The heroic simplicity of Isadora Duncan: Women’s History Month in Dance, 2021

Women’s History Month in Dance 117; 118; 119; 120; 121. The late dance historian Nesta Macdonald never completed the biography of Isadora Duncan she commenced in the 1970s, but she researched much of it in astounding breadth and depth. She often made the point that California in the 1890s had many girls and young women who danced rapturously, barefoot, without corsets; that this aspect of Isadora was unoriginal. The corseting and long petticoats of the late Victorian era were injurious and unhygienic, impeding breathing and collecting dirt; young women rebelled, especially in the United States, whose more outspoken and inquiring women made immense and sometimes disturbing impressions on their visits to Europe. According to Macdonald, one of the discoveries that transformed Isadora Duncan (1877-1927) came when she first performed in London in 1900. Her taste in music up to that point was not advanced; she was fond of light music by Ethelbert Nevin. The critic of “The Times” made the suggestion - when Isadora asked advice - of improving her choice of music: he suggested Chopin. (Isadora later spoke of having danced to Chopin before reaching Europe, but, if she did, she did not realise until Europe how great music could transform her art.)

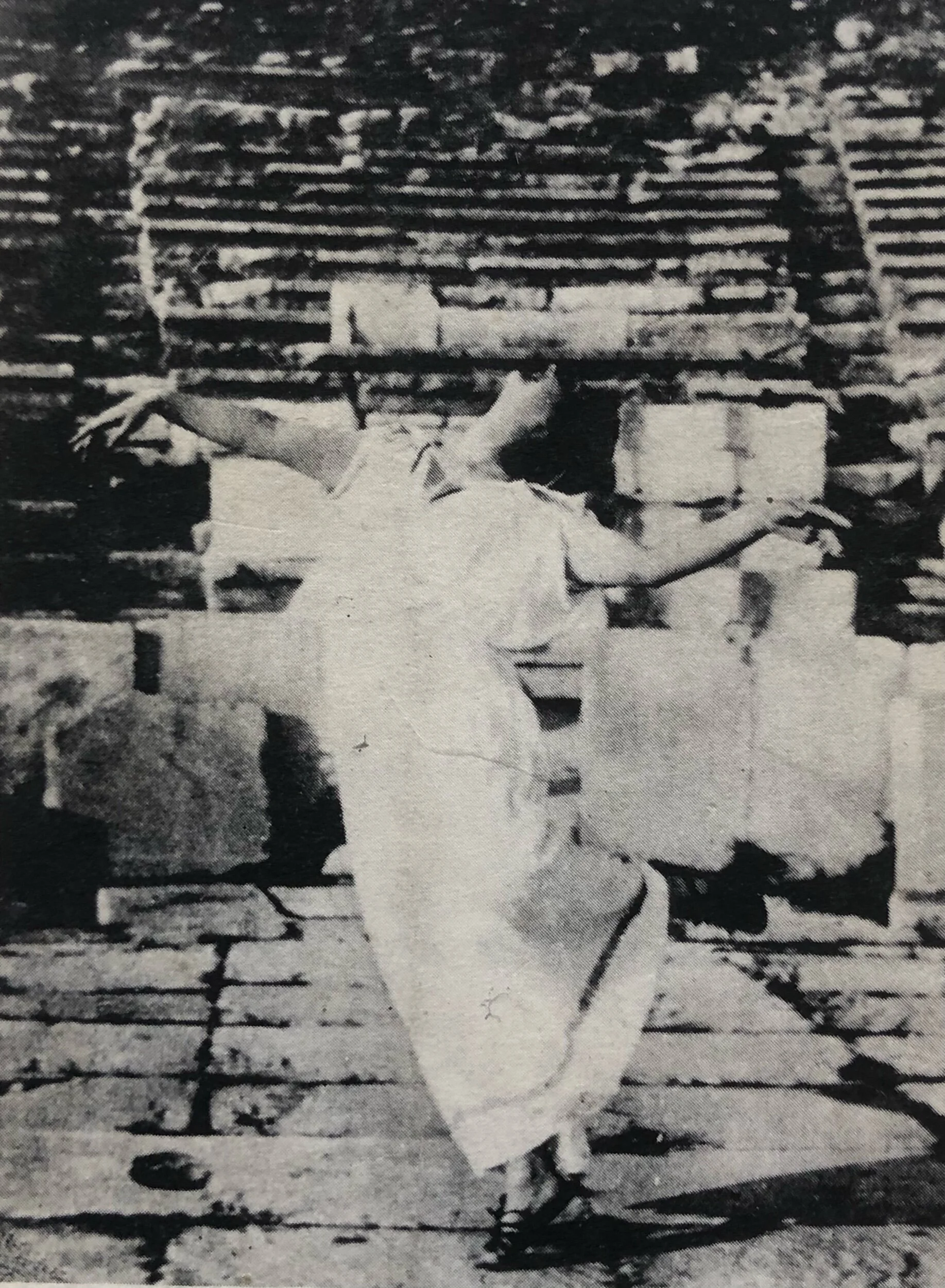

Isadora, in her unreliable but compelling memoirs “My Life”, did not write of that - but she did write of the epiphany that London’s British Museum brought in its wealth of Greek sculpture and its reading room. She also wrote of discovering the solar plexus as the crater of all human movement. This sense of physical centering, of expansive and rapturous neo-Grecian movement as suggested by the nymphs and maenads of sculptures, combined with a profound response to the classical music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Gluck, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Wagner, Brahms, Tchaikovsky) helped the young Isadora to transform her idiom into one that came as a revelation to Europe and, when she returned there, America. At a time when ballet had become fixated on virtuosity and bravura, she brought beauty and power to the simplest movement: standing, walking, running, skipping, lying, twirling. She needed no painted scenery; she often performed before sheer curtains or in grand architectural spaces.

She became an idea, a vision of inspired human potential, variously interpreted and influential across many countries. For some, it was her simplicity and power of gesture that mattered most; for others, it was her use of great concert-hall music at a time when most ballet music was relatively trite. Then there was her demonstration of Grecian style in movement. Perhaps largest of all was her heroic demonstration of how a lone woman might invade space with no male partner.

Isadora’s offstage life was tied up with many men. Onstage, however, she showed that a woman had powerful meaning without any man. Nakedness and nudity took on new vitality in her unadorned movement; she was prepared to expose one or both breasts onstage, but already her revelation of the bare foot, the unclad calf and thigh, the uncorseted torso, all made immense, thrilling, shocking, vital impacts.

With age, her dancing acquired new notes of Expressionism. She danced the anguish she felt on the accidental death of her two young children in 1913; she danced the heroic sympathy she felt with the Bolsheviks of . Russia. But the early elements of her greatness remained. Frederick Ashton, who saw her in 1921, never forgot how she could stand still and then make a tiny movement that registered profoundly. The chief dissenter was George Balanchine: he, who also saw her in 1921, described her as “a drunken, fat woman who for hours was rolling around like a pig.” Balanchine made a number of nasty and/or ungenerous remarks about famous dancers, including those he had not seen (Marie Taglioni, Vaslav Nijinsky); he hated hype. Still, his resistance to Isadora and malice about her were foolish: the wealth of running that infuses his “Serenade” is indebted to Isadora, the barefoot opening movement of his “Tschaikovsky Suite no 3” would have been inconceivable without her, and his whole lifelong project of dancing to great concert-hall music was a continuation of her legacy.

The choreographer Mikhail Fokine denied copying her, but always praised the epiphany of her use of simplicity; Serge Diaghilev simply said that all Fokine’s work was Duncanist. Ruth St Denis was just one of many modern dancers who praised Duncan in the highest terms; Mary Wigman and other German modern dance figures were all borne by the vast wave of enthusiasm that Isadora created across Germany.

Tuesday 30 March

117: Isadora Duncan dancing in the Theatre of Dionysus, Athens. Photograph by Raymond Duncan.

118: Isadora Duncan, photographed by Arnold Genthe

119: Isadora Duncan

120: Isadora Duncan, by Abraham Walkowitz, c.1920

121: Isadora Duncan, photographed by Arnold Genthe