Nijinsky’s notation for “L’Après-midi d’un faune”: a conversation with Ann Hutchinson Guest and Claudia Jeschke

L’Après-midi d’un faune – questionnaire

Ann Hutchinson Guest and Claudia Jeschke with Alastair Macaulay

This conversation was conducted by email in February-April 2017. I was preparing a seminar for and at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts on the subject of Vaslav Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi d’un faune. That seminar took place on May 15 that year. It was filmed for the Library by François Bernadi. Dancers, critics, and scholars who attended and contributed included: Joan Acocella, Mindy Aloff, Juliet Bellow, Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen, Diana Byer, Daniel Callahan, Lynn Garafola, Wayne Heisler, Ann Hutchinson Guest, Michael Novak, Nancy Reynolds, Rachana Vajjhala, Elena Zahlman.

Most of these questions were written and answered in February-March 2017. Later comments arose in April. I add now in 2021 that the several films we watched of “Faune” that one afternoon in 2017 persuaded me and several others that the Hutchinson/Jeschke staging of Nijinsky’s notation is the most revealing, detailed, and expressive - and also the closest to the oldest film (1931) of this work. Debate took place, amid which it was especially fascinating to hear from Steven Melendez, Michael Novak, and Elena Zahlmann about the interpretations possible to the performers of this Nijinsky/Hutchinson/Jeschke text. (Novak and Melendez, playing the faun, each formed different ideas of his motivation with the scarf.)

AM1. How good does Nijinsky seem as a notator? How complete or incomplete in recording movement is the Stepanov movement as he employed it?

AHG1. Nijinsky did not use Stepanov notation in his score of Faune. It was written in his own notation system,derived from Stepanov but much improved.

He was a good notator; he recorded much detail in his Faune score. He maintained his interest in notation from his initial study of the Stepanov system and started recording materials in that system. Later, he made important improvements on the Stepanov system to the point where, even if one knew the Stepanov system, reading Nijinsky's score was not immediately possible. It was the pages of his Cecchetti technique notations that proved to be the Rosetta Stone for Claudia and me. I had studied Cecchetti for years and knew what the classroom exercises and adages were. His notations had the names of the énchaînements written in French above his notations, so I knew what the symbols must represent. He recorded the correct holding of each finger in the balletic hand position, for instance.

AM2. As I think I've heard you say - years ago - one of the crucial points is Nijinsky's length of phrase and how this connects to the music. Is that right? If so, how precise is he in notation with dynamics within the phrase?:- what I would call staccato, marcato, legato dynamics.

AHG2. You refer to my saying how Nijinsky's length of phrase connects to the music. I don't remember saying quite that; his movements relate to the music but not in a parrot fashion, a movement for each note of music. The movement phrases relate logically to the music in telling the story. He certainly indicated sudden, swift actions and long sustained passages. Remember that his notation system uses music notes to indicate timing, so he had a clear understanding of timing. He did not include dynamics as such, the staccato, marcato, legato dynamics you mention.

CJ2. Ann gave you a very clear picture about Nijinsky as notator - I would like to add: as choreographer... During the last years, my additional interest based on our joint work on restoring Faune has been to see Nijinsky's original score in the context of notational practices in the Ballets Russes (Fokine, Nijinska... and before...) and their specific (conceptual as well as praxeological) perspectives on movement - in Nijinsky's case this perspective is a musical one and his use of Debussy's partition (which one has been available?) deserves a closer look and comparison with his own practice of 'notating dancing musicality'.

AM3. How much leeway (if any) is there for individuality within Nijinsky's version?

AHG3. Leeway for individuality within Nijinsky's version can be compared with a musician's rendition of a music score. The correct notes are performed but there is dynamic leeway and also subtle movement timing within the music phrase. Such subtle timing variations can occur without losing the appropriate relationship to the music.

In Nijinsky's unfolding story we see two late nymphs enter, with heads bowed. They pull themselves together and ease into their appropriate places with an “alert” head, ready to take their part in the ritual. (See below in my response to question 7.) We see the Joyful nymph get inattentive and wander off, the others join her, they then apologize, bended knees and bowed heads. They then come back, with “alert” heads to perform dutifully their role in the ritual.

AM4. Nijinsky's 2-D bas-relief choreography involves what I clumsily call a zigzag use of the stage, so that the dancers move in horizontal or nearly horizontal paths. How far off strict horizontal does the notation allow the dancers to travel?

AHG4. All travelling is toward stage right or stage left, Nijinsky's stage indications being 4 and 12. Occasionally there was a 3 or an 11 indicated and we found these occurred when the nymphs or the faun needed to pass one another, so they veered slightly downstage or upstage while the body still faced 4 or 12.

AM5. How hard or easy is it to adapt the choreography to smaller or larger stages? Does Nijinsky indicate that some things should happen on or near the center line? What other geometries if any does he require and how are they to be fitted within different stage spaces?

AHG5. When a stage is too wide it has to be made narrower with black wings, otherwise the dancers would have to take giant steps. Nijinsky did not indicate in each case exactly where certain moments should happen. He provided only a few floor plans, this was a disadvantage for us. We were able to work out the spacing from the unfolding of the story, which moments had to be clearly seen by the audience, where the dress (the last veil) had to be dropped to allow appropriate spacing for what came next.

AM6. The chief nymph looks out front before dropping the first two veils . Is this, her look out front, notated?

AHG6. The only times the leading nymphs looks straight out front, as she displays the veils, was clearly stated by Nijinsky.

AM7. And is the use of eyes and head notated elsewhere in the ballet? If so, does the notation indicate what the dancer should look at or just in which direction?

AHG7. The head inclinations and rotations are clearly notated by Nijinsky. When the dancers should have an “alert head” (our term) this vertical lifting and elongating the neck was indicated by Nijinsky. He did not give indications for the eyes, but in his Russian notations alongside the movement notation he stated instructions such as “Looks at the grapes”. When the faun runs to and fro and pauses in between, he wrote “Laughs like an animal.” These verbal instructions fitted exactly with the movement notation at that point.

AM8. How precise or imprecise is the notation for the upper body and arms?

AHG8. If you look at the book Nijinsky's Faune Restored, pages 24-28, you will find examples of his different arm positions, the curve of the wrist, the curve of the hand. the contact of the fingertips. He specifically indicated a sequential lowering of the arms for the supporting nymphs at certain points.

He indicates inclinations in different directions for the whole torso, for the chest. In his notation he achieves a diagonally back torso contraction in which the shoulder and hip on one side draw together.

AM9. The 2-D bas-relief use of the body and head is a famous part of the choreography, but at what points does the choreography depart from it? The moment when the chief nymph drops her first veils seems to be one, at least with her upper body.

AHG 9. No, that does not happen when she drops the veils, not in Nijinsky’s score. But, after she drops the dress and goes to pick it up, she reverts to normal usage of the torso, until she wraps the dress across her and moves toward the faun.

AM9. So is the final moment when the Faune turns his body to address the veil; there, at last, he turns torso and legs to face the veil.

AHG 9. Yes, that is definitely true here.

AM9. Are there other moments when this 2-D body language is broken/ dropped?

AHG9. In the main, all performers adhere to the bas-relief torso stance.

When the chief nymph drops her dress, she looks at the departing two nymphs (frightened off by the faun) covers herself, looks down at the dress and three-dimensionally lowers to pick it up, looks again to the wing where the two nymphs have departed, then looks to the dress as she picks it up and arranges it in her arms as she walks toward the faun. Once the dress is arranged, she returns to the two-dimensional chest and head position.

It is in these more personal moments that the two-dimensional formality is dropped. As you noted, this occurs for the faun when he returns to the rock. In the Labanotation score this is shown by a change of key for directions. This change of keys is discussed in Appendix D.

AM10. Did you check the notation against the famous Nijinsky photographs? If so, did one always match the other? Or were there puzzles? (I’m always inclined to call the de Meyer photographs “studio” ones; I’m reminded by the scholar Andrew Foster that actually they were taken onstage at the Théâtre du Châtelet, but posed - action photos were very rare at that time.) Such photos, after all, may well not record stage choreography faithfully.

AHG10 Yes, we checked all available photographs including some that had never been published. Yes, they matched, with the exceptions of correct clothing, these differences are clearly described beneath each photo. Yes, they were studio photos and those mistakes were made, but the positions tallied with his score. Check out the photo section in the book, pages 57-70.

AM11. There is much debate about the ending of the ballet: orgasm etc. Can you say what help the notation is or isn't here?

AHG11. The sexy ending. Interestingly Nijinsky gave little detail for the ending. Claudia and I discussed what to do about it. We decided to use only what he had written. Thus the result is much simpler; most people are quite happy with it. The final release of tension says all that is needed. If people want histrionics they can go to the video of Nureyev's performance. Elizabeth Schooling, who taught it to the Joffrey company, said she could not stop him from putting in his own ideas and exaggerations. Elizabeth was 16 when Woizikovsky taught his version to the Rambert Company in 1931. Until we came along, she was the best and probably only source.

I do recommend that people read the front material in ourFaune book and also the appendices: you will find further information that will be of interest to you. We provided as much information as we could. Remember that this book was the result of many years of research work and we wanted to share it all with the dance world and future generations. I hope all this is helpful, thank you for your interest, they are good questions!

CJ. Ann, I think you have done a great job in answering Alastair’s questions.

As Ann does, I would also like to point to the FACT, that Nijinsky's notational skills respond to and equal his qualities as dancer and choreographer. And that (his) notating might be considered as an activity that needs conceptual and artistic decision - even more so when the choreographer/dancer creates his own system of notation in order to display his vision of dancing Faune.

AHG12. One strong point comes out. Nijinsky's musicality in this ballet can only be judged by his own written version. Remember that his notation makes use of music notes for timing, so that aspect is always very clear. The memory-based versions are not Nijinsky's choreography. They are the result of individuals' memory and preferences. Considering their timing could be an interesting discussion but you would not be discussing Nijinsky's timing.

Alastair, in your pre-seminar statement about what Claudia and I produce: “ ...their work with the notation has established a widely-used version of ‘Faune’ that they and others feel is definitive,” you are dismissing the fact that Nijinsky spent hours writing down this, his first ballet, and the result it there in the British Library for all to inspect. Anyone can check his original notation against our translation. What Claudia and I produce is what he wrote, no additions, no omissions. It is therefore the only authentic Nijinsky choreography.

We know that four years after Nijinsky created Faune, he was greatly upset in 1916 by how the choreography had already changed. We know this from the April 8th, 1916 New York Times. Quote: “Nijinsky's Objections to Diaghileff's Way of Performing His Ballet 'Faun' leads to its Withdrawal.” Nijinsky stated: “...the ballet 'The Afternoon of a Faun', should not be given as the organization (The Ballet Russe) is now presenting it. That ballet is entirely my own creation and it is not being done as I arranged it. I have nothing to say against the work of Mr. Massine, but the choreographic details of the various rôles are not being performed as I devised them. I therefore insist strongly to the organization that it was not fair to me to use my name as its author and continue to perform the work in a way that did not meet my ideas.”

I agree that a study of the many different memory-based versions can be very interesting, and people can have their favorite versions, but, as Nijinsky points out, none of these should be described as Choreography by Nijinsky. To do so is to dishonor the man and his intelligence.

CJ12. I would like to re-mention the artistic significance of Nijinsky's notated score as a document beyond taste and aesthetic preference. It is literal and visual and analytical at the same time and a document produced by himself revealing his concept of Faune by a highly developed notation system and a detailed score. This means for us: the notation is as valid for understanding his art and artistry as are the memories and embodiments of people who produced artistic responses to the inspiration that the event and other documents (de Meyer photographs, reviews etc) of his dancing have evoked.

AM 13. Would you like, for example, to say anything about how Nijinsky's choreography departs from the work of Fokine, Petipa, and others? What connections you see, if any, to Jeux and Sacre? And how does it anticipate the choreography of Nijinska, Balanchine, or others? I appreciate you may not feel those questions are your domain, but I'm interested if you are.

AHG13. The style of Nijinsky's choreography for Faune was such an obviously radical departure from what had been seen before; this has often been discussed. I personally have nothing to add in respect to that.

Once Nijinsky had made this breakthrough, he clearly felt free to make even greater departures in Sacre. Without doubt, Nijinska was greatly influenced in creating Les Noces, boldly departing from old familiar forms.

I see less direct influence on Balanchine's choreography, even when looking at the variation in styles that he used. But these discussions have not been part of my work and I have left it to others who are no doubt better equipped.

CJ 13. I agree with Ann - it is not just another version. And I do hope that Nijinsky's MANU-SCRIPT will be available (and evaluated) for further research on many levels.

AHG14: Alastair, I am still concerned that you (and others) speak about "Ann Hutchinson's staging", you do not seem to understand the difference between Pierre Lacotte's and Dina Bjorn's approach to working with old scores and Claudia’s and my research. They admit that they use the old material as a resource and then modify it to meet the tastes of today's audiences. I stick faithfully to the score, bringing it to life without any changes. I also take time, try out the results with students, take time to check details carefully. What Claudia and I produce is what Nijinsky wrote down, nothing changed, nothing added or left out. In working with his score every one of his symbols was transcribed into the equivalent Labanotation symbol. It was a painstaking task taking more than two years.

It would seem that you and others are reluctant to recognize that what we produce is the ballet as Nijinsky wanted it. I challenge you and others to learn his system and to check the Labanotation against his score. A good place to start would be the entrance of the three nymphs, meas. 21. The number of steps, the 3rd nymph pulling back on the 5th step. On the 7th step they stop, the first two turn their heads toward the 3rd nymph, the 3rd nymph turns her head toward them, they then turn their heads to look forward again, and all continue to walk. None of this occurs in the memory-based versions.

Because it is revived from Nijinsky's score, it is the only authentic version and this should be recognized. An evaluation of Nijinsky's musicality can only be based on this authentic version, all others were according to the individual's personal preference, Nureyev for example.

AM14: I understand your point about my calling it "your" version. The problem is simply that a few of those coming do, at present, prefer other versions and may challenge yours. You are working from Nijinsky's notation, but we have all seen dances staged from notation that either failed to bring the dance to theatrical life or that made questionable/wrong choices in the notation's ambiguous areas. Different stagers often make different choices from the same notation; and those differences can be the breath of life or the opposite. You may have got the original score to Beethoven's Fifth, but are you the conductor who makes it live?

Above all, I am not organizing a seminar to say “Here is the right Faune, staged by Ann and Claudia, and here are all these wrong ones, which you scholars may nonetheless prefer.” In most cases, those coming have never been able to see multiple Faunes in quick succession. The seminar is largely to help us open up the issues.

At least two of those coming, however, are scholars who have felt in the past that the differences between your version, however faithful to Nijinsky's intention, and some other stagings illustrates St Paul's words "The letter killeth; the spirit giveth life." I don't know whether they're right or wrong, and that's one important reason why I've organized the seminar. I hope you will accept that there may be grounds for argument. It would be lovely if your version makes everyone present feel that you have brought Nijinsky's photographs to life.

Still, two years ago I organized a seminar on Balanchine's Serenade, with films from the 1940s and 1950s, that showed everyone how very differently the same choreographer had kept reaccentuating the same ballet within the thirteen years 1940-1953 - all of them divergent from the ways he then staged it in later years - and nobody insisted that one version was more right than another, though the room included people who had been coached in it by Balanchine himself. It was a very successful seminar, which deepened everyone's love of the ballet. Likewise last year we had a seminar on Giselle, with people present who had investigated the Stepanov notation and other nineteenth-century records; we were all able to watch the films of Fonteyn, Markova, Ulanova, Spessivtseva and others as eager students prepared to enjoy their diversity. So here's hoping the same spirit will carry us through with Faune.

AHG: You are right, Alastair, it is not a competition and people have every right to their own preferences. In comparison to most memory-based versions, Nijinsky's original is mild, more gentle, a filigree work in which the nymphs are more human, they relate to each other. Two of them arrive late for the ritual; the Joyful Nymph gets inattentive and wanders off; these details are fascinating and they are absent from other versions. These and other subtle details are lost on the person looking for and wanting the histrionics that crept early on into the choreography.

Years ago, when notators taught a work from the score, we did not feel it was our job to be the dance equivalent to a music conductor. In time, we realized that we should take on this role. It is the performers who produce the theatrical result, with coaching from the dance director, who might also be the one teaching the work from a score. If that person has been a professional performer, so much the better. I return always to the comparison to music, they do not change the written notes, they find a way to bring it to life through the available aspects - a range of dynamics and leeway in durations.

In the case of Nijinsky's score there are no ambiguous areas in the notation. Concerning “differences between the 1912 original and your own realization”, people must realize that he wrote the score in 1915. How much it may have departed from the 1912 original, no one can say. We believe that he wrote it down as he remembered it. People should remember that he had over 100 hours of rehearsal when creating it which suggests very careful planning. We go by what he wrote in 1915.

I will be happy if people can understand why in 1916 Nijinsky was so upset by Massine's version of the faun, the statements he made then, and why, if we are to honor Nijinsky, we should be aware today of the points he made then.

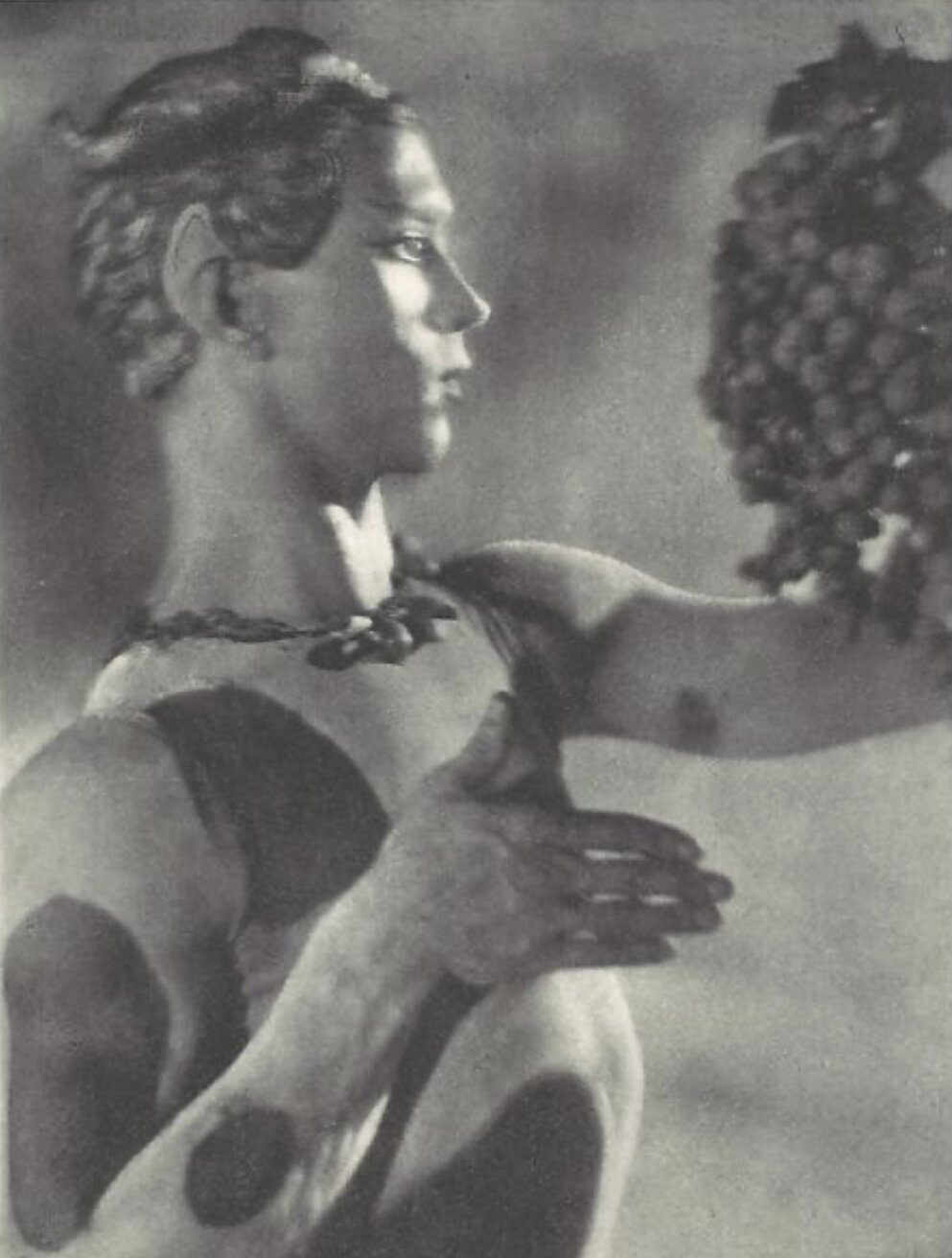

1: Vaslav Nijinsky as the faun in his 1912 “L’Après-midi d’un Faune”. Photograph by Adolf de Meyer.

2: Vaslav Nijinsky as the faun in his 1912 “L’Après-midi d’un Faune”. Photograph by Adolf de Meyer.

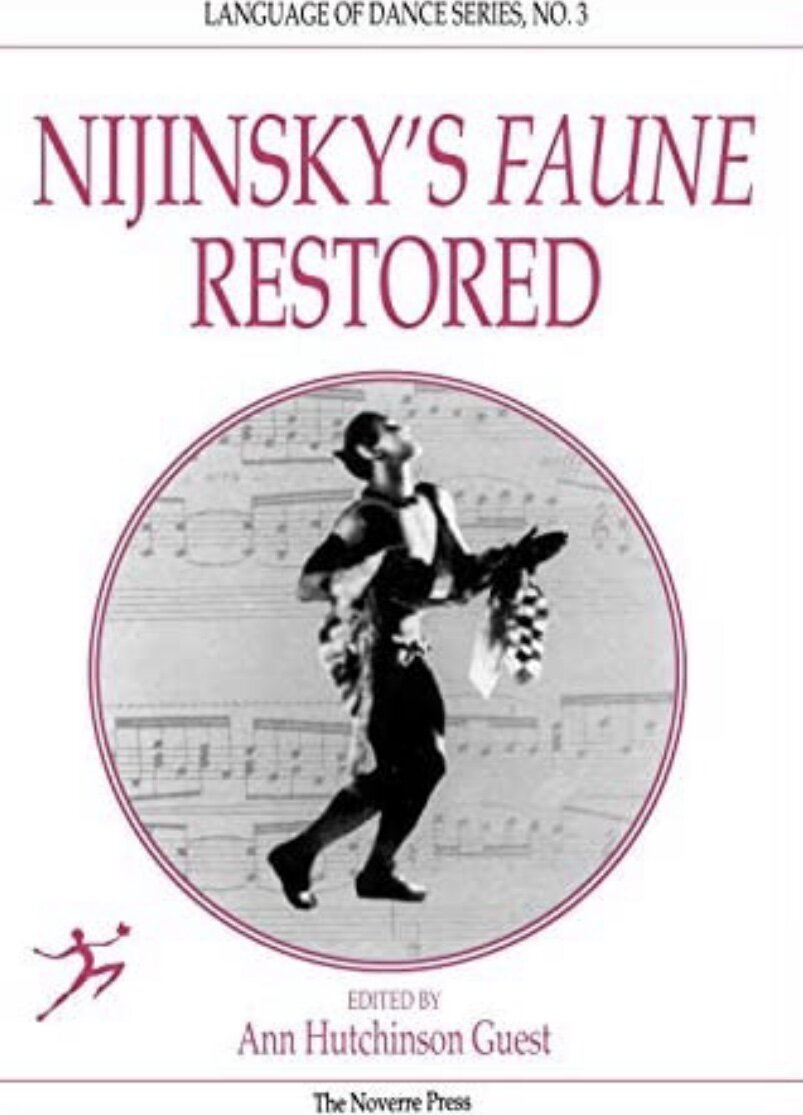

3: Cover of Ann Hutchinson Guest’s Noverre Press edition of Nijinsky’s notation of “L’Après-midi d’un Faune”.

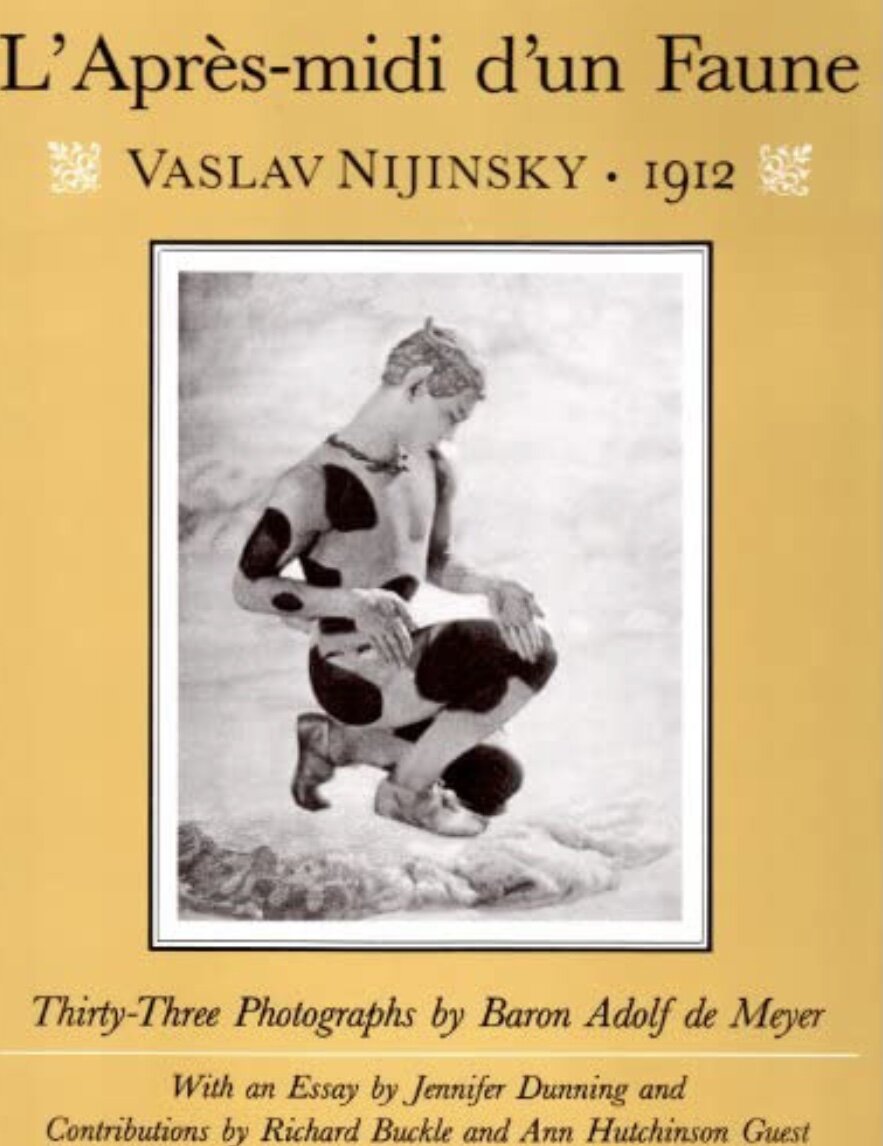

4: The Dance Books edition of Adolf de Meyer’s photographs of “L’Après-midi d’un faune”, with essay by Jennifer Dunning and contributions by Richard Buckle and Ann Hutchinson Guest

5: Faun and nymph: Lydia Nedilova and Vaslav Nijinsky, 1912, in Nijinsky‘s “L’Après-midi d’un faune”. Photograph: Adolf de Meyer.

6: Vaslav Nijinsky in the final sequence of his “L’Après-midi d’un faune”, 1912. Photograph: Adolf de Meyer.