hand on my shoulders to release a lifted tension. Of course, he made plenty of corrections while choreographing with us until we got a movement phrase right, and I remember those corrections being more Merce's physically showing something rather than giving verbal metaphors.

AM38. One of the central debates between such dancers as Carolyn and Valda (Setterfield) has been about seeking narrative or not within the movement. (Carolyn always looked for an inner narrative, Valda was content to do the movement for its own sake.) What path did you take?

AR38. I certainly had threads of narrative about “RainForest” in my head, but not much about other dances.

AM39. Carolyn, though saying and writing that Merce’s dances had (usually unknown) subject-matter, has admitted that there are some Cunningham works that were, for her, just about their own movement. Conversely, Valda, who says she did the movement for its own sake, has spoken of “Antic Meet” and “How to Kick, Pass, Fall and Run” as works that need some extra sense beyond the movement: “Antic Meet” needs something like a sense of deadpan satire while “How to Pass, Kick” needs to be “like champagne”. Any comments?

AR39. One needs a knowledge of modern dance history to know whom Merce is mocking in “Antic Meet”. The Graham is pretty obvious, but other sections not so. When I was dancing with Alwin Nikolais, Nik invited Charles Weidman to give us a workshop, which had mime elements about “picking strawberries” in it, and this was parodied in “Antic Meet” in the duet between Carolyn and Viola, where Carolyn is picking up some items (pebbles, strawberries?) and throwing them toward Viola’s head, which registers the strikes with sideward head jerks. And one of them mimed throwing a bucket of water at the other. There was a definite competition between Carolyn and Viola: which I saw starkly revealed in a facial expression exchange between them, I think during one of our performances on the ’64 tour - can’t remember where but I remember the rawly revealing moment, their ids fully on display, most particularly with Carolyn.

AM40. You came to the Cunningham company when Rauschenberg was resident. How well did you know him?

AM40. Well, we were in the same “family” for six months on the ’64 world tour, but that family had two sub-families, I think: Bob (Rauschenberg), Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton in one and the rest of us in the other. Deborah replaced Shareen Blair, who decamped mid-tour to get married, but Deborah made it clear she was joining the company only for the tour, as if she was doing Merce a big favor. I had the impression that Bob’s group felt that they were cutting edge, and Merce no longer was. I remember Alex Hay saying that we (Merce and the others in our

company ’sub-group’) were the losers, which I think probably reflected Rauschenberg’s

attitude at the time. However Alex phrased it, he definitely used the word ‘losers’ about us.

Bob was very generous and gregarious, and we all got along very well on the surface, but I never had much of a relationship with Bob, so I would never have called him a friend. He was around for the early Judson concerts, too, and Yvonne’s “Terrain”, and we had an easygoing relationship during those times.

He did a mammoth amount of work on the ’64 tour, what with lighting, building set pieces, etc.

AM41. What are your memories of Rauschenberg dance theatre when he was there helping to make it? How do you remember his chemistry with Merce, both in person and in art?

AR41. Merce was blessed to have Bob Rauschenberg as a collaborator. Bob had a strong sense of theater and of what would work on stage. The conglomerate set pieces he made on site for the performances of “Winterbranch”; the feathered Gaucho pants, firehose, cowbells (on Carolyn) costumes for “Aeon”; the scrimmed passageway we used to go from one side of the stage to the other, the white lighting, the flashbulb wristlets we wore and flashed, all also for “Aeon”; were inspired ideas of Bob’s. As was an early dance of Paul Taylor’s where Paul entered with a piece of astroturf on his back, on which lay Viola, sunbathing. And then there were Bob’s costumes for Paul’s “Three Epitaphs”.

Bob used few, or very light, or no, gels in his lighting. I think he was inspired by Florine Stettheimer’s lighting for Gertrude Stein's and Virgil Thomson’s “Four Saints in Three Acts”. Bob’s contributions to the effects of “Aeon” were probably greater than, or at least as important as, Merce’s.

As I recall, Stettheimer’s name did come up in conversation. Maybe Bob thought, big EGO that he had, that the ’64 tour was one long composition of his own, with Merce only in the mix.

I have no memory, pro-con-otherwise, of Bob’s interactions with Merce. Any artistic confabs they probably had were not ones I heard. Merce being Merce, I think he tried to avoid any contentious, face-too-face, confrontations. John did that for him.

AM42. Merce was not good with all company dancers. With some, he grew remote and formal the moment they joined the company, even if he had been friendly when they were students. Others found him painfully withholding of any kind of human connection or consideration, consistently. Most or all dancers saw he could have black moods (David Vaughan confirmed this), and some remember him as having occasional outbursts of real temper. (He apparently fired the whole company in the middle of one French tour. That didn’t last.)

What are your memories of these darker sides of Merce?

AR42. Merce could enter the dance studio and his mood would pervade the atmosphere. He could appear at an event and he would seem to have just materialized out of thin air.

How did he do that?

Merce blew up at Marilyn Wood (I wasn’t there), whose personality irritated him, as it also did Alwin Nikolais, with whom she danced before I did. Her husband later bawled Merce out, calling him a big baby.

I was in a class when Merce blew up at Shareen Blair, who also irritated him. It was as if that negative energy had been building up and burst out in class, out of all proportion to what provoked it. On the ’64 tour, we had duffle bags which were meant to hold only our dance clothes and related belongings. Shareen’s bag was packed to the gills. We had all assembled onstage with our duffle bags at the end of some performance gig, most of us with modestly filled bags, and Lew angrily dumped Shareen’s bag contents onto the stage floor and out tumbled books, “Harper’s Bazaar”, “Vogue”, and the like.

We came to rehearsal once, at the 3rd Avenue studio, and the door was locked. Merce, I presume, didn’t yet have material prepared for us. We pounded on the door for quite a long time before Merce opened it, irritated, as I recall, that we were “late”.

AM43. Did Merce write you letters? Or send you postcards? If not, do you know to whom he did?AR43. Bill and I got a card inviting us to a gathering/party after John’s death, and I still have it. The details are printed, but there is a written note from Merce which reads:

"Dear Bill and Al, It is a party for John. We thought he’d prefer it to a memorial. Please come, Merce."

I don’t recall ever getting a letter or postcard from Merce. He did invite Bill and me to dinner at Jap’s (Jasper’s) then apartment, before the ’64 tour. It was just us three - Merce, Bill, Albert - and Merce (who had the loan of Jap’s apartment) prepared the meal. I remember asparagus or green beans, but nothing more.

AM44. Which older works did you dance? “Septet”? “Suite for Five”? “Nocturnes”? “Summerspace”? “Antic Meet”? “Aeon”? “Winterbranch”?

AR45. I danced in all of the above at some point or other. We did “Nocturnes” in our first (I think) performance in NYC after the ‘64 tour, at the Hunter College Playhouse. A friend, then a Ph.D. English student at Harvard, told me that Tennessee Williams was in the audience.

There was a two-week season of modern dance given at the (then) State Theater (now, alas, Koch) in Lincoln Center and we shared a program with the Limón Company. I danced “Summerspace” with Merce then.

AM46. So interesting what you say about Tennessee Williams attending a performance. Merce and he had surprisingly parallel careers: they both arrived in New York in September 1939, and both soon were encouraged by Lincoln Kirstein.

I strongly suspect Merce's "Native Green" (1985) takes its title from a line in Nonno's Poem in Williams's "Night of the Iguana".

AR46. Wasn’t David Vaughan sending back reports on the ’64 tour that were published in the “NYTimes”? In any case, word got back about Merce’s success, particularly in London, so there was pent up curiosity when we got back, most likely prompting Tennessee Williams’ attendance at our first performance after the tour.

AM47. Did you ever see Merce using chance methods in dance composition?

AR47. No.

AM48. Now and then, Merce would speak of ways in which he had used chance. He asked the dice to choose between high, medium and low, for example. Do you remember him telling any such stories?

AR48. In “Story” we were given slips of paper for our solos, which were supposedly improvised, with directions as to facings (upstage, downstage, stage left and right), levels (high, medium, low), and such, which I found so constipating that I did in fact improvise, while considering the directions in a general way. I never kept that piece of paper.

AM49. Am I right to say that you watched Merce work in three different New York studios?: the 14th St one; the 498, Third Avenue one; and (after you stopped performing with the company) Westbeth? Can you recall the virtues and drawbacks of each? Do you or did you see the influence of any studio on Merce’s choreography of individual pieces?

AR49. The 14th Street studio was quite small, but there were windows on two sides, so there was plenty of light. The 3rd Ave. studio, although ample in size, only had windows at the 3rd Ave. end, and the walls were filthy with handprints from the dancers, which I think Merce took pride in never having painted over, perhaps as an indication of all the hard work that took place there. Westbeth was like a cathedral, with all its tall windows. It had spectacular views and much light. I remember once teaching a 4:30 class there during which (and I hadn’t been forewarned) a helicopter circled the building while a French

camera crew filmed the class for a documentary.

I didn’t have the impression that any actual studio affected a particular choreography.

AM50. We’ve been speaking of Cunningham repertory - and I have further questions about that - but there were many Events. Many of these were in unconventional non-theatrical locations; and almost all of them placed known dances in new aural and design contexts. Can you speak of how you felt about Events? Some dancers liked them least, some loved them especially.

AR50. Well, I found them a bit confusing because of the re-orientation of the movement sequences with which my body was very familiar which were always being thrown into a new kinetic lineup with which I was unfamiliar. Then there was the time, in Sweden I think, when “front” made a 360-degree rotation in the course of the dance. I never felt that I could physically commit to the performance of the dance as much as I was able to in a more conventional rendition. Extremely challenging mentally, but I tried. More rehearsal of each new situation would have helped me, I think.

Also, thinking aesthetically and philosophically, you have a dance that was thought out, presumably, to be a complete and coherent whole, with all its effects and nuances intact, and then you chop it up into pieces to make another dance: that didn’t appeal to me because it’s as if you’re saying that the completeness off what you originally made and its particular sequence of movements didn’t really matter, or didn’t add up to what you meant in the first place.

AM51. Solos and soloism are pretty near the core of Cunningham dance theatre. What solos did Merce make for you? And what other solos did you inherit?

AR52. I had a solo in “Variations V”, but it happened in the midst of other activity, so I don’t know if you can call it a solo. And there was one in “RainForest”, but, again, I wasn’t alone on stage.

I taught them both in LA for the “Night of 100 Solos” (2019). I can’t recall other solos, although there might have been some short ones here and there. There was a solo, I think it was in “Variations V”, which I performed and that was later in the dance picked up by other dancers. I remember Carolyn saying “Oh, he’s given you a solo”, but, when we came to perform the dance Merce was in the back, jumping around and upstaging me. I think it was at the former Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center, which is now the David Geffen Hall, the one that’s getting a big acoustical renovation.

AM53. And can you talk about soloism in Cunningham? Where does it take you in mind and body?

AR53. Well, if you’re the main focus of attention, it certainly clarifies your thinking into getting everything you’re doing exactly right and projecting it in an amplified, but careful, way toward the audience. One also felt expected to give it some extra performing oomph.

AM54. Merce spoke of dance as “a spiritual adventure in time and space”. Can you speak about this in your own experience?

AR54. Hoping not to be precious, I did always think of dance (the daily taking of class with other “novitiates”, the presenting of a work of art to an audience of enthusiasts) as a religious devotion, something I never felt during my Presbyterian/Episcopalian upbringing, although my parents, many thanks Mom and Dad, were not seriously religious and preferred reading the Sunday paper to going to church. However, I was boy soprano soloist at St. Paul’s Cathedral, the head of the Episcopalian diocese in Los Angeles, and I did love the music and the singing of it.

AM55. Rauschenberg left the Cunningham company at the end of the 1964 world tour. In 1967, Jasper Johns joined the Cunningham enterprise as artistic advisor, inviting a range of other artists to design individual dances and sometimes designing dance himself. Johns was and is a very different character from Rauschenberg. How well have you ever known him?

AR55. Very little. Mainly cutting the holes in the “RainForest” costumes with scissors (it’s in the Pennebaker documentary). Jap wasn’t a theater person like Bob. He did elegant color schemes, mainly shades of the same color. I knew Jap in a social sense only: at his then studio in an old bank building in SoHo (Andy Warhol, etc.); and at a party at Henry Geldzahler’s apartment - where I witnessed Salvador Dali, having acquired the arm of a pretty young woman, walking back and forth in the living room, ignoring everyone else.

AM56. The chemistry between Jasper and Merce interests me. One Cunningham colleague has described Jasper as “always a soothing presence” for Merce, whereas another, remembering Jasper’s sparing use of words as something being occasionally frightening, added “I think even Merce was sometimes scared of Jasper”. Your thoughts and memories?

AR56. I think that Merce admired Jap very much. He once commented to me how smart he thought Jap was — in dealing with the “art world”, “rich patrons”, etc. Jap did have a calm, quiet manner, although I don’t think that he was shy. We talked at gatherings, but nothing memorable for me. And “frightening” -- I don’t think so, but perhaps his eminence frightens some people.

AM57. Do you have particular memories of “Scramble”, its creation or performances? Have you seen it danced since you were in it? Parts of it often returned in Events.

AR57. I haven’t seen “Scramble” performed since I was in it, and I have no memories of its creation, other than the difficulty of dealing with the set pieces of Stella’s decor, and its first performance at the Ravinia Festival, which I’ve described above (AR29).

AM58. Many Cunningham dancers have remembered that, when Merce was preparing a new work, his classes became something of a laboratory. Sometimes they could tell he was brewing new choreographic ideas by the way he taught; sometimes they only later realised that he had been preparing them for his next creation. Do you have any specific memories of this?

AR58. I think that Merce worked out most of his choreographic ideas in class, but I can’t say that I was aware in any particular class that he was doing so.

AM59. How singular a work was “RainForest” (1968) within the Cunningham repertory you knew? (Valda remembers your standing in the wings after dancing in this and saying something like “Albert, you danced that wonderfully tonight.”)

AR59. It definitely seemed an unusually dramatic work, and unlike Merce’s other work. I think Merce was mulling over, at that point, potential future possibilities for me as a dancer in his company. I don’t recall Valda saying that about “RainForest”, but I do remember her commenting how straight my spine was in a deep pliè during “Nocturnes”, and now I’m having to correct a mild mid-back scoliosis, which I don’t think I had earlier. (P.S. The scoliosis has been fixed by my current chiropractor - she is blind, by the way - and confirmed this past week by my Trager practitioner - November, 2020 - as perfectly straight. How my back feels is another matter.)

AM60. Do you remember how Merce made “RainForest” (1968) and how he gave you the choreography? Did he focus entirely on counts, spacing, movement? It is, to us, such a dramatic piece: did he intimate that in any way?

AR60. The dance was made at the 3rd Avenue loft studio. As was his usual wont, Merce didn't say anything about the piece, but we sensed the drama of it, and I particularly remember Carolyn working to break through her reserved elegance into a wildness of movement. Merce showed me my movement and the predatory stealth in my entrance movement, but didn't say anything about any dramatic qualities he might have had in mind.

I think that he assumed that what he wanted was in the movement itself, and he was very specific about how he wanted that performed, with its pelvic bumps. I don't remember counts being important, but rather spatial relationships and length of phrases. Merce showed the movement, and I followed. I can’t recall any spoken metaphoric nuances.

AM61. How well did you know David Tudor? Can you describe him? How much weight did he carry in the Cunningham operation?

AR61. David was much respected by all of us, including Merce. We were all glad when he (rarely) played for class. He and I sometimes roomed together on tour, during which times I tried to appreciate his eating habits, which leaned toward very spicy hot — he loved eating in India, and recommended restaurants to us when we were in New Delhi on the ’64 tour, the Moti Mahal being one.

If John played the piano for “Antic Meet” (many mistakes, wrong keys depressed), there was much groaning. When David played (classically trained, musical), there was relief. Merce would laughingly mock John for his deficits in playing “regular” music.

AM62. “RainForest” was Tudor’s first Cunningham composition. Did this create a change in him?

AR62. I don’t think so. He seemed to me to remain the same quiet, but friendly, David, seriously busy with the technical/musical demands of his work.

AM63. Subsequent generations of Cunningham dancers came to recognise that, if Merce chose Tudor as his composer for his next piece, he intended it to be one of his “dramas”. You danced to the first Tudor composition, but you already knew him. Was there anything in this quiet, friendly man that you now see contained these often dark dramas?

AR63. Only his taste for extremely hotly spiced food. When I roomed with him, he would pull out these various containers with spices to be added to whatever he ate, and he knew the best restaurants when we toured India.

Nothing in his manner, or in his behavior, would indicate dramatic elements in his personality or character.

AM64. How late in preparation did you know you would be dealing with the Warhol pillows?

AR64. I think we knew the Warhol pillows were going to be there, but I don't remember rehearsing with them, although I could be wrong. My memory is that, like the music, we first encountered them in performance. I remember that, during the performance at BAM, one of the pillows drifted off the stage into the audience and Jap, seated near the front, got up and batted it back onto the stage.

AM65. Do you remember in performance how much those pillows varied and affected the dancing? and can you say anything about this?

AR65. In performance, the pillows drifted about a lot and we were allowed to kick them out of our way if they interfered with our movement. We danced despite their being there and what happened happened. They were so light that they weren't any real impediment.

AM66. Do you remember Jasper Johns’s work on the costumes? And, again, what can you say about it? (And did you hear that Warhol's idea was that the dancers should be naked?)

AR66. Yes, we knew that Warhol wanted us to dance naked, but Merce would have none of it. Jap (Jasper) cut holes in our costumes while we were wearing them. We were in some costume room area, I can't remember where it was exactly, but I remember there were windows and bright sunlight.

He used a large pair of scissors and was very careful. The costumes were dyed a light beige, much like the photo in the Times when MCDC (Merce Cunningham Dance Company) revived the dance. I don't know if Jap actually dyed the costumes himself. But he decided on the flesh tone colors.

AM67. We now know that Merce was influenced in “RainForest” by having read the anthropologist Colin Turnbull's "The Forest People". How early on did you hear this, if ever?

AR67. This is the first I've heard of Colin Turnbull's "The Forest People", but others may have.

AM68. We also know that he told David Tudor about his idea of a forest, and Tudor said "Right, I'll try to get the sound of rain on leaves". Did you hear that at any time?

AR68. I wasn't privy to any conversations Merce might have had with David Tudor or Jap regarding the costumes and the music. We knew that David was after forest sounds.

AM69. Some Cunningham dancers needed to make dramas, stories, while they performed Cunningham choreography. This piece perhaps lends itself more to ideas of characterization and drama more than most Cunningham pieces. Did you feel you were part of a drama? Did you have any idea of your character or story?

AR69. It would have been difficult not to feel some drama in “RainForest”, just from the movement we were given. I had this in my head: Merce was in his “kingdom” with Barbara in his realm/possession. I was an interloper, challenging him in some way and took over with Barbara as Merce left the scene. Gus came on later, a second interloper, but that's as far as my “story” goes. I think there was more prominence given to other male dancers in the company than Merce had given before, such as in my brief Tarzan duet with Carolyn.

Just prior to our performance in Chicago, I fell on stairs carrying groceries up to my 5th floor apartment in NYC and tore some intercostal cartilage, perhaps even cracked a rib. So performing that skittering movement on my forearms with Barbara on my back was absolute agony, even though I was wearing a rib corset I got from a doctor I saw in Chicago -- but I did it.

AM70. One particular form of drama in Merce’s work occurs in the great male-female duets he made. Can you talk about your experience and/or observation of these?

AR70. No, other than “RainForest”, and I did enjoy my duets with Barbara and Carolyn in that dance, although they were brief.

AM71. You’ve touched on the characterisations and stories in “RainForest”. At the end of that work, Merce (or his role) returns to the stage with a completely different energy from the way he behaved in the opening. Sometimes I think it’s the same “character” but now galvanised, even enlightened and/or angry/driven. Sometimes I think this is a whole different “character”. Any thoughts or comments on this?

AR71. I think Merce may have been considering a future transition in his performances from that of the primary soloist to that of a more shared performance experience, to a less dominant role in his company, as a possibility, but JUST a possibility.

AM72. One of the works in which Merce was surely extending everybody’s idea of drama was “Walkaround Time,” made the same year (1968). What are your memories of this?

AR72. We didn’t perform it much, and Jap’s plastic deconstructions of Duchamp’s “The Big Glass” were an impediment to the stage space. I don’t remember it being particularly dramatic, but then I can’t remember anything we did.

AM73. I mean that its drama lay in that very objectivity – its moves were just its moves. Very Duchamp. But Carolyn rising a leg slowly from relevé fourth, Merce running on the spot while changing his tights: these were greatly dramatic happenings even though nothing happened.

AR73. I just have no memory of what I did in that dance, or what others did.

AM74. “RainForest” and “Walkaround Time” were and are highly unalike pieces – “RainForest” has such much animal wildness and quasi-narrative drama and characterisation, “Walkaround Time” is such a work of formal experimentation - yet Merce prepared them at the same time: on successive nights in 1968 (March 9 and March 10). Sometimes his notes for them occur on the same page of his notebooks, sometimes it’s hard to know at first which dance he’s preparing on paper. I may be wrong – for several works, some of Merce’s notes seem to be missing – but I infer that “RainForest” was one of his most intuitively made works, whereas “Walkaround Time” was very deliberately prepared before rehearsals. Do you remember him making them at the same time? And were you struck by their dissimilarity?

AR74. Well, we rehearsed them at the same time and, while I remember specifics about the rehearsals for “RainForest” and the dramatic qualities of the dancing, I have no memories of rehearsals for “Walkaround Time”.

AM75. “Walkaround Time” is a work about Marcel Duchamp’s work. Did Merce speak about Duchamp either there or in other contexts?

AR75. Well, Merce and John were friends with Duchamp and his wife, so their names would come up in conversation. John and Marcel played chess together, I believe. Duchamp took a bow with us after the first performance of “Walkaround Time”, and it premiered the night after our first performance of “RainForest”.

AM76. Are there roles of yours you’d like to coach or to give suggestions for? Marianne Preger, in her 2019 Cunningham memoir, remembers that she spoke to a 1999 Cunningham dancer who was dancing the role that she, Marianne, had created in “Suite for Five”. She, over forty years after leaving the company, was able to say how one step had felt to do, in a way that helped the younger dancer. You?

AR76. Maybe a dance quality, like the wildness in “RainForest”, but not a specific step, except perhaps by being reminded by a record of my dancing, as I did for “Night of 100 Solos”.

AM77. When you left the company, I presume you taught your roles to your successor. Yes? This apart, have you ever taught any of your roles to younger dancers?

AR77. I remember teaching my role in “Septet” to Niklas Ek, Birgit Cullberg’s son, and later my several roles to Chase Robinson and Mel Wong, just before leaving the company, but I have never since taught any of my roles to dancers. And, I must say that I have a terrible memory, even for roles that I very much enjoyed dancing.

AM78. Did Merce ever allow you to see the preparatory notes he made on a piece?

AR78. No.

AM79. Merce was also a master of secrets. (He taught himself Russian while touring with the company - and years later wrote to Baryshnikov in perfect Cyrillic script.) What other secrets about Merce took you by surprise when you discovered them?

AR79. His ability to appear, suddenly, seemingly out of thin air, as if by a magic wand. His ability to appear to move whole blocks of stage space with his arms and legs. His ability to draw fairly well.

AM80. Merce’s effect on women was something. Marianne Preger Simon’s book describes the powerful feeling she had on the one occasion they shared a hotel room. Valda once told me that the experience of being partnered by Merce had an intensity comparable to a profound sexual experience. I have sometimes thought of Merce as a “closet heterosexual”, which makes sense to some of the women who knew him. Your thoughts?

AR80. I would say that Merce was pretty solidly homosexual, although I don’t deny that many women were attracted to him. I remember an occasion when a group of us in the company was talking with Merce, and when he left the confab, Viola saying, with deep feeling, “How I love that man!"

AM81. In the 1970s, Merce began to make an increasing issue of his seniority or age or even incapacity. In the 1980s and 1990s, that became yet more pronounced. Some found it very hard to take to watch Merce grow old in public. Your memories and thoughts?

AR81. I loved the solo I saw at City Center where Merce sat in a chair, wearing a grey suit as I recall, using his torso and arms only, but to great, and moving, effect.

Otherwise it was painful to see him walking on those crippled feet. But, unlike Martha Graham, he seemed perfectly aware of infirmities, and dealt with them as best he could. Movement while aging was just another interesting challenge for him, I think, as it is for me now, although I think that my feet are in somewhat better shape.

Did I mention anywhere that once, when I was in the company and Merce and I were talking about what parts of the body were bothered most by laying off for a while, he mentioned that in his early days, in order to try to give his feet a better arch, he would press the tops of his feet against the tub while taking a hot bath. I can just imagine with what determinatiion and force he might have done that. He also said that his calf muscles were most affected after a lay-off.

AM82. Also in the 1970s, the dancing of Robert Kovich and Chris Komar began to raise the bar for Cunningham allegro technique. Robert Swinston has long said that he was never able to get the dancers of the 1990s and 2000s to equal the speed of the original cast performances of “Soundddance” (1975) and parts of “Torse” (1976). Did you observe the dancing of these two (both long dead, alas)?

AR82. Yes, both excellent dancers, although a bit dry to me. As Merce declined physically, his technical demands on his dancers increased exponentially and many rose to the challenge, but I found the demands a bit cruel and the results more soulless than in his earlier work. Chris had been in a ballet company prior to Merce, which could account for his allegro abilities. I remember noting Chris’s appearance in class in a conversation with Carolyn and Merce, and as potential company material.

AM83. It is astonishing how often Merce’s work contains doubleness of one kind or another: two different things going on at the same time, two layers of objective purity and/or actorly drama, two separate realms, punning titles. Any comment?

AR83. When Merce performed there was always, I think, what was going on in his head (the actorly drama) as it informed his dancing. This was particularly true in his early works.

In works like “Antic Meet” it was obvious to everyone - the humor, the satire - but in his later works, not so, and he didn’t let on to the other dancers what was going on in his mind. Just do the steps.

AM84. Merce certainly loved to grumble about having to teach. He was nonetheless one of the great teachers, and remarkably inventive: people were electrified by what his classes did to their brains as well as their bodies. What are your memories of Merce himself as a teacher? And what are your memories of (your thoughts about) his reluctance to teach?

AR84. Yes, he would say that he disliked teaching, but that he realized that it was necessary to preparing a company for his work. We never had class on the ’64 tour, but were left to our own devices. We did, however, give a couple of demonstration classes along the way, one, I think, in London, at the Phoenix Theater I believe, and one in Paris.

Merce’s classes were, indeed, electrifying, and his demonstrations of the exercises were fascinating to watch (the energy in his legs, his hands alive, fingers twitching, his spine so articulate). I remember Chris Komar remarking with amazement about how Merce could keep coming up with new, remarkable movement combinations, even in his old age.

I remember, at the 14th Street Studio, above The Living Theater, Merce coming out of his small, private room at the side of the studio, shuffling off his footwear, formally walking to the center of the studio, and commencing the class, like a solemn, but vivid, ritual.

AM85. You taught Cunningham technique. When did you start? For how long did you do so? Please tell all.

AR85. I was the first person, so far as I know, other than Merce, Carolyn, and Viola, to teach technique at the studio (14th Street). Merce asked me one day if I could teach the Saturday class. Overwhelmed, I prepared mightily. The students who came, many my peers, had, I think, their noses put a bit out of joint. The class went fairly well, and I subsequently continued teaching, for about 36 years. I was still performing with the company at the time, so I think it was about 1966. After I got my job at Bard College, getting paid real money, I would often, after teaching at Bard on Monday and Tuesday, rush back to teach a 4:30 Tuesday class at Westbeth. I loved it.

AM86. It's possible that Margaret Jenkins (and June Finch) began to teach Cunningham technique at the studio before you, when the company was on tour In 1985, with Merce’s approval.

AR86. Funny, I don’t remember Margie Jenkins being at the 14th St. Studio, which is where I began to teach, but I could be wrong. I remember her most for teaching at the 3rd Avenue studio and at Westbeth. It was she who did so much to save and repair Merce’s things when there was a flood of his upstairs aerie at 3rd Avenue. She and Merce were very close and her knowledge of Labanotation was a great help to him.

I don’t have a record of the exact date I began teaching for Merce, but I know it was at the 14th Street studio, and on a Saturday. Maybe David Vaughan’s studio records would have the date.

AM87. Merce invited you to the wake for John Cage in 1992. Did you attend?

AR87. Yes, I did attend the party for John at the studio after he died. It was amazing for me in that there were generations of Cunningham-affiliated people, dancers, musicians, and otherwise, who came. People I hadn’t seen in decades, some having come from quite a distance. It was like the ball at the end of Proust.

AM88. When you go to watch Cunningham dances, I presume memories are strong. But you watched the company and Merce’s choreography evolve over more than forty years after your departure, with some very remarkable dances and new creations. Other than memories, what feelings have you had? After watching Cunningham choreography for more than forty years, I’m still understanding aspects of it better. You?

AR88. I haven’t always liked some of Merce’s later works, although my muscles twitch, sitting there in the audience.

It was nice to see other dancers and how they improved doing his works. I didn’t miss being up there dancing; the joy in my body wasn’t as strong as it once was in performing, unlike Merce.

AM89. For some dancers and some devotees, Cunningham dance fulfilled sides of themselves that otherwise or also sought out alternative philosophies or politics. For others, it introduced them to new insights into the spiritual life. Most Cunningham dancers were intelligent, and the teaching and choreography stimulated this.

Your feelings about this Cunningham connection to brain and spirit?

AR89. Mighty challenges to my body and brain, and a generous amplification of my spirit. I felt more at home in that intelligent and stimulating community than I ever did during my five years at university, although I did enjoy those years as well, and they had their own special fruit to bear.

Being in the dance world, and especially in Merce’s part of it, felt like being home at last, at least spiritually. My home life, growing up, was very nurturing and pleasant, and I’m really grateful for the loving parents I got, but one changes and expands out in the big world.

--

@Alastair Macaulay, 2021

1: Albert Reid, seen on the documentary film “If the Dancer Dances” (2019)

2: Merce Cunningham (left); Albert Reid (Center); Gus Solomons Jr (right). Screen-capture from the documentary film “498, Third Avenue”.

3, 4: These blurry photographs of Albert Reid in Cunningham’s “RainForest” (1968) is a screen-capture from the film of that work’s premiere.

5. Merce Cunningham, “Walkaround Time” (1968). Albert Reid is in the foreground on the left, Cunningham in the foreground on the right.

7: Albert Reid at a 2019 California celebration of his career

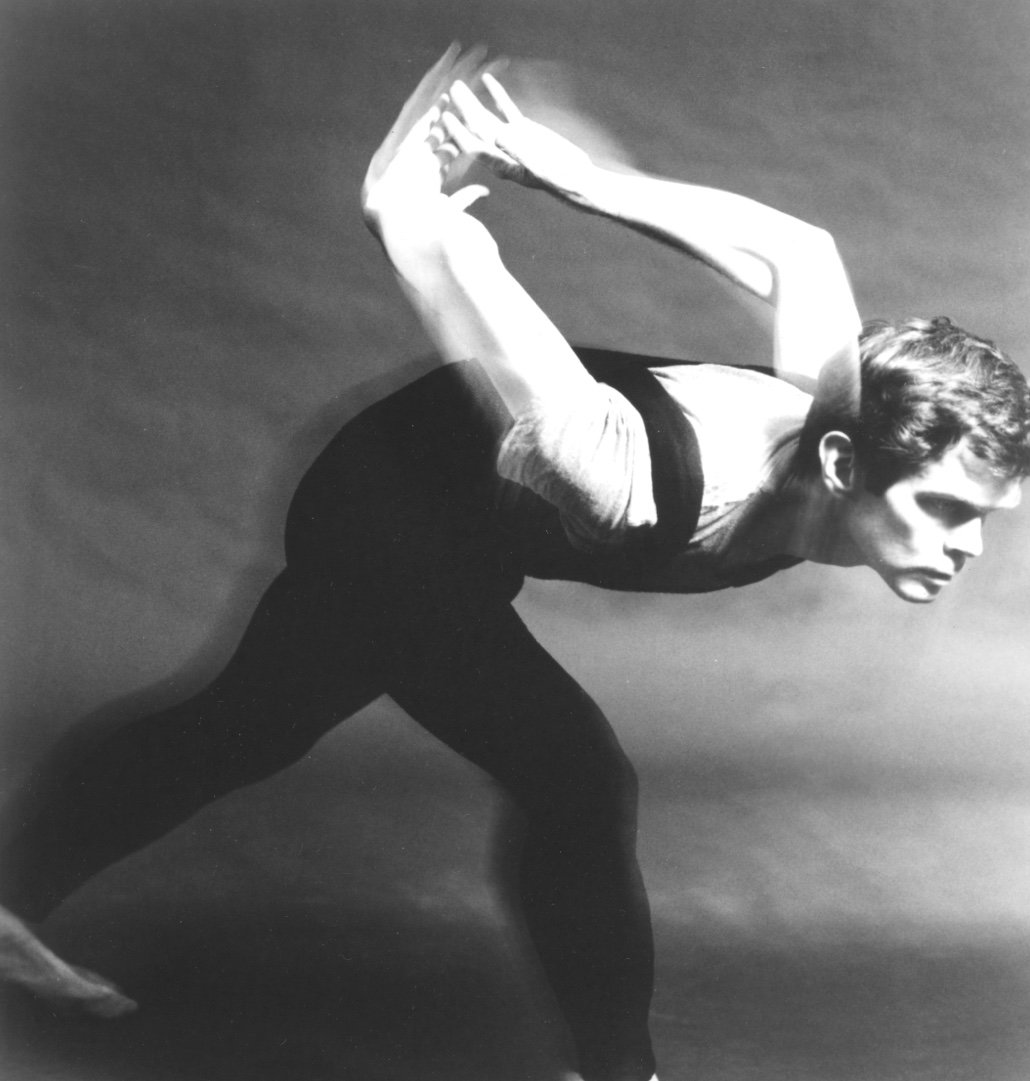

8: Albert Reid

9: Albert Reid

10: Albert Reid

11: Albert Reid