MerceDay 9: lost dances of the Cunningham-Cage-Rauschenberg dance theatre enterprise

MerceDay Continued, 9. One of the astonishing aspects of Merce Cunningham’s choreography is how much advance work went into creations many of which had a very limited life in performance. Sometimes good or marvellous works were rejected by unsympathetic but influential critics. Other first-rate creations somehow didn’t gel with their music and/or designs in ways that proved theatrically satisfying. Yet others lingered only while their original casts did: Cunningham didn’t keep them in repertory after those first interpreters had departed: like many other great choreographers, he was more concerned with his latest work than in revivals. Individual dances survive from many otherwise lost Cunningham works, but we can only guess how the originals were as wholes.

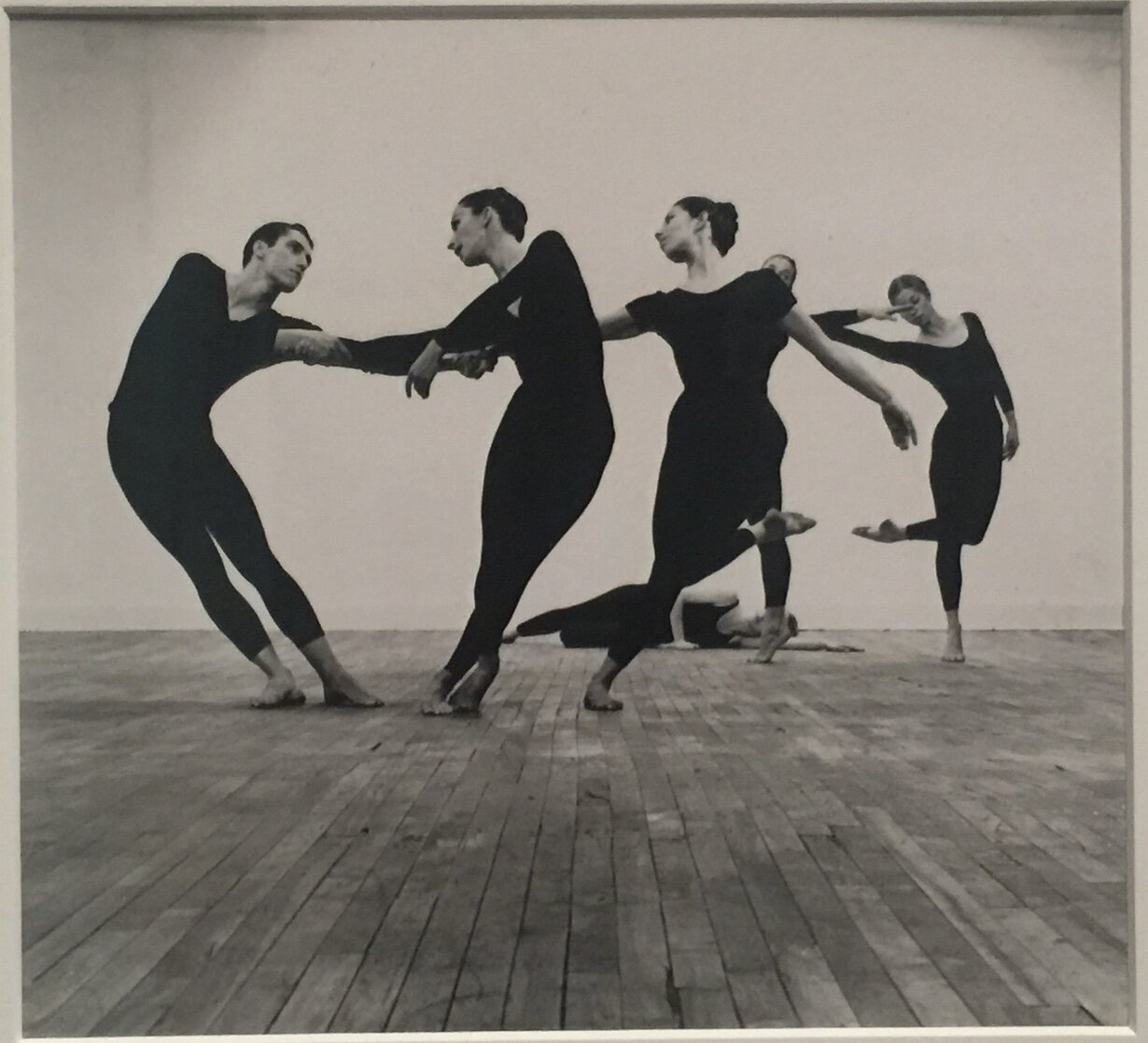

The surviving remnant of “Aeon” (1961) today is a female duet, revived in a few Events, using billowing wing-like fabric. But the complete “Aeon” had roles for six women and three men. Apart from Cunningham himself and Remy Charlip (a founder member of the Cunningham company who was soon to depart), the third male role was the first made for the remarkable Steve Paxton, whose authority and force is evident on the left of this photograph (taken by Robert Rauschenberg): he and Carolyn Brown are pulling away from each other. The other dancers are identified as, left to right, Judith Dunn, Marilyn Wood, Viola Farber, and (lying at the back) Shareen Blair. Brown has recalled the Blair-Brown-Dunn-Farber-Wood nucleus as a golden era for the young company, though Dunn and Wood both departed in 1963 and Blair left the company (to marry) during the 1964 world tour.

“Aeon” was a creation by Cunningham, John Cage, and Robert Rauschenberg, the three who had established the perameters of Cunningham dance theatre since 1954, three theatre artists of equal weight creating independently e elements that came together onstage. I would love to have seen this, “Aeon”, simply because Cunningham described it as “epic in character”. A later dancer, William Davis, likewise said “It was vast and expansive.... It was like the history of the race somehow, <with> events or all kinds: little ones, big ones, cataclysmic ones, things that looked like war and pestilence, some lyric things.... It had scope, and it was really wonderful and difficult to do.”

Cunningham had been choreographing since 1942, and had had a formal company since 1953. Those who believed in his work knew it to be great. Yet he was still an outsider, unknown to large parts of the dance world, and only since 1958, thanks to the annual American Dance Festivals of 1958, 1959, 1960, and 1961, achieving the status of an intensely controversial heretic. Not until the world tour of 1964 was his work reviewed by the “New York Times”, and never by John Martin, whose word had been law for earlier generations of modern-dance choreographers. Nonetheless those 1958-1961 American Dance Festivals created more believers and some new momentum for the Cunningham enterprise. “Aeon” had its premiere in Montreal, before appearing at the 1961 American Dance Festival, which in that era was held at Connecticut College.

Rauschenberg left the Cunningham enterprise in 1964, at the end of the company’s world tour. He had not been its only designer in the 1954-1964 years, but the list of Cunningham works with Rauschenberg designs includes “Minutiae” (1954), “Suite for Five in Space and Time” and “Nocturnes” (1956), “Labyrinthian Dances” and “Changeling” (1957), “Antic Meet” and “Summerspace” (1958), “From the Poems of White Stone”, “Gambit for Dancers and Orchestra”, and “Rune” (1959), “Crises”, “Hands Birds”, and “Waka” (1960), “Aeon” (1961), “The Construction of Boston” (1962), “Field Dances” and “Story” (1963), “Paired” and “Winterbranch” (1964). Several of these have a legendary status even among those who have never experienced them in the theatre: they did more than any other works of dance theatre to resume and extend the Diaghilev principle of making dances that employed major painters as their visual designers. Not all of them had scores by Cage, but several; Cage said on a number of occasions that Rauschenberg and he were so like-minded it was uncanny, whereas he felt that Cunningham and Jasper Johns were artists thoroughly unlike him in ways that he admired and enjoyed.

It took a long time for Rauschenberg to return to the Cunningham fold, but, when he did so in 1977 (fir “Travelogue”), it was to a Cage score. After Cage’s death, Cunningham commissioned two more designs from Rauschenberg: in 2000 for “Interscape” (perhaps the most beautifully heroic of all Rauschenberg’s theatre designs) and in 2007 for “XOVER”: both these were to scores by Cage.

Friday 16 April