Carolyn Brown, partner and historian of Merce Cunningham: Women’s History Month in Dance, 2021

Women’s History Month in Dance 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106. From the beginning of his professional choreographic career, Merce Cunningham began to choreograph for women as well as for himself. His first choreographic concert, in 1942, was a collaboration with his friend (and fellow Martha Graham dancer) Jean Erdman: they shared a programme of duets and solos. In 1947-1949, he made three pieces in which his partner was the teenage ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq, whose intelligence, style, versatility, wit, and long-limbed physique made her a fascinating counterpart to him. (In his old age, he would always laugh to recall how, when he asked her what kind of movement she liked, she replied “Very fast or very slow.” Generations of Cunningham dancers have felt that that phrase summed up the essential contrast of tempo in Cunningham choreography, though he actually often composed in-between speeds too.)

When he officially formed his company in 1953, he had just found the female partner he knew complemented his own presence best: Carolyn Brown, seen in these photographs. (He had also found Viola Farber, in some ways a more kindred spirit to himself but whom he less often featured as his partner. Farber was a naturally conflicted dancer, who could combine opposite impulses at the same time and who brought an element of wildness to Cunningham classicism. The striking differences between those two women were to enrich Cunningham dance theatre for all who saw it: here was evidently an idiom that gave room for both these two throughly unalike movers and personalities to co-exist. Brown danced with him until 1972; Farber until 1965, with a return season in 1970.)

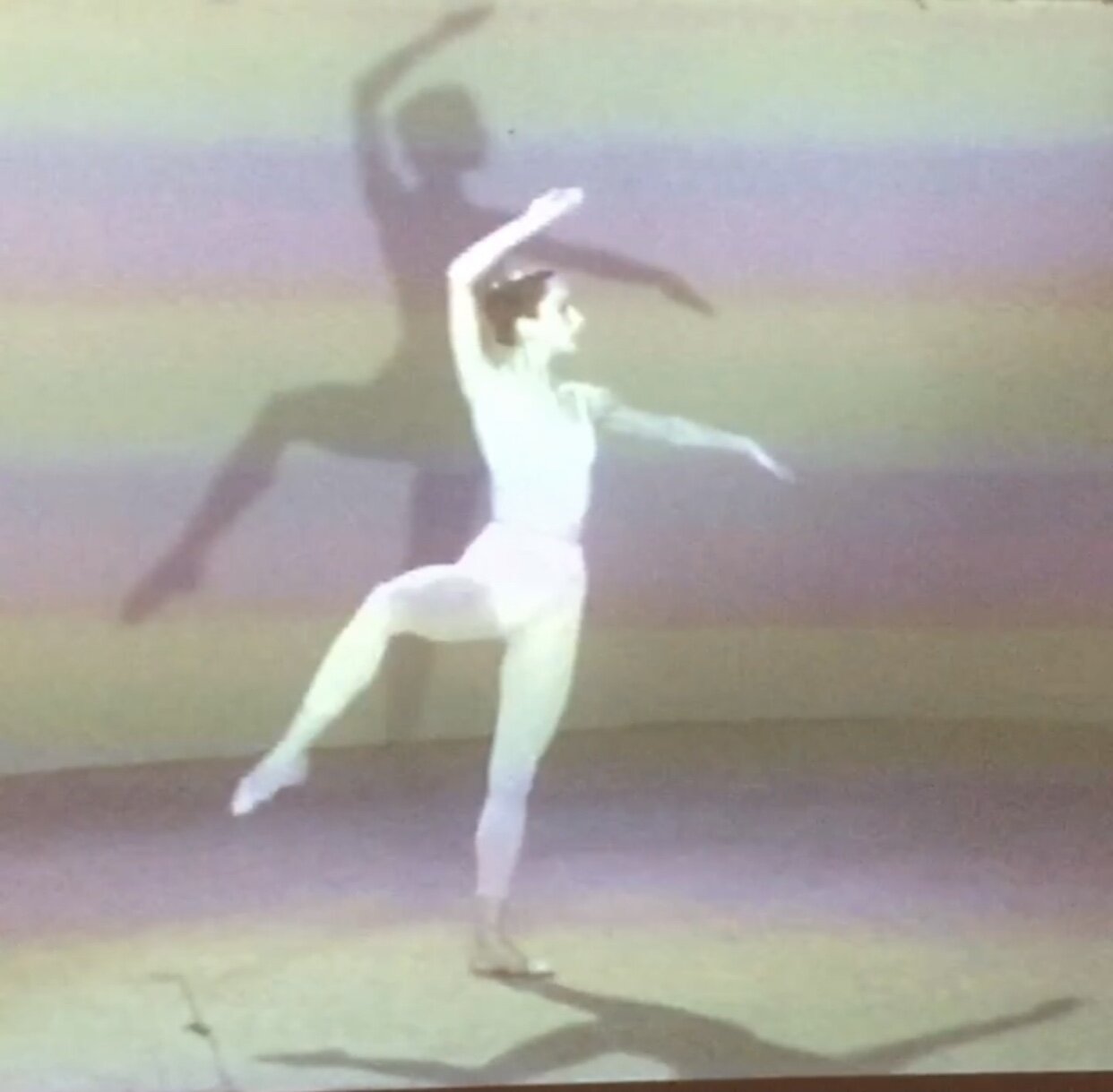

For centuries, women had been portrayed in the arts as allegories, metaphors, symbols: tokens of something beyond themselves. (That’s what Balanchine meant when he said, in 1958, “Put sixteen women onstage as it’s everybody, it’s the world. But put sixteen men on and it’s always nobody.”) But in “Suite for Five in Space and Time” (1956) and its abbreviated “Suite for Two”, Cunningham gave Brown a solo of complete purity and objectivity, in which the dancer is simply this dancer doing these movements in this space and this time. (These photos are taken from a 1958 film of Brown dancing “Suite for Two”.)

No solos were ever more spatially multi-dimensional than Cunningham’s: you see the dancer discovering space, often like unknown terrain or like a blank canvas. And - the factor for which Cunningham remains most renowned - the solos are independent of their music. Brown’s purity amid the formal procedures of this solo makes the movement about itself. Although she has admitted she believes most Cunningham works have hidden stories or subject matter, she has insisted that “Suite” is truly the movement being about itself, about the dancer being herself.

Yet Cunningham was invariably drawn to ambiguity. Despite the objectivity of the movement here, it’s possible to see Brown here as a creative artist, in particular one of the New York action painters of the day, carving out space like a sculptor before advancing across the stage. The whole “action” use of space is related to the Abstract Expressionist painters’ and sculptors way of dramatising space and movement. (Since the 1940s, Cunningham’s performances had drawn audiences dominated by experimental visual artists, among whom Willem de Kooning is now the most celebrated.) It’s impressive that Cunningham, early in his work with Brown, gave her role that kind of authority.

We watch her not just as a mover, but as a thinker. The solo is both a work of art and a soliloquy, whose thought keeps changing with the in-the-moment immediacy of one of Shakespeare’s monologues. Cunningham dancers to this day speak of the exceptional freedom that his choreography gives them: by no means the freedom to improvise, but the freedom to make the movement their own in time and space. At one point, balanced in arabesque (foot flexed), she gently sways from side to side: the impression is of a Calder mobile.

Brown danced this solo up to the end of her Cunningham career. It has been danced beautifully this century by many other women: my mind immediately flies to the seraphic Andrea Weber in the final years of the Cunningham company and the doe-like Vanessa Knouse in a number of performances since 2016. But the film of Brown never dates. She studied ballet with Margaret Craske and Antony Tudor: the rigour she learnt from them - and that was part of her New England nature - remains thrilling. The dancer-choreographer David Gordon once called her “prima modernina”, but it was not a putdown: he has spoken in recent years of the thrill of watching her, and of comparing her to Viola Farber.

Brown wrote an important, scrupulous memoir, “Chance and Circumstance: Twenty years with Cage and Cunningham”, published In 2007. It’s closely based on the letters and other writings she made at the time - and often suffers accordingly, reliving the grievances of years past, and lacking the distance she was often able to achieve in other writings even during her Cunningham years, as in her superb essay to the Cunningham issue of “Dance Perspectives”. Nonetheless Brown always shows that, though she has earned the right to criticise Cunningham, she will suffer almost nobody else to do so; few dancers have charted their roles and dance experience with the heroic detail and reflectiveness she achieves here. She has remained close friends with another founder member of the company, Marianne Preger, whose 2019 memoir, “Dancing with Merce Cunningham” should be read as a counterbalance to Brown’s: the two women, both devoted to Cage as well as Cunningham, had friendly discussions in the 1950s that continue here.

Brown ends “Chance and Circumstance” on the note of passive aggression that has often occurred during the book. Recording how Cunningham, crippled with painful arthritis in 1998, told her “I love you,” she adds “And, at last, I believed it was true.” Yet Cunningham had made great dances for Brown between 1953 and 1972, in such enduring classics as “Suite for Five”, “Rune”, “Summerspace”, “Crises”, “Night Wandering”, “Winterbranch”, “How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run”, “Scramble”, “RainForest”, “Walkaround Time”, Second Hand”. In what better way can a choreographer keep telling a dancer of his love?

Sunday 21 March