Nearest to the Workings of Shakespeare’s Mind - “Love’s Labour’s Lost”, 1979

First published in Areté in 2013. Dedicated to Craig Raine, that excellent magazine’s editor.

Forty-three years on, I can still hear their voices. Richard Griffiths, with his strangely bottled-up vocal resonance and un-urbane, donnish temperament, was the King of Navarre; Michael Pennington, with his more suave and refined vocalism and searching intelligence, was the famous wit Berowne. And the lines that haunt me most are these:

King: But what of this? Are we not all in love?

Berowne: O! nothing so sure; and thereby all forsworn.

This exchange occurs in Act IV Scene 3 of Love’s Labour’s Lost, a play I’ve now seen and reviewed a number of times. To me, however, they - and much else of the play – remain forever part of the most revelatory theatre production of my life. It was 1979; I was not then a theatre critic. (I had become a dance critic the year before, in 1978; theatre criticism began in 1990.) John Barton’s staging had been new the year before in Stratford-upon-Avon; now it ran in Royal Shakespeare Company repertory throughout the summer at the Aldwych Theatre in London, the company’s London home. I had both read and seen the play; until this production, I thought I knew it.

Love’s Labour’s is often given as a romping farce about gilded youth being suddenly tripped up at the end by tidings of death. Its central four men - the young King of Navarre and three of his courtiers – are bookish but immature students who play pranks but find themselves discomfited by the Princess of France and her three ladies, whom they court. Only late in the long finalscene does the messenger of death arrive, bringing the news of the demise of the Princess’s royal father. Comedy is at once suspended. Most modern productions update the action: afavourite device of directors is to locate it in the Grantchester years of the Lost Generation, the idyll before the First World War.

Barton’s production, by contrast, made the announcement that the King of France is dead only the most drastic of the play’s many extraordinary turning-points. The two lines I’ve quoted became its most subtly profound change of key. They came after a scene that this production made one of the most hilarious in all Shakespeare. This playwright is a master of eavesdropping as drama: there are celebrated comic examples of it in Twelfth Night and Much Ado About Nothing, tragic examples in Hamlet and Othello. This Love’s Labour’s scene of multiple spies is – so this production established - his most virtuoso example. The four men, though they have sworn to stay out of love, have fallen into it anyway. Berowne, who has written a love-poem for Rosaline, hides and listens in on the King, who reads aloud the love-poem he has written for the Princess. Next, however, the King secretes himself elsewhere, so that he can overhear Longaville, who, arriving, promptly reads aloud his love-poem for Maria. Sure enough, when Dumaine arrives, Longaville hides.

Multiple spies; and multiple hypocrites. When Dumaine reads his love-poem for Katherine (Kate), Longaville, pretending to be still chaste in heart, emerges to denounce him for breaking his vows – whereupon the King, revealing himself and claiming himself as true to his oath, denounces them both. He’s wondering aloud just how Berowne would rebuke them when Berowne, appearing, puts him to shame by revealing what he has heard. And Berowne - though he earlier in the same scene has privately hoped that his three friends are in the same lovelorn situation as himself - cannot now resist claiming to be the sole immaculate one of their number:

“I, that am honest; I, that hold it sin

To break the vow I am engaged in.”

On cue, in comes a messenger to deliver, by accident, his own love-letter to Rosaline. He not only rushes to admit his own guilt, he declares ardently that they should all embrace, driven to love by their young blood. His friends, though, are merciless. For every peak in which he praises Rosaline, they find a trough. They’re overgrown schoolboys; their ragging has the high spirits of youth. Though I never witnessed a Shakespeare production in which verse was better spoken, Barton also allowed this to become a scene of knockabout brawling; and it ended with all of them flat on their backs, exhausted by their own laughter. The scene was staged so that the audience laughed with them, long and hard.

Then, as they lay there, weak with laughter, Griffiths, looking up, asked in reedy oboe-like tones that suddenly ended the merriment:

“But what of this? Are we not all in love?”

He spoke it almost like a scholarly objection to a philosophical proposal. And Pennington at once replied with suave firmness:

“O! nothing so sure; and thereby all foresworn.”

The words were a cloud suddenly passing over the sun. The mood changed forever. Berowne has been telling them that they will break their vows since line 149 of the play’s opening scene (“Necessity will make us all forsworn”). Till now, though, they’ve been in denial. Only now do they face up to their dilemma.

As a Classics student a few years earlier, I had learnt from Aristotle's Poetics the theory that tragedy depends upon peripateia, reversal, and anagnorisis, recognition. But Oedipus Tyrannus and other Greek tragedies tend to feature just one overwhelming reversal, and one drastic recognition. From this Love's Labour's, I learnt that comedy can have these things too - and, more remarkably, that it can abound in them. Just as Jane Austen’s Emma does not need a single lesson but successive ones to learn how she has been misapplying her cleverness, so it is with these four young men in Shakespeare’s Navarre, from early in the play.

Opposite these men were worthy foils: Carmen Du Sautoy as the Princess of France and Jane Lapotaire as her chief companion Rosaline. Du Sautoy, bespectacled like Griffiths and with a touch of the bluestocking, matched his bookishness. (It seemed that neither of these royal personages was quite ready for the adult world of the court.) Lapotaire - whose voice was, unforgettably, at once nasal and mellifluous - combined acidity, merriment, and piercing honesty. When the four Navarrese lords first approached the four French ladies (Act II Scene 1), each conversation was like a joust, often conducted in classic stichomythia, the rapid-fire exchange of single sentences developed in Greek drama. When Pennington/Berowne came up to Lapotaire/Rosaline, they made the iambs bounce:

Berowne: “Did I not dance with you in Brabant once?” (In Wagner’s Lohengrin, the stress in “Brabant” is on the second syllable, but in Shakespeare it’s on the first.) Pennington made it a polite inquiry, stressing “dance” and “Brabant”.

Rosaline (knowing that his question expected the answer “Yes” but instead, by echoing him, confounding him): "Did I not dance with you in Brabant once?” Lapotaire, though speaking quickly, stressed “you” with some archness.

Berowne (thinking that he has scored a point in this courtship): “I know you did.”

Rosaline: "How needless was it then to ask the question." Lapotaire, turning smartly on her heel, turned that last reproof into her Parthian shot that left Berowne/Pennington wonderfully worsted. (In the play, their exchange has further lines; Barton cut them.)

Rosaline’s wit is part of what infatuates Berowne. It was easy to feel that Pennington’s emotion was the one Jane Austen attributes to Darcy after an early exchange with Elizabeth Bennet: “There was a tolerable powerful feeling towards her, which soon procured her pardon.”

For many as well as myself, this remains the classic account of the play. (A friend who is an actor-director recently wrote to me that it remains always in his mind as the epitome of how to keep a play entirely new.) The cast also featured Michael Hordern (Don Adriano), David Suchet (Sir Nathaniel), Paul Brook (Holofernes), Alan Rickman (Boyet), Ian Charleson (Longaville), Allan Hendricks (Costard), and Ruby Wax (Jacquenetta): in most cases, I hear their voices, too. Ralph Koltai's décor had unobtrusive trees starting to shed leaves. His costumes - approximating the late Elizabethan period without detailed specifics - were simple and sketchy; Berowne was dressed like a monkish penitent. Nick Chelton’s lighting filled the air with warmth. The emphasis was all on the language. Love’s Labour’s has the most intensely pedantic conversations in Shakespeare; this production made them lucid and delicious, so that I still laugh to hear in my head the fusspot way in which Holofernes/Brook said such lines as “You find not the apostrophus, and so miss the accent; let me supervise the canzonet.” Twenty-two years later, interviewing Barton, I complimented him on this definitive production; he said simply that he had had very good actors. He had; I had loved them then. But the great discovery was neither the skill of their acting nor even the lesson they gave in the brio, elasticity, and architectural command with which Shakespeare's verse can be spoken; it was the play itself, revealing here an internal complexity and moral depth I have never found in it before, while also becoming its playwright’s funniest.

Even when Berowne darkens the mood in Act IV scene 3 with “O! nothing so sure; and thereby all forsworn,” he and the other young men have not learnt their full lesson. Remaining devoted to cleverness rather than to emotional honesty, they call upon Berowne, the smartest wit and most splendid orator among them, to make them feel that somehow the pursuit of love resolves their oath-breaking. He obliges them in a dazzling seventy-six-line speech (“It is religion to be thus forsworn”).Pennington’s shaped the speech, thrillingly, as a perfect crescendo.

Yet this triumph of wit proved yet another of the play’s examples of hubris. When Berowne and his chums next press their suit on the ladies, in the play’s long and amazing final scene, they do so absurdly, with disguises. The ladies, with no reason to take their courtship seriously, fool them by wearing masks and changing favours. Each gallant declares love to a different woman than the one of his intention. More reversals; more recognitions. And even when Berowne tries to cut through the games to press his suit, his language remains too polished to sound sincere: “My love to thee is sound, sans crack or flaw.”

I can hear the tender mockery in Lapotaire’s voice as she replied: “Sans ‘sans’, I pray you.”

I began to understand then that Love's Labour's Lost is one of those several works in which a supremely witty artist tackles the subject of how wit must be defeated; wit is fruitless until it is tempered by wisdom. This theme, to artists who are both wits and moralists, is natural terrain: it recurs in Molière, Congreve, Austen, Wilde, and Stoppard. Shakespeare’s variations on it are innumerable; his plays continually show brain being worsted by heart, the difference between cleverness and good sense, the futility of learning without feeling.

Alongside the four lords who court the French ladies is a secondary cluster of characters, two of whom – Armado and Holofernes – compete in preposterously learned parlance. They too are seen to come a cropper, in their feckless play of the Nine Worthies; but the play’s greatest lesson is something much larger than their fiasco. The play-within-the-play is, like eavesdropping, one of Shakespeare’s most telling devices; Barton’s Love’s Labour’s play taught me to love this scene even more than the celebrated play scenes in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Hamlet. The four lords are heartless in the fun they have at its expense; what’s wonderful are the remarks spoken out of character by its players.

First, when the nobles have rubbished Sir Nathaniel’s effort as Alexander, Costard (played by Allan Hendricks with life-enhancing warmth) send him packing with a tender rebuke, and then, wonderfully, turns to them and gives this wonderful apology:

“There, an’t shall please you: a foolish mild man; an honest man, look you, and soon dashed! He is a marvelous good neighbor, faith, and a very good bowler; but, for Alisander, - alas! You see how ‘tis, - a little o’erparted”

But even from this the lords learn no charity. They tear cruelly into Holofernes’s act as Judas until there is nothing left of it; and he, though abashed, soberly chides them;

“This is not generous, not gentle, not humble.”

Sometimes I recall this as the production’s most overwhelming moment; Brook uttered it quietly, with good manners, with just enough authority to shame some of his audience. Not, however, the four lords. They are relentlessly laying into Hector/Armado when the irrepressible Costard blurts out that Jacquenetta is two months pregnant with Armado’s child. It’s at this juncture that Marcade enters with the play’s biggest thunderbolt.

It’s a reversal:-

Marcade: “I am sorry, madam; for the news I bring

Is heavy in my tongue. The king your father -”

Astonishingly, the Princess takes it as a recognition. She takes the words out of his mouth:

“Dead, for my life!”

Nobody can ever have spoken this so well as Du Sautoy, at once eager to anticipate the end of his sentence and stunned by her loss.

Though farewells are now in order, the play’s changes of tone keep coming. When the King/Griffiths spoke to the Princess/Du Sautoy of love in high-flown language, she answered simply “I understand you not; my griefs are double,” through tears, as if bewildered. Pennington/Berowne now chimed in, with a beautiful corrective to the King, by saying

“Honest plain words best pierce the ear of grief.”

Berowne’s speech courteously but fully acknowledges how love has made the four male lovers not only forsworn but ridiculous too. The women admit they assumed the courtship had all been in jest. The men assure them otherwise; and the King/Griffiths suddenly insists:

“Now, at the latest minute of the hour,

Grant us your loves.”

I can never forget the sharp, urgent, grief-charged, yet witty asperity with which Du Sautoy answered him:

“A time, methinks, too short

To make a world-without-end bargain in.”

And then the mood changed, once again, as she quietly proceeded to ask him to spend the coming year in a hermitage while she spends the time mourning. If he can do so, she will be his. Katherine, Maria, and Rosaline likewise turn tell Dumaine, Longaville, and Berowne to wait a year. But Lapotaire made Rosaline’s speech to Berowne heartstopping, telling him in unflinching tones to “Visit the speechless sick, and still converse/

With groaning wretches; and your task shall be,

With all the fierce endeavor of your wit

To enforce the pained impotent to smile.”

Pennington/Berowne, shocked and uncomprehending, protested:

“To move wild laughter in the throat of death?

It cannot be; it is impossible;

Mirth cannot move a soul in agony.”

Without skipping a beat, Lapotaire threw the play’s final dart bang on target:

“Why, that’s the way to choke a gibing spirit.”

I can still hear the temper in the iambs as she spoke them.

Each Shakespeare play, I’ve now learnt, is Protean in the way it can reveal itself as something you did not know it to be. Still, Love's Labour's has never revealed itself more completely to me than in Barton's staging. I have never felt closer to the workings of this playwright’s mind.

@Alastair Macaulay 2022

1: Michael Pennington as Berkeley in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 1978-1979 production of Love’s Labour’s Lost.

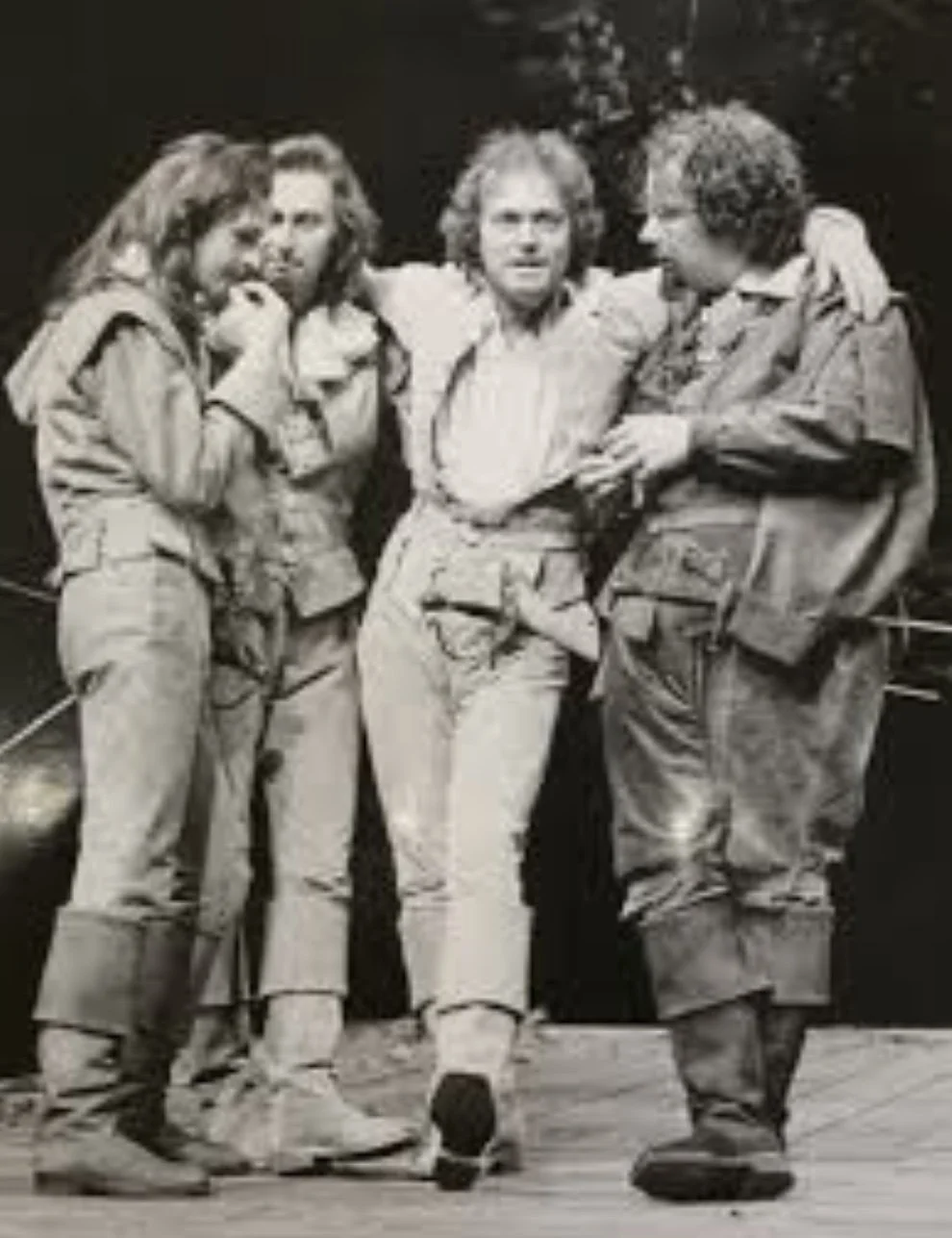

2: From right to left: Richard Griffiths as the King of Navarre; Michael Pennington as Berowne; Paul Whitworth as Dumaine; Ian Charleson as Longaville.

3: Right to left: Jane Lapotaire (Rosaline), Michael Pennington (Berowne), in John Barton’s 1978-1979 production of Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost.