Memories of Lynn Seymour in her 1977-1978 season

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. The premiere of Kenneth MacMillan’s “Mayerling” (Valentine’s Day, 1978) happened halfway through what was Lynn Seymour’s final full season as a member of the Royal Ballet, and which - though she only decided to leave the company around April, to become director of the Munich Bayerische Staatsballett - was very probably the most astonishing year of her always astonishing career. In October-November 1977, she was the original Carabosse of Ninette de Valois’s new production “The Sleeping Beauty” and (with Rudolf Nureyev) its fifth-cast Aurora; her second Aurora of the season was the most revelatory performance of any nineteenth-century role I had ever seen. In November, she also danced a triple bill in which there were two performances when she performed all three ballets, opening with Glen Tetley’s “Voluntaries”; the central ballet was “The Invitation”, in which she and David Wall not only danced the roles of the Young Girl (which she had created in 1961) and Young Man but also, in another cast, the Wife and the Husband. (The third ballet, I believe, was Jerome Robbins’s “The Concert”, where her qualities of rapturous fantasy and comic timing remain branded on memory for many of us.) Between October 1977 and February 1978, she also danced multiple performances of Natalia Petrovna, the role she had created in Frederick Ashton’s “A Month in the Country” (1976), an interpretation that had already become legendary since the ballet’s premiere.

She gave guest appearances with the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet in which she newly illumined the mazurka and pas de deux of Fokine’s “Les Sylphides” and the can-can of “La Boutique fantasque”. At one charity gala at Sadler’s Wells, she was reunited with her 1960s partner Christopher Gable to danced the final pas de deux of Ashton’s “The Two Pigeons”. She also joined Nureyev in Paris to dance the title role of “La Sylphide”.

And after creating Mary Vetsera in “Mayerling” in February 1978, she - now thirty-nine years old - danced the heroines of three other MacMillan three-act ballets: Juliet in “Romeo and Juliet” (which she had created in 1965, albeit without dancing the premiere), Anastasia in “Anastasia” (which she had created in 1971), and Manon in “Manon” (1974), a fifth-cast interpretation where those who had admired the earlier performances of Antoinette Sibley, Merle Park, Jennifer Penney, and Natalia Makarova admitted that Seymour took the character through a larger arc, seemed to belong to the eighteenth-century paintings, and made the role more about Manon’s decisions (rather than her vapid passivity) than anyone before or since. (The sexuality she showed in the first bedroom pas de deux was astounding, her arms writhing. At the end of the bracelet pas de deux, it was she, not des Grieux, who made up her mind to remove the bracelet, though not without strain. The passionate delirium with which she danced the final pas de deux was incandescent.)

She said at this time that her three favourite roles were Juliet, Anastasia, and Natalia Petrovna. In all three, she exemplified her understanding of how to take a role on a huge dramatic arc. No Juliet has ever been less sexual or gauche in her first encounter with Paris; but with Romeo she discovered not only sensuality but temper. No victim she. The whole ballet became about Juliet’s willpower. To this day, I have never seen a dancer trace a larger journey than she did as Anastasia: in each act, it was hard to believe that this was the same woman we had seen before, as her whole weight and body language changed from childhood adolescence to debutante discovery to traumatised maturity.

Finally, in a July in which she played Carabosse in a special performance for Ninette de Valois’s eightieth birthday, she returned to another Ashton creation, “Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan” (1975-1976), in which, barefoot, she struck a different note in each waltz. Her slow, walking entry for the fifth waltz, only gradually revealing that her hands, placed tenderly over her solar plexus, held rose petals, which she then, enchantingly, released. (After Ashton’s death, she devised an alternative version, whereby Isadora, remaining onstage, artfully discovered the rose petals under the onstage piano. A mistake: Ashton knew what he was doing.) It’s hard to explain how that simple entrance seemed the most holy thing I ever witnessed in a theatre, but I testify that it felt so.

The curves of her legs and feet were always famous (her feet are the only feet in dance I have wanted to take in my hands and kiss), but the curvaceous plasticity of her back, arms, hands, and upper body was all of a piece, so that everything about her dancing seemed unified. As for her acting, the most legendary part of her legend, it often shocked her audiences. On the balcony in “Romeo”, she writhed like a cat on heat, pressing her arms and back for maximum friction against the pillars. (“That was my Judi Dench rip-off,” she told me; “I loved that RSC 1960 Zeffirelli ‘Romeo and Juliet’!” When I told Judi Dench, she in turn described Seymour as “one of my heroines.”) Some ballet regulars recoiled: “That’s not Juliet, that’s a whore!” The Royal Ballet subsequently removed the pillars, as if to ensure no Juliet could ever try to duplicate the effect.

In summer 1978, in a Royal Festival Hall fortnight nicknamed “Star Wars”, she danced “Les Sylphides” with Margot Fonteyn, Natalia Makarova, and Ivan Nagy; the Ashton “Sleeping Beauty” Awakening pas de deux with Stephen Jefferies; and Bournonville’s “Flower Festival at Genzano” pas de deux with Fernando Bujones (nobody has ever danced one demi-fouetté pivot and re-pivot with her aplomb and musicality). At the start of the 1978-1979, Seymour danced Mary Vetsera and Natalia Petrovna (conducted by the great Robert Irving), and acted Carabosse, before departing to take up directorial duties in Munich. She returned to dance in London a number of times over the next twenty years, in choreography by Ashton (the Tango in “Façade”), John Cranko (“Onegin”), MacMillan (the one-act “Anastasia”), William Forsythe, Ian Spjnk, and Matthew Bourne (reinterpreting the Queen in his “Swan Lake” and creating the Stepmother in his “Cinderella”.

Before the 1977-1978 season, I had already seen her dance many roles, including Giselle, the “Corsaire” pas de deux, Odette-Odile, “Raymonda Act III”, and Balanchine’s Terpsichore , all with Nureyev, one of her most valued and devoted friends in dance. I remember her as Cranko’s Shrew, in van Manen’s “Twilight”, in MacMIllan’s “Concerto”. I had already loved her Juliet with Nureyev and Baryshnikov; and had missed very few of her frequent performances of Natalia Petrovna, a role I eventually saw her dance twenty times. But the memories of her 1977-1978 season form a climax to my infatuation with her. Quite probably she is the main reason I became a critic; I needed to write letters to friends to describe and explain the many amazements of her successive performances. Watching “Mayerling” this week and suddenly remembering how she danced those four three-act MacMillan ballets in the six months of February-July 1978, I’m overwhelmed once more. Dance happens twice over for audiences: the experience as we watch and then the revelation that we keep trying to comprehend in successive hours and months and decades. I’m still adding up the meanings and ideas within Seymour’s performances - and I am forever in her debt.

Saturday 8 October

1: Lynn Seymour as Aurora in Act III of “The Sleeping Beauty” as filmed in November 1977 for Margot Fonteyn’s TV series “The Magic of Dance”.

2: Lynn Seymour as Juliet with David Wall as Romeo in Kenneth MacMIllan’s “Romeo and Juliet”. Photo: Leslie Spatt.

3: Lynn Seymour in Act One of Kenneth MacMIllan’s “Anastasia” (1971). Photo: Anthony Crickmay.

4: Lynn Seymour as Manon in Act Three of Kenneth MacMIllan’s “Manon”. Photograph: Anthony Crickmay.

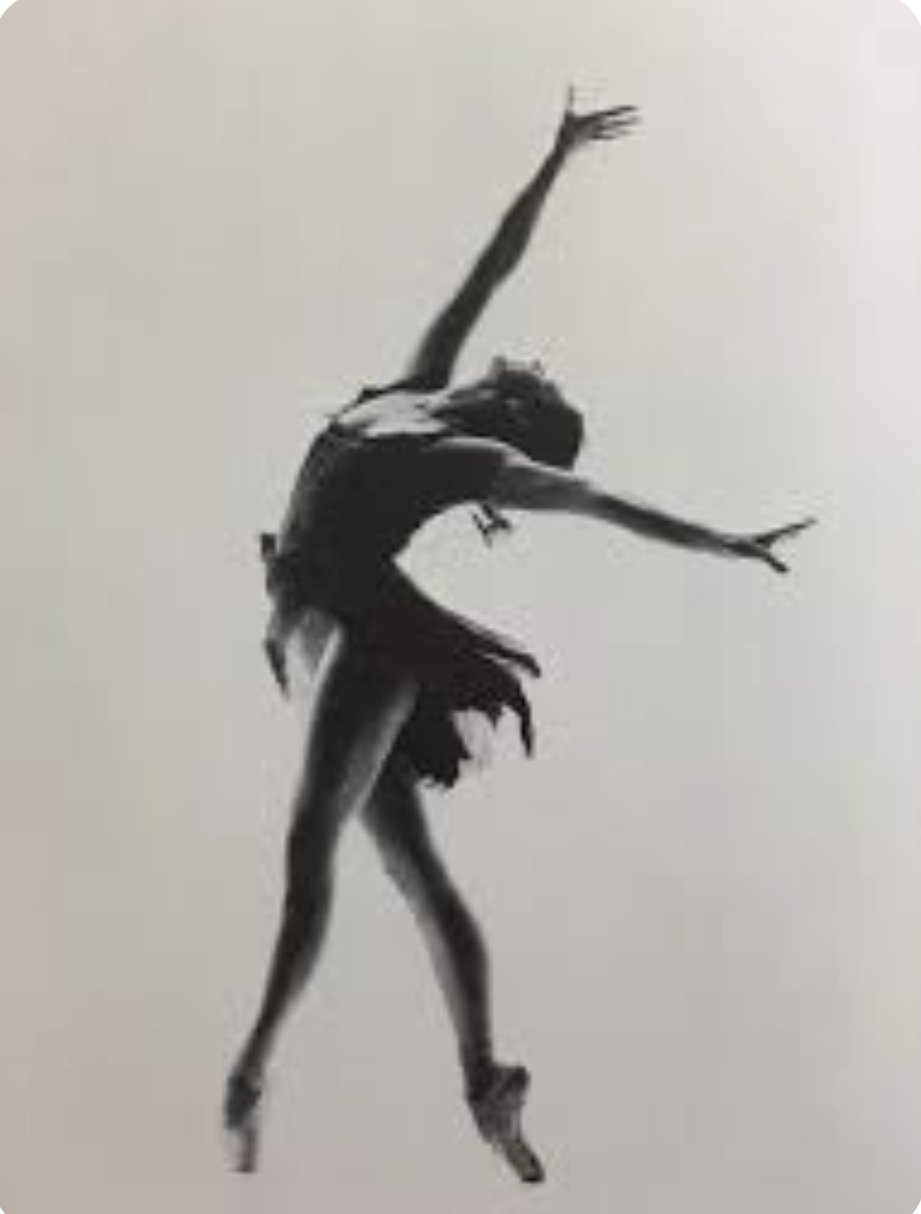

5: Lynn Seymour in Frederick Ashton’s “Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan” (1975-1976).

6: Lynn Seymour as Natalia Petrovna in Frederick Ashton’s “A Month in the Country” (1976).

7. Lynn Seymour and David Wall in the final pas de deux of Kenneth MacMIllan’s “Mayerling”

8: Lynn Seymour and David Wall in the final pas de deux of Kenneth MacMIllan’s “Mayerling”

9: Lynn Seymour and David Wall in the final pas de deux of Kenneth MacMIllan’s “Mayerling”