A faded postcard from Antoinette Sibley

Here’s a faded postcard that prompts many enchanted memories. The ballerina Antoinette Sibley had two careers, the first from 1957 to 1976, ending in a major flareup of a recurrent knee injury while she was filming “The Turning Point”. She spent two years and a half in 1976-1979, trying to regain form in class; some observers felt she really had succeeded, but certainly she decided in spring 1979 that her knee would no longer permit the thirtytwo fouetté turns of “Swan Lake” (she had sometimes embellished them with double pirouettes) or the double sauts de basque that had been part of George Balanchine’s “Ballet Imperial” in the 1950 text that the Royal Ballet had preserved, a role that had been one of Sibley’s most valued for at least fourteen years of her career. Therefore, two or three months after reaching her fortieth birthday in 1979, she announced her retirement from the stage.

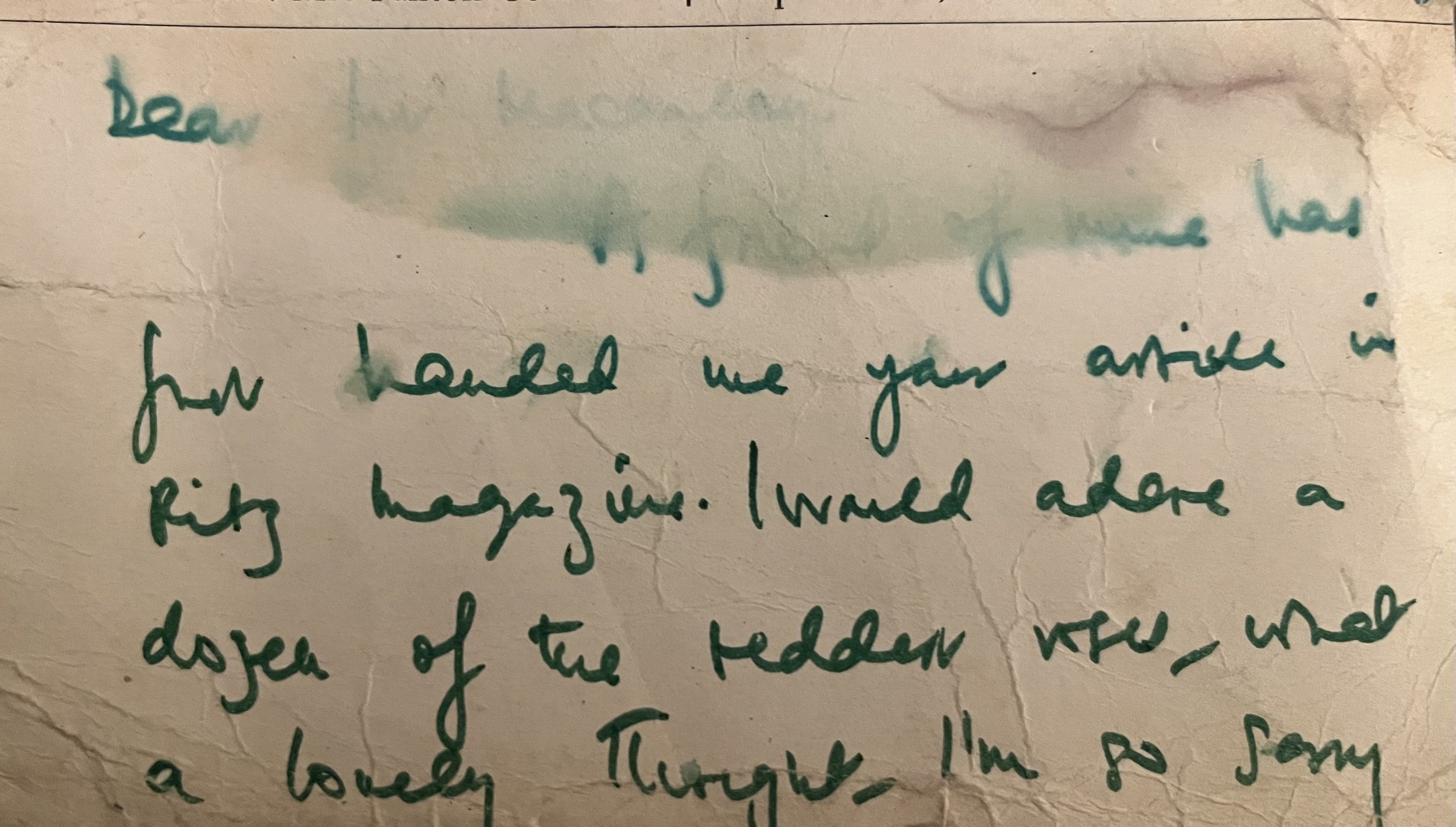

I had only seen Sibley dance once, in a 1976 performance of Frederick Ashton’s “Thaïs” Meditation pas de deux. I had pored over photographs of her, however, and had booked for her 1976-1977 performances in such roles as Titania and Juliet from which she had then withdrawn. Soon after the announcement of her retirement, I happened to be in Belgrave Square, buying flowers for a friend who lived nearby, when I spotted Sibley. I promptly also bought a dozen red roses and chased off to give those to her - but too late: she had vanished. (She lived - still lives - nearby.) But I had a dance column in the monthly “Ritz” Newspaper, in which I promptly narrated the story of these red roses, and, in telegram-like format in upper-case letters, asking Sibley to contact me c/o “Ritz”; so that I might deliver “a dozen of the reddest roses” to her.

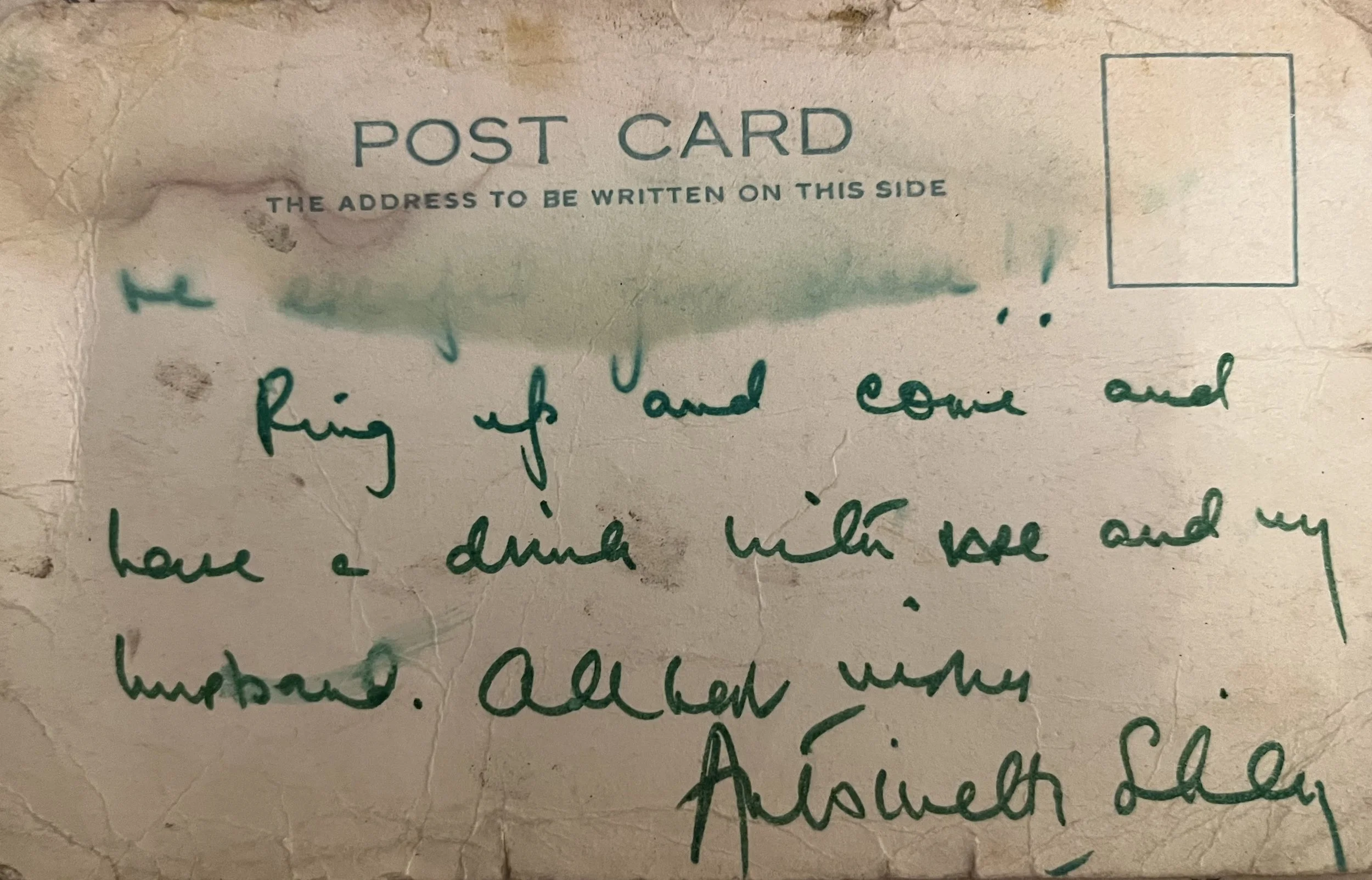

Six whole months after publication, Sibley indeed contacted me (as you see here), saying “I would adore a dozen of the reddest roses, what a lovely thought,” and inviting me to visit her one evening for a drink. (This postcard was topped by her postal address, which I omit here to preserve her privacy.) Sure enough, I rang her as she requested; I then spent, in December 1979, a long and rich evening in deep conversation with her about her career.

I had just returned from the Bournonville Festival in Copenhagen, when the Royal Danish Ballet danced under the direction of Henning Kronstam. She glowingly recalled dancing for Erik Bruhn in the Royal Ballet’s “Napoli” pas de six, and dancing with Henning Kronstam in other engagements. I told her of having seen Niels Bjørn Larsen’s silent 1955-1966 film of Frederick Ashton’s “Romeo and Juliet”, which she had never seen.

But we also spoke in detail of “The Sleeping Beauty”, a ballet in which she had danced many junior roles as well as (from very early on) Princess Aurora. That role was still vivid in her mind; she talked me through almost all of its dance numbers. For example, she told me how, in Aurora’s Act One violin variation, whereas Fonteyn had just glided through its linking steps, she, Sibley “just had to” enounce those glissades. She also recalled that, where Fonteyn had found Act Three singularly taxing, she, Sibley, found it far more congenial than Act One. In particular, she recalled how Fonteyn, perhaps around 1973, once had congratulated her after an especially fine account of Act One, but had then added “But now you’ve got Acts Two and Three to go!” Sibley had been able to reply “Oh no - those acts never alarm me!”

She took me through Aurora’s great Act Three variation almost step by step. Fascinatingly, she told me that, in 1963, she, in her twenties, had been asked to teach the role to the much-loved Violette Verdy, who was to dance it as a guest with the Royal Ballet. Sibley said “There are two kinds of musicality. When Margot (Fonteyn) or Monica (Mason) or Lynn (Seymour) or Anthony (Dowell) or I danced, we were the music. But there’s another kind of musicality that can be more wonderful, where the dancer plays with the music. Merle (Park) has that; and Violette has it to an even greater degree. When it came to the opening phrase of that variation, I taught Violette what we had always done at the Royal. But she at once said ‘No, I have to do it a beat ahead!’” Sibley said “And what was so marvellous was that I knew immediately I had to do it that way - I poached it from her! - and, though Violette only danced the role that season, I danced that way for the rest of my career!”

(Over thirty years later, Lynn Seymour told me that she too had stolen Verdy’s way of phrasing the start of that variation. Not long afterwards, I met Verdy, and took the opportunity of telling her that Sibley and Seymour had always treasured the memory of her phrasing of that variation, but Verdy, always generous and merry, laughed enthusiastically: “Oh, those girls didn’t need to learn anything about musicality from me! And that Merle Park!”)

Sibley’s memories of that variation did not stop there. She talked me through the sublime diagonal of sixteen petits développés, showing me (sitting down) how eyes, wrists, hands, and feet should be co-ordinated in an ever-increasing cylinder of space. (Today, no Aurora at the Royal Ballet, and few anywhere else, shows this sequence of sixteen steps as a single accumulating crescendo, even though evidence shows Petipa wanted it that way.)

If I recall correctly - though here I question my own memory - she described how beautifully Violetta Elvin had delivered the petits développés. (I question my memory here, because Elvin retired from the Royal Ballet in 1956, while Sibley was still a student.)

But where I trust my memory completely is of Sibley’s account of this variation’s final manège around the stage. “I must admit that was where I came into my own: I tore the place up!” I knew at once what she meant, because of a single haunting photograph I knew: the manège begins with turning relevés grands développés à la seconde, usually delivered with Aurora looking either out to the audience or downward in the direction of her rear, left hand; but the photograph showed how Sibley, as if in triumphant jubilation, looked up into the air to her raised right hand.

I was twenty-four; I had never spent more than a minute with any ballerina before. Here was Sibley, looking back on her past career, talking expansively to me, still a newcomer to criticism, for more than two hours.

Other surprises followed in the 1980s. Perhaps Sibley already knew when I saw her that she was pregnant with her second child; she gave birth to a beloved son the following summer. A few months after that (November 1980), after eighteen months of not taking class at all and at age fortyone, she was coaxed back to the stage by Anthony Dowell and Frederick Ashton, dancing the premiere of Ashton’s “Soupirs” pas de deux at a charity gala that Dowell organised. To her amazement, when she prepared by giving herself a barre (“Your weight goes back when you’re pregnant”), she found that her problem knee was no longer a problem. And when her calves began to cramp a little, she tried going on point, whereupon she found that pointwork, too, returned easily. Creating the pas de deux for Ashton and with Dowell, she was able to dance both on point and with all her former upper-body plasticity. (I’m inclined to think that, of all the Royal Ballet major ballerinas, Sibley and Lynn Seymour had the most lavish épaulement of all.) She later said that she suspected Dowell and Ashton had been conspiring to lure her back to the stage; that they, like others, had always felt she had never needed to announce her retirement.

Gradually from then on, she rebuilt strength and stamina, between 1982 and 1988 returning to such roles as Nikiya in the Shades scene of “La Bayadère”, Raymonda in “Raymonda Act Three”, the wedding pas de deux of “The Sleeping Beauty”, as well as such Ashton roles she had created as Titania (“The Dream”), “Jazz Calendar”’s Friday’s Child, Dorabella (“Enigma Variations”), the “Thaïs” Meditation, and the title role of MacMillan’s “Manon”; also such treasured Ashton roles as the ballerina of “Scènes de ballet”, the heroine of Daphnis and Chloë (final scene only), and the three-act “Cinderella”, and the dramatic role of Ophelia in Robert Helpmann’s “Hamlet”. She even created another new role for Ashton (“Varii Capricci”) and new roles for choreographers Michael Corder and Derek Deane, and danced for the first time one of the lead roles in August Bournonville’s “Konservatoriet” (the classroom scene), the Débutante in Ashton’s “Façade”, the Fonteyn role in his “Birthday Offering”, and Natalia Petrovna in his “A Month in the Country”. In many of these, her partner was Anthony Dowell as before, but now she experimented more than before with new partners, dancing rapturously with Michael Batchelor, Baryshnikov (who had always treasured the memory of Sibley’s and Dowell’s encouraging generosity to him while he was still with the Kirov Ballet in 1970), Fernando Bujones, Wayne Eagling, Stephen Jefferies, Nureyev, Peter Schaufuss, and David Wall. She gave her final performances (with Dowell, in “A Month in the Country”) in December 1988, soon after Ashton’s death; it was as if her second career had all been connected to that choreographer.

Both in those 1980-1988 years and later, I interviewed Sibley again. She was invariably spontaneous, evocative, and generous; but her memory, though full of rich detail, became patchy. Anyone who has watched her and Dowell coach younger dancers in their Ashton creations will have seen how Sibley often says to Dowell “What comes next, darling?” and then, when prompted by him, demonstrates, fabulously, the movement she had forgotten a moment before. I especially remember asking her in 1984 about what Nureyev had said to her about “The Sleeping Beauty” in the Royal Ballet‘s canteen: she had said in an interview that once she had told him of her loss for inspiration in this familiar classical role, whereupon he had spoken to her about the ballet so thrillingly that “I will never forget” his words, which had always carried her through subsequent performances. Alas! as happens to all of us when we say “I’ll never forget”, she had now forgotten his words. Some of what she had told me in 1979 had also evaporated from her mind.

Still, there are steps I suspect Sibley may never forget as long as she lives. I last interviewed her in autumn 2014, in the same beautiful drawing room of her Belgravia home as I had visited in December 1979. She was now seventy-five, but she rose to show me - exquisitely - the ronds de jambe à terre Ashton had loved her dancing in “Napoli” and had put into her Dorabella “Enigma” variation: her upper body and lower body effortlessly combined to show the movement to perfection. Yet more poetically, though just sitting down, she showed me the sideways-tilting upper-body movement of the “Oriental” variation in “Scènes de ballet”. That very evening, I watched a much younger ballerina dance that very role at Covent Garden, but with only a minor fraction of the full-bodied perfume that Sibley had shown me in her drawing room.

Perhaps the three ballerinas who did most to inspire me and show me what ballerinadom could be were Margot Fonteyn, Lynn Seymour, and Suzanne Farrell, women all superbly unlike myself and extending my idea of dance’s potential. But in the years 1980-1988, when I so often watched Sibley (I missed almost none of her Covent Garden performances), I often felt - though this seems crazy to me now - as if she embodied something of my own self; that her way of dancing epitomised my own inner self. She was also then - and probably remains - the ballerina about whom I felt I wrote best: that I was now, thanks in part to her, a good enough writer to capture enough of her essence in print.

All these memories now arise from the few words in her handwriting on this 1979 postcard. I am forever grateful.

Monday 15 January

@Alastair Macaulay 2024