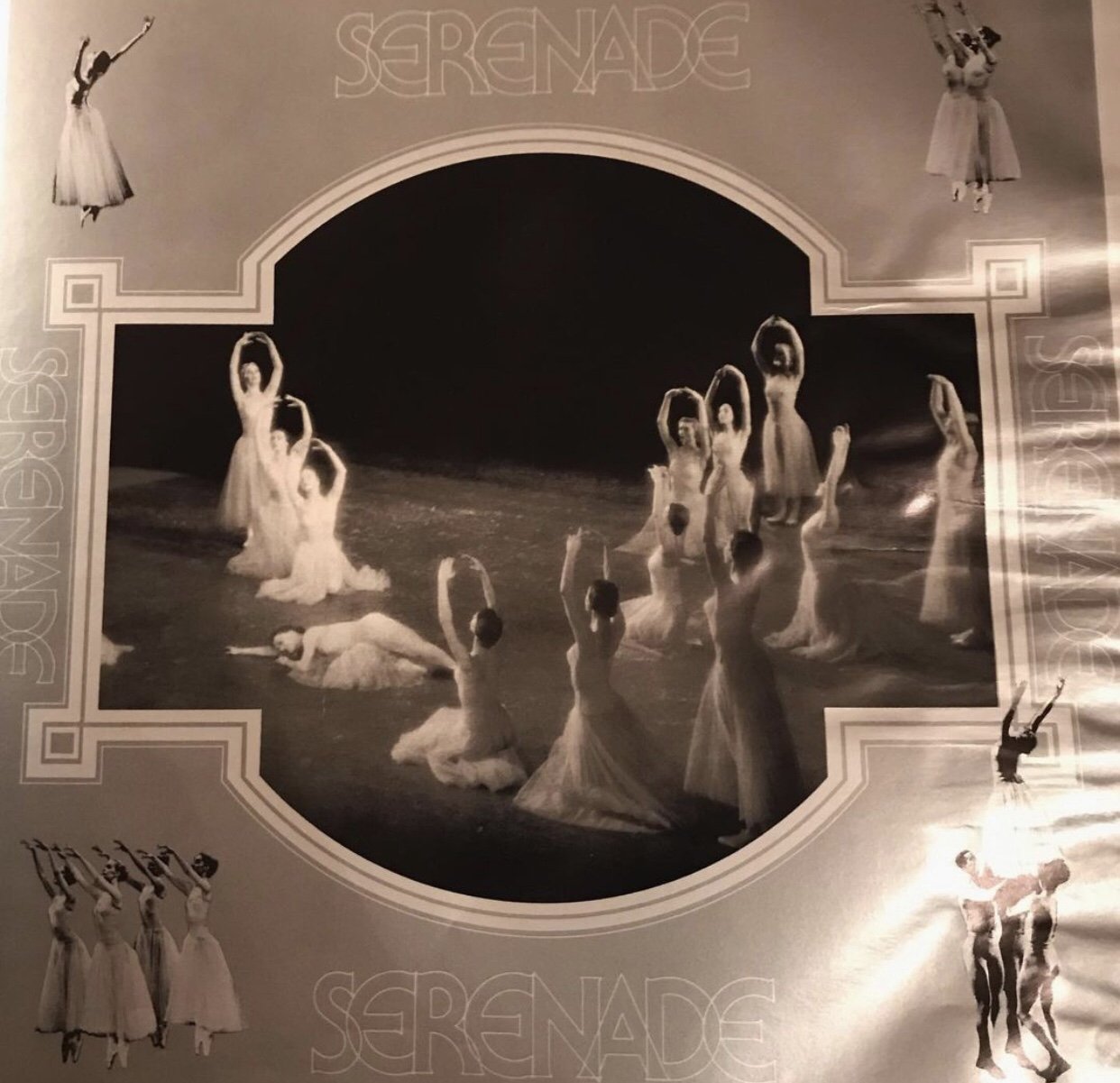

The genesis of Balanchine’s “Serenade”: a chronology and bibliography

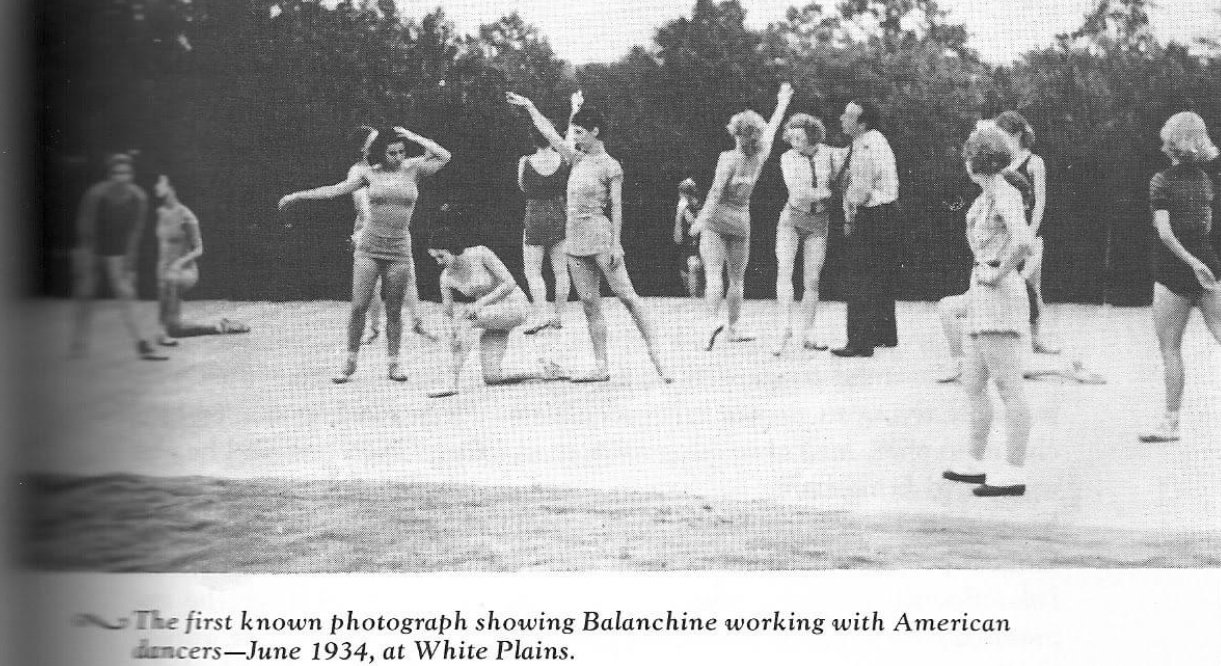

Jim Steichen’s generous contributions, based on his research toward his forthcoming book on Balanchine’s first ten years in America, have been crucial for the years 1934-35.

An earlier version of this essay was published in 2016 in Ballet Review as Serenade - a chronological list of evolutionary changes and a bibliography.

George Balanchine was known, even notorious, for the many changes he made to his ballets over the years. Even by his own standards, however, the revisions he made to Serenade are exceptional. Since the 1950s, it’s been known as a romantically classical work with its women in long dresses and with continuity between the four movements. Until 1950, however, it went through successive productions, all with women in skirts ending at the knee or above it; until 1940, it used only the first three movements of its four-movement score and presented them as isolated entities. In 1976, he made the women of the Elegy (the music’s third movement, presented by Balanchine as its finale) perform it with loosened hair: this wasn’t the first time he had tried something along these lines, but it remains controversial among those who remember it with hair bound.

Later, Balanchine liked to speak as if he had been gradually pursuing a single goal with this work. Evidence, however, shows how his idea of this ballet changed. Likewise the importance of Serenade itself to him developed considerably. And he repeatedly revised what he thought Tchaikovsky’s music was telling him.

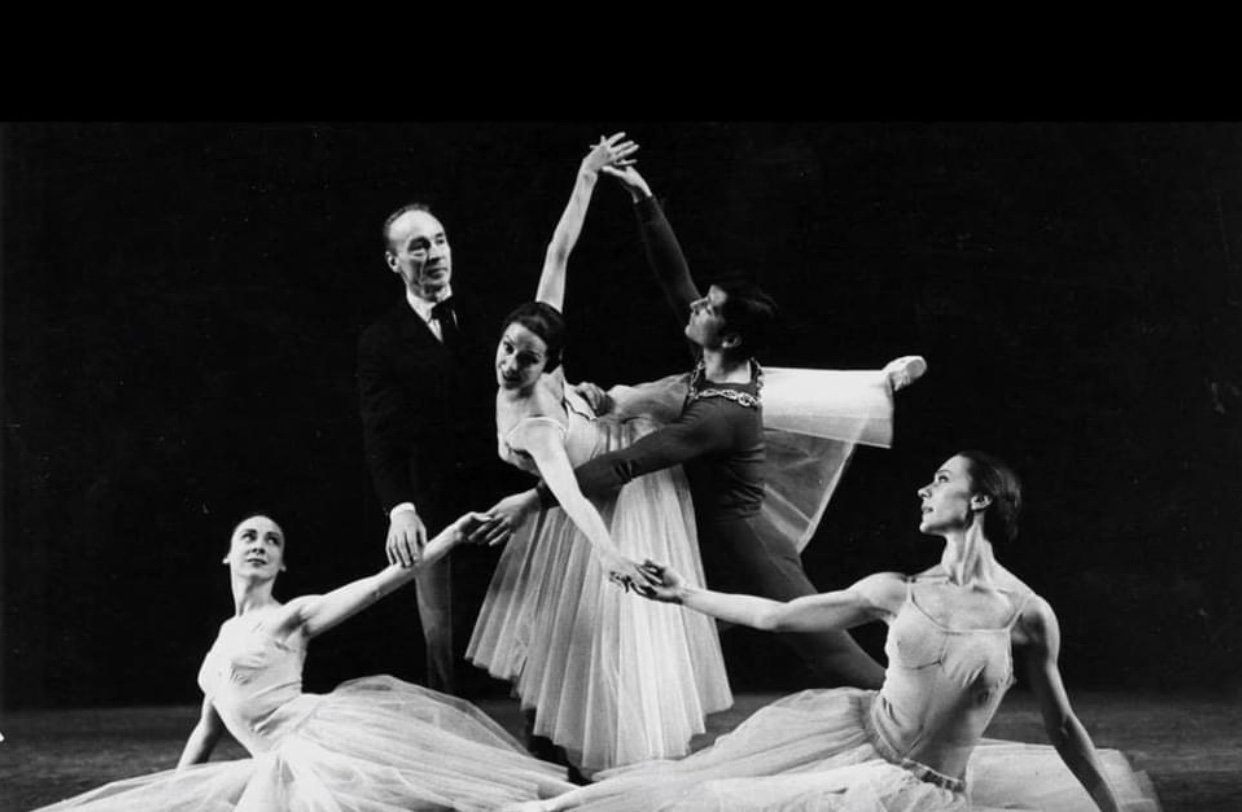

On August 26-28, 2015, I convened a three-day seminar on multiple aspects of this ballet at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts; I thank Jan Schmidt, director of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division. The seminar was filmed for the Library for the Performing Arts by François Bernadi. Silent film clips from Serenade performances in 1940 and 1944 (both Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo), 1951 and 1953 (both New York City Ballet) were shown, each in a different set of costumes; and photographs of Serenade from 1934 onward. It was administrated by Daisy Pommer, head of dance films for the Library. Present were Mindy Aloff, Jared Angle, Paul Boos, Holly Brubach, Vida Brown, John Goodman, Susan Gluck Pappajohn, Nancy Goldner, John Goodman, Robert Greskovic, Elizabeth Kendall, Allegra Kent, Simon Morrison, Gwyneth Muller, Kyra Nichols Gray, Claudia Roth Pierpont, Robert Pierpont, Nancy Reynolds, Suki Schorer, Victoria Simon, Jim Steichen, Carol Sumner, David Vaughan, Joy Williams Brown, most of whom contributed. (Robert Greskovic and Suki Schorer were especially instrumental.) On March 24, 2016, Robert Greskovic and I presented an evening of rare films and illustrations of Serenade at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts’s Bruno Walter Auditorium, Lincoln Center.

This chronology and bibliography arose from these sessions. In addition to the above names, assistance via email was given by Toni Bentley, Amy Bordy, Maria Calegari, John Clifford, Arlene Croce, Suzanne Farrell, Emily Hite, Susan Hendl, Amanda Hunter, Nicholas Jenkins, Deborah Jowitt, Elizabeth Kattner-Ulrich, Nancy Lassalle, Andrew Litton, Pat McBride Lousada, Barbara Milberg Fisher, Kay Mazzo, Colleen Neary Christensen, Susan Pilarre, Anne Polajenko, Daniel Pratt, Francia Russell, Sharon Skeel, and Alice Standin. Nancy Lassalle, Pat McBride Lousada, and Barbara Milberg Fisher were all valued friends who have since died; I honour their memory.

Further conclusions on Serenade and other Balanchine ballets are to be found in my 2021 essay for Liberties vol. 1 no 2, “Balanchine’s Plot.” AM.

1934.

1.Rehearsals begin on Wednesday, 14 March at School of American Ballet (637, Madison Avenue) in New York.

(What edition of the score was used? A copy of the piano rehearsal score, reflecting changes made at New York City Ballet in and probably before the 1960s, shows, among other things, two bars at the end of the Sonatina that are in no edition now known.)

According to Lincoln Kirstein’s handwritten diary for March 14:

“Balanchine doing new things to Errante. Started working on Serenade to Tchaikovsky’s music. He said his head was a blank & asked me to pray for him. He lined every one up according to their heights & commenced slowly to compose a hymn to ward off the sun.” (It’s possible that Kirstein wrote “a hymn to ward off the sin”; he may also follow “sin/sun” with an unquote mark as if ending a quotation from Balanchine’s own words. Most readers, including some who knew Kirstein and his handwriting, agree the word looks like “sun.”) “He tried two dancers breaking the composition, first in toe-shoes, then without; without won. The gestures of the arms and hands already seemed to me to have Balanchine’s creative quality. When I ebulliently suggested this to Dimitriew, he said je ne sais pas, dampening my too excessive and ready admiration…” (Kirstein, handwritten diaries, New York Public Library. Quoted by permission.)

There are several subsequent versions of Kirstein’s diaries, however. A typed transcript of the handwritten diary – very probably typed by Kirstein himself in later years, making significant omissions and emendations throughout – has the following:

“Balanchine doing new things to ERRANTE. Started working on SERENADE to Tchaikovsky string-music. He said his head was a blank and asked me to pray for him. He lined everyone up according to their heights and commenced slowly to compose a hymn to ward off sin. He tried two dancers breaking the composition, first in toe-shoes, then without; without won. The gestures of the arms and hands already seemed to me to have Balanchine's creative quality. When I ebulliently suggested this to Dimitriew, he said ‘Je ne sais pas,’ dampening my too excessive and ready enthusiasm....” (Kirstein, typescript diaries, same box, New York Public Library. Quoted by permission.)

Kirstein adapts that in the 1970s for publication as follows:

“Work started on our first ballet at an evening ‘rehearsal class.’ Balanchine said his brain was blank and bid me pray for him. He lined up all the girls and slowly commenced to compose, as he said – ‘a hymn to ward off sin.’ He tried two dancers, first in bare feet, then in toe shoes. Gestures of arms and hands already seemed to indicate his special quality. When I reported this to Dimitriew in his office, he growled: ‘Je ne sais rien du tout,’ calculated to crush my too ready approval.” (Kirstein, New York City Ballet, Thirty Years, p.37.)

(The next sentence of the handwritten original has Danilova, then visiting New York, saying that Holly Howard is already better than Toumanova in Mozartiana. The day ends with Kirstein writing about Martha Graham for The New Republic.)

Kirstein’s handwritten account, written on or immediately after the first day of rehearsals, should be compared with the much later memories of Balanchine (see 7) and Ruthanna Boris (see 9). It should be noted, however, that Kirstein’s point (New York City Ballet, Thirty Years, p.37) about the evening rehearsal is a later addition. Boris (see 9) remembers the opening rehearsal as taking place in the morning.

Kirstein in each version is brisk about how Balanchine lined up the women, whereas to Balanchine ( see 7) and Boris (see 9) – both writing later - this was of crucial importance.

2. Alternative versions of the ballet’s inception have been given. Jim Steichen writes:

“In fact, Serenade may have begun even earlier. Arnold Haskell’s Balletomania, written almost literally as the paint was still drying on the new studios of the School for American Ballet in New York, makes a possible reference to Serenade, noting at the close of an interview, conducted in 12 January 1934, that Balanchine ‘is already hard at work, creating a repertoire, the first work in which is to be an homage to his beloved classicism.’

“Ruthanna Boris, one of Balanchine’s first students at the School of American Ballet and one of his first important American dancers, maintains in her recollections of the ballet’s creation that it had already begun to take shape in late 1933.”

(Steichen, The Stories of Serenade: Nonprofit History and George Balanchine’s “First Ballet in America,” p. 10, James Steichen Working Paper #46, Spring 2012 http://www.princeton.edu/~artspol/workpap/WP46-Steichen.pdf)

Nonetheless, Steichen now disputes both Haskell’s and Boris’s assertions. Kirstein’s unpublished original diaries surely establish the March 14 date of the first rehearsal.

3. Kirstein later writes:

“While the purpose was certainly eventual performance, no date was set; we were all too occupied with day-to-day maintenance to consider any definite time for public exposure.” (New York City Ballet; Thirty Years, p.38)

The handwritten originals of Kirstein’s unpublished diary suggest that Balanchine may well have completed a first draft of the choreography for Serenade before March 29. (See 6.) Certainly, having begun with the Sonatina, Balanchine is at work on the Elegy on March 26 and admits many to watch a rehearsal on March 29. If so, he nonetheless made revisions almost up to the June 10 premiere.

4. What strikes Kirstein in his March 14 diary is gesture. By this, he recognizes the “creative” or “special” quality of Balanchine.

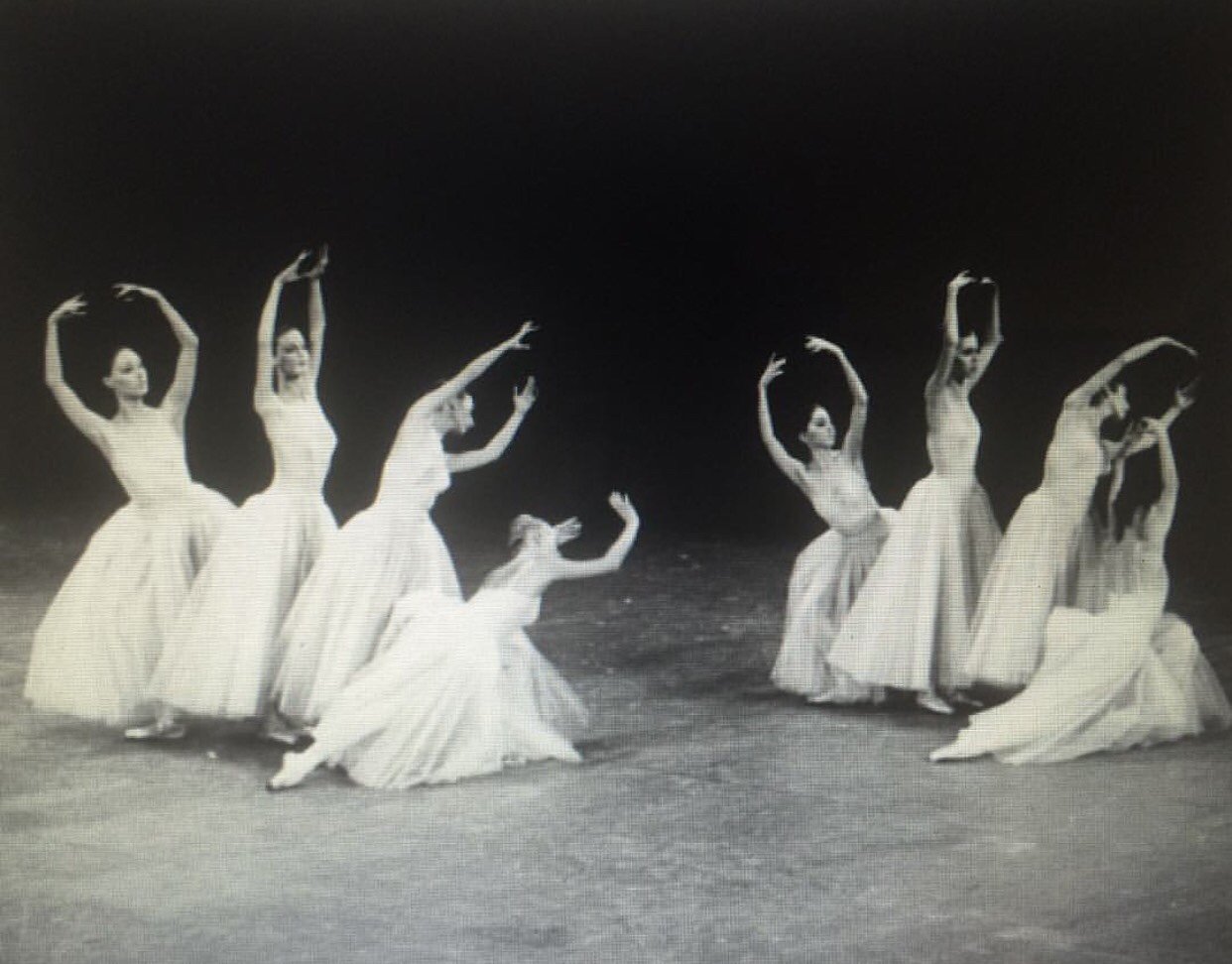

The opening ritual of Serenade, as has been often observed, transforms its seventeen young female dancers from women into turned-out classical dancers. Its nine stages - moving from that raised hand down to the feet, and, finally, opening up the whole body - approximately reflect the music’s descending scales. (For Ruthanna Boris’s description, see 9.)

If the opening gesture was part of “a hymn to ward off the sun” (“sun” rather than “sin”), then this is part of a long tradition of interpreting the opening gestures as a way of screening the eyes from the light. Later – we cannot ascertain the date - the light is seen as moonlight.

The second movement is the bend of the wrist. This has been analyzed variously. Carol Sumner (email March 16, 2016) says “it is not just a flick of the wrist; the elbow bends at the same time that the hand drops – but the hand is reacting to what it had to do to shield the eyes from the sun, and this move initiates the next one. It feels logical, natural – it’s real life, done within the meter of the music.” Suki Schorer (Serenade seminar, August 27, 2015) teaches a slight lift of the wrist and forearm while the hand drops. Victoria Simon (Serenade seminar, same date) says that the action is “a breath”: the initial breath that brings the ballet into life: with which Schorer strongly agrees.

The third is a slow port de bras (Allegra Kent, demonstrating this at the Serenade seminar, August 27, 2015, says “It’s like ‘The air is heavy’”) that ends by placing the wrist on the forehead. The fourth brings that arm down to cross the chest, the hand now resting at the base of the neck. The fifth is bras bas.

The sixth stage is the turnout of the feet into first position: of which Martha Graham said that it filled her eyes with tears: “It was simplicity itself, but the simplicity of a very great master – one who, we know, will later on be just as intricate as he pleases.” (Taper, Balanchine, p. 169). It is not known when Graham first saw Serenade, though it may well have been the March 1935 season of the American Ballet (she attended this, as Kirstein’s diaries show, but she may have missed Serenade). She probably spoke of it to Taper when relations between Balanchine and herself were at their friendliest, around 1959, the time of Episodes.

The seventh is tendu battement side (with arms opening from first to second); the eighth has the legs and feet closing in fifth position (with arms lowering to fifth en bas): the tendu and fifth position are the two most crucial items of Balanchine ballet style. (The five women of the Russian dance begin by closing in fifth position.)

The ninth, and last, is a port de bras opening through first to second position, with the palms turning and the head lifting (a backward bend of the neck and topmost spine) so that the face, arms, and hands address the sky. This uplift of face and arms to the heavens is another of the images that suggest a religious quality (see 12).

Almost all these stages become thematic material that returns during the course of the ballet. No formal turned-out first position, however, recurs.

5. As the ballet has been seen since 1966, this ritual returns twice more, each time when the music echoes the opening of the Sonatina with those descending scales.

In the first, at the Sonatina’s end, the “Waltz” heroine repeats the ritual as far as bras bas. According to Ruthanna Boris (though her account may not be reliable here – see 10), this was part of the original 1934 choreography.

The ritual’s second return is in the Tema Russo. When Balanchine first added the Tema Russo in 1940 (see 79), he did so initially with two musical cuts, one of which included this musical sequence. Only when he opened those musical cuts in 1966 (see 122) did he choreograph the final recapitulation of the ballet’s opening ritual and formation.

6. How did Balanchine end the Sonatina? The City Ballet piano rehearsal score shows its final two bars of the Sonatina has been penciled out, because they correspond to no known edition. Balanchine until 1966 also penciled out the loud, sharp ffz chord with which the Sonatina usually ends (unless this was a post-1934 change). He also made a diminuendo to the previous bar. This had the merit, as conductor Andrew Litton pointed out (correspondence, January-March 2019) of making a smoother transition from the Sonatina to the Waltz. But in 1934 there was no man in the Sonatina or Waltz; and the Sonatina may have ended with the latecomer completing the ritual phrase; also the Waltz was a separate scene.

Kirstein’s handwritten diary entries for March 14-29 - the period when probably most of the ballet’s 1934 choreography was made - include these entries:

“<March> 15. At rehearsal, Serenade progressed a few bars. In it, I see traces of arms as in Mozartiana and groups from Errante.

“<March> 16. …Balanchine didn’t want anyone to see Serenade yet; impasse.…

“<March> 20. …Blue material arrived for the school’s costumes. Rehearsals of ‘Serenade’ proceed…. A part in ‘Serenade’ where they get on their knees. The girls complained. B. said when he was composing Fils Prodigue for Lifar, he was on his knees for two weeks…..

“<March> 21. Watching Balanchine creating Serenade: Dimitriew & he had a row over G.B. giving so much attention to Marie Jeanne Pelus, who on account of her age may not be allowed to dance at all. Serenade very interesting: as Dimitriew says - Balanchine has now hit his stride and style; for years he was doing trick stuff hoping for surprise; something no one had ever done before. Now it was pure Balanchine. I see Errante & Mozartiana & Cotillion”<sic> “in it: figures even: but new uses of lines: new languor: new Romance. Also Balanchine is pleased with our progress. D. said three wks ago he felt it was a crisis: students dropping off: but now even de Basil & the Monte Carlo co. doesn’t phase him: Only he will show nothing to managers until we have four ballets: he is in no hurry. He knows we’ll be safe.” (Kirstein, handwritten diaries, New York Public Library. Quoted by permission.)

Marie-Jeanne Pelus (1920-2007) is thirteen at the time of these Serenade rehearsals. In the 1940s, after dropping the name Pelus, she becomes celebrated as Marie-Jeanne, creating the ballerina roles in the revised 1940 Serenade (see 54, 77-78, 88), Concerto Barocco, Ballet Imperial, and other Balanchine ballets. She danced in successive editions of Serenade until 1948 (see 105).

“<March> 22. … ‘Serenade’ is coming along. I recognize its sources in Errante and Mozartiana. Alfred and Marge Barr to rehearsal. Unresponsive and intelligent….

“<March> 26… Madame Riabouchinska to rehearsal of Serenade which has now a wonderful pas de trois of Heidi Vossler,<sic> Chas Laskey and Maloney. She said she cdn’t believe Balanchine cd. do anything so tender….

NB: This evidently describes the Elegy. Was Balanchine basing it on the Elegy in Fokine’s “Eros” to the same music?

“<March> 28… ‘Serenade’ considerably changed.…

“<March> 29. …Enormous crowd of people invited to see Rehearsal:… Dim. furious at the onrush wdn’t let us go through to see Mozartiana…. I was so nervous of Dimitriew’s displeasure I cd. derive no pleasure from ‘Serenade’, changed & improved.” (Lincoln Kirstein handwritten unpublished diaries, New York Public Library. Quoted by permission.)

7. Balanchine, however, later speaks of the first rehearsal as if the operative factor is not gesture but the number of girls present: seventeen. (Gesture, as he told the story, is the next issue.) In Balanchine’s Complete Stories of the Great Ballets, he (or Francis Mason on his behalf) writes:

“Soon after my arrival in America, Lincoln Kirstein, Edward M. Warburg, and I opened the School of American Ballet in New York. As part of the school curriculum, I started an evening ballet class in stage technique, to give students some idea of how dancing on stage differs from classwork. Serenade evolved from the lessons I gave.

“It seemed to me that the best way to make students aware of stage technique was to give them something new to dance, something they had never seen before. I chose Tchaikovsky’s Serenade to work with. The class contained, the first night, seventeen girls and no boys. The problem was, how to arrange this odd number of girls so that they would look interesting. I placed them on diagonal lines and decided that the hands should move first to give the girls practice.

“That was how Serenade began. The next class contained only nine girls; the third, six. I choreographed to the music with the pupils I happened to have at the time. Boys began to attend the class and they were worked into the pattern. One day, when all the girls rushed off the floor area we were using as a stage, one of the girls fell and began to cry. I told the pianist to keep on playing and kept this bit in the dance. Another day, one of the girls was late for class, so I left that in too.

“Later, when we staged Serenade, everything was revised. The girls who couldn’t dance well were kept out of the more difficult parts; I elaborated on the small accidental bits I had included in class and made the whole more dramatic, more theatrical, synchronizing it to the music with additional movement, but always using the little things that might ordinarily be overlooked.

“I’ve gone into a little detail about Serenade because many people think there is a concealed story in the ballet. There is not. There are, simply, dancers in motion to a beautiful piece of music. The only story is the music’s story, a serenade, a dance, if you like, in the light of the moon.”

(But see 96, 120, and 128 for what he said on later occasions about stories within Serenade.)

The two-part Dance in America TV documentary Balanchine (1984) includes a film clip in which Balanchine says that he was just making dances to show his new American dancers how to perform onstage.

In an account written decades later, Ruthanna Boris remembers Balanchine starting with the opening formation we see today; she provides a diagram to show how she and Annabelle Lyon, the shortest girls, were placed at the front. (Reading Dance, edited by Robert Gottlieb, pp.1063-69.)

Certainly Balanchine and Kirstein confirm that he worked on the 1934 Serenade in a way that he seems never to have used so pointedly before or again, incorporating the chance events of rehearsals: the girl who falls over (see 29); the day only nine girls turned up (Kirstein, Thirty Years, p. 38); the girl who arrives late (Leda Anchutina according to Kirstein, p.38; Annabelle Lyon according to herself and Ruthanna Boris– see 31); the first man who arrives by himself; the four men who arrive together one day.

Balanchine pointedly says that nine girls came one day, six the next. It may or may not be relevant that the Sonatina, as we now see it, has an early incident in which two separate groups of nine and six girls are played antiphonally against each other.

8. The ballet begins with seventeen women. Balanchine said, “I happened to, I have seventeen dancers. And I placed them, almost looks like orange groves in California, you know? If I had only sixteen, even amount, there would be two lines. And now people ask me, why do you place them that way? Because I have seventeen.” (1984 documentary Balanchine, Production of Thirteen/WNET New York, Produced by Judy Kinberg, Directed by Merrill Brockway, Written by Holly Brubach, West Long Branch, NJ: Kultur, 2004. Quoted by Jim Steichen. The Stories of Serenade: Nonprofit History and George Balanchine’s “First Ballet in America,” p. 10, James Steichen Working Paper #46, Spring 2012 http://www.princeton.edu/~artspol/workpap/WP46-Steichen.pdf)

Balanchine, however, had not yet been to California. So this may be one of many wise-after-the-event stories in the histories of himself and this ballet.

9. Ruthanna Boris (1918-2007), writing several decades later, recalls that Balanchine, at the first rehearsal, Balanchine - after announcing “we will make some steps” and creating the opening formation - started not with a gesture but by speaking to the seventeen women of his life in Russia (“It was revolution, bullets in street”) and his move to Europe:

“Little by little his talking became more and more like a report—less conversational, more charged with feelings of anger and distress: “In Germany there is an awful man - terrible, awful man! He looks like me only he has mustache - he is very bad man— he has moustache – I do not have moustache – I am not bad man – I am not awful man!’… It seemed to me he was tasting his words and trying to get past them. To the best of my memory no one knew what he was talking about. We were adolescent and young ballet dancers, mostly American, mostly aware of the dance world, unaware of governmental affairs in the world beyond it….

“Suddenly he paused, fell silent, drew himself up and proclaimed, ‘When people in Germany see that man they do this’ – his right arm shot out in front of him, raised diagonally up toward the ceiling. He continued, speaking softly, leaving his arm exactly where it was ‘But you see, I am not bad man, I do not wear moustache – maybe for me, you do this.’ He moved his arm to the right side, still held in a right diagonal. His voice went on ‘Now put together feet, side by side – now, turn face, eyes look at hand. Now maybe hand is tired, hand falls down.’ His hand slowly relaxed its stiff salute, his finger-tips, then hand, then wrist softened and dropped until the wrist was completely bent, the hand suspended from it. He continued, ‘Now head is tired, cheek rests on left shoulder, wrist rests right side forehead, hand falls down, rests front of left shoulder, head change, rest on right shoulder, rests front of left shoulder, hand, arm fall down, meet left hand, make position preparation, feet make position one, arms position two, battement tendu par terre à la seconde, right foot, close position five front, arms again position preparation, and, we dance!’

“He had shown all the hand., cheek, head, and arm positions as he spoke them; we had picked up and moved along with him, just as we had been practicing to do in all our technique classes for all the months we had been working with him.”

Boris recalls that only then does Balanchine have the music played by the pianist Ariadna Mikeshna. “It did not go perfectly the first time we did it. We all realized there was much refining and polishing ahead, but! we were on our way…. We roughed out half the first movement that first morning, configuration after configuration for groups, small solo enchaînements interspersed between them, lots of running, weaving in and out between each other, sudden pictures made by interwoven arms, varieties of body level in relation to the floor, always moving, always connected in time and space.

“That night, as I lay in bed mentally rehearsing all I had learned in two one-hour rehearsals that morning, counting the ten-minute speech before the dancing began, the wonder of his way of making dancing filled me with a swelling sense of mystery. The words he had said, the image of an awful man with a moustache who looked like him transformed into an opening of sad reverie that became a dance of gracious connections and beauty! The dancing that seemed to pour out of him as he worked among us had reminded me of a spider spinning a web. I looked up at my bedroom ceiling, and said, ‘Whatever you are, wherever you may exist, you were with us in Studio A this morning. I want to understand why he said what he said and did when he did. Maybe sometime I will.’” (Reading Dance, edited by Robert Gottlieb, pp.1065-67)

This may be a conveniently elided account. By the time it was written, Balanchine had revised the ballet extensively several times; Boris herself had danced the leading role in 1944-46 performances (see 93-95). In her subsequent account of later rehearsals, she seems to misremember two points that evidence suggests occurred in neither 1934 or 1935. (See 31.) Her version not only includes much that Kirstein’s original diary entry omits (the reference to Hitler above all), it also omits the rehearsals of Errante and Mozartiana mentioned in Kirstein’s original diary. It is not, however, the only account of Serenade that links the opening gesture to Hitler; and Boris also spoke to both Mindy Aloff and Nancy Reynolds of Balanchine’s words about Hitler and the opening formation.

Some, plausibly, have seen a connection between the opening of Serenade and the German and American modern dance of the 1930s (German movement choirs, for example). It’s possible Balanchine, whose mind was turning to Hitler according to Boris, may have thought here of German group modern dance, though there is no firm evidence. We know that he wanted the Russian dance (Tema Russo), added in 1940, to have a modern-dance (probably Bennington) quality. See 79.

10. Despite Balanchine’s words about the music’s story being “a serenade, a dance, if you will, in the light of the moon,” Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings is often solemn and contains, especially in its Elegy, passages of considerable melancholy or anguish. No previous musical serenade (for example those by Mozart, Brahms, Dvorák) had contained such depth of feeling. Although Tchaikovsky began it in 1880, its first performance was given on April 30, 1881 (Old Style) in memory of the pianist Nikolai Rubinstein, Tchaikovsky’s close friend, who had died 11 March. (The first performance of the Serenade is often given as later that year, but Simon Morrison has recently discovered this in the unpublished notes of the Russian conductor Eduard Nápravnik.)

Aspects of both death and new life are often noted in Balanchine's Serenade choreography. Is this connected to his own recent tuberculosis in 1929-30? Kirstein's 1933-34 diaries several times mention other people's expectations that Balanchine has three years or one left to live. On March 16, four days after start of Serenade rehearsals, Kirstein takes Balanchine for a medical check-up. "With Bal. to Dr. Geyelin; thank God he is very much better than he was before, & may get absolutely cured. Gayelin said he could screw whomever he wished as long as he didn’t kiss them.” (Kirstein handwritten diaries. Quoted by permission.) "You know, I am really dead man," Balanchine told Ruthanna Boris later. "I was supposed to die, and I didn't, and so now everything I do is second chance." (Robert Gottlieb, Balanchine - The Ballet Maker, 2004, Harper Press, p. 58.)

11. Balanchine choreographs the first three movements of Tchaikovsky's Serenade for Strings music for the School of American Ballet: Sonatina, Waltz, Elegy.

He does not choreograph the final movement, the Tema Russo or Russian dance, until 1940. (See 79-82.) Since that contains several of the key images of Serenade - the five girls linked together at the start, the heroine and hero suddenly arriving from opposite sides to stop like stags with antlers locked, the heroine who falls spectacularly as the corps runs out - this is hard for us to imagine.

Probably (see 32) he choreographs the three movements as separate scenes without the through continuity that the ballet acquired in 1940 or earlier.

12. Although the words “hymn to ward off sin” may not be what Kirstein wrote in 1934 about the first day’s rehearsal of the ballet’s opening gesture, nobody has questioned it since he published it in 1973. If correct, it is the first of several suggestions of religious imagery in Serenade.

The opening ritual has a devotional quality, like nuns saying their vows; and the idea of a sorority like a religious collective may be felt at several later stages, right through to the Elegy’s final cortège at the ballet’s end. See also 4 (the end of the opening ritual), 14 and 39 (the Dark Angel beating her “wings”), 17 (the winged angel at Tchaikovsky’s grave), 20 (Orphic imagery), 41-44 (the ballet’s ending), and 133 (arms in prayer).

13. In using only the first three movement of Tchaikovsky’s four-movement Serenade, Balanchine is using the same music that Mikhail Fokine used in 1916 for Eros, a ballet that Balanchine must have seen in its 1922 Petrograd revival. (A negative account of its 1916 production is given by André Levinson in Ballets Old and New, pp. 92-93,)

14. There are other striking connections between Fokine’s Eros and Balanchine’s Serenade. Notable among these is how both works echoed the arrangement of figures struck by Antonio Canova for his Cupid and Psyche sculpture. Balanchine, in conversations in the late 1960s and early 1970s, confirms to John Clifford that he was alluding directly to the Canova Cupid and Psyche sculpture. (Clifford, email to Alastair Macaulay, May 14, 2016.) On August 28, 2015, both Elizabeth Kendall and Robert Greskovic spoke at length of Eros; Robert Greskovic returns to this (“Rare Films and Illustrations of Balanchine’s Serenade”) on March 24, 2016.

It may well strike Balanchine that this Canova statue, properly titled Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, recurs in the three cities most important to his career: St Petersburg, Paris, and now New York. The first (marble, 1787-91) has been in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, since 1824. The second (marble, 1794-99) has been in the Hermitage, St Petersburg, since the nineteenth century. The plaster model for the second, inherited by Canova’s favorite assistant, Adamo Tadolini, is in the Metropolitan Museum, New York. Cupid (or Eros), with wide wings, leans down toward Psyche, whose arms stretch up to circle his head while his descend to frame and embrace her upper torso; their faces come close for a kiss. This image occurred not only in Fokine’s original but also in subsequent revisions of it; Robert Greskovic shows (August 28, 2015, Serenade seminar, and March 24, 2016, “Rare Films and Illustrations of Balanchine’s Serenade”) a photograph of Galina Ulanova in this position with Mikhail Dudko, a male dancer who was Balanchine’s Mariinsky contemporary.

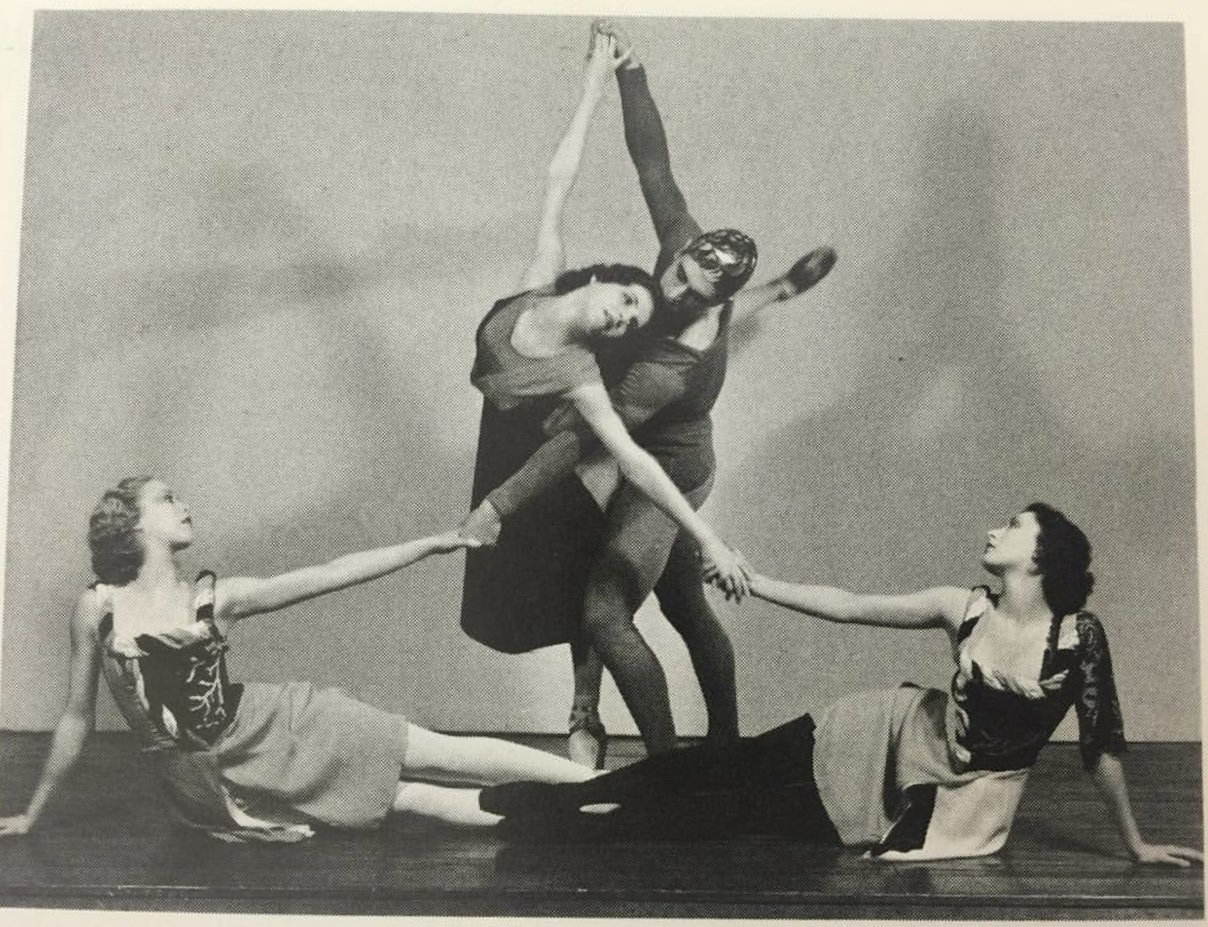

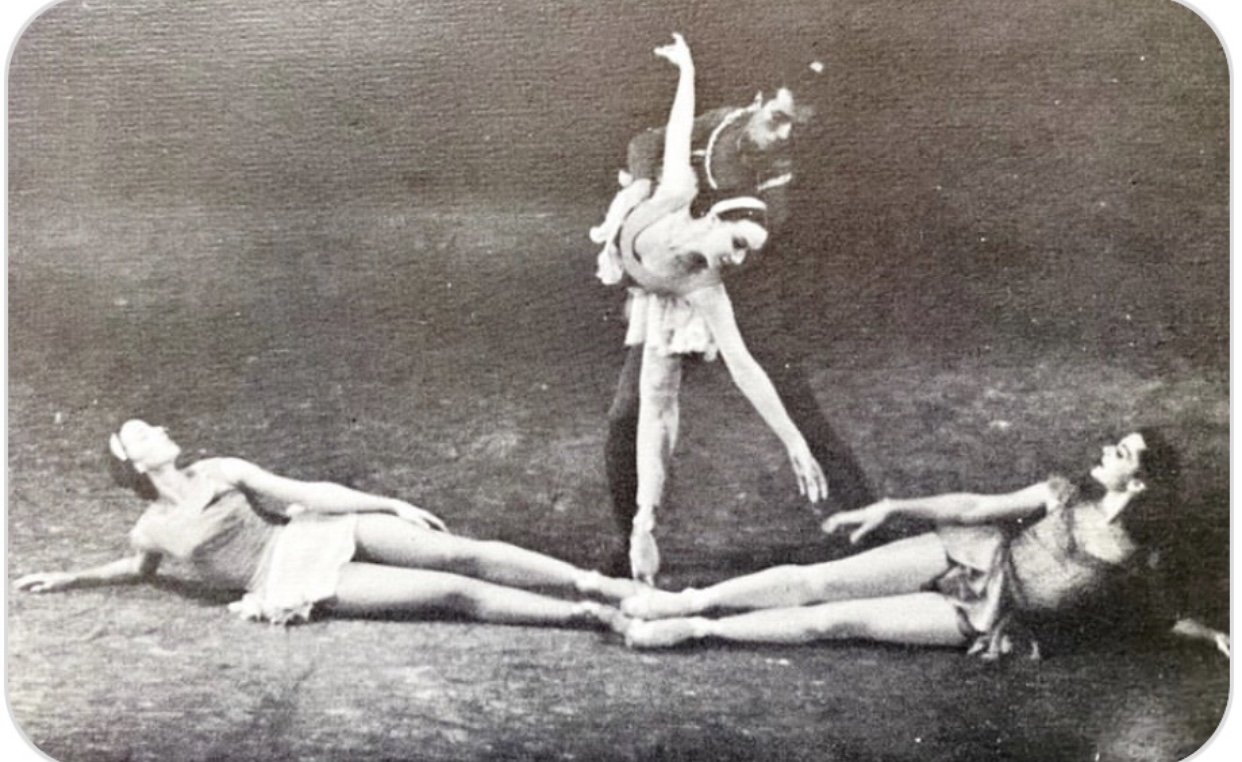

It is this “Canova” image that Balanchine uses in the Elegy of Serenade for the heroine, her male partner, and the female dancer often known as the Dark Angel. In the Balanchine’s Elegy, the Canova echo is strongest when the male dancer has his final farewell to the heroine, with the “Dark Angel,” her face unseen, close behind him and extending her arms like wings. (As he and the Dark Angel return to the vertical, she beats those “wings” three times – see 41, 102 - and, in the same rhythm, places one hand over his eyes to render him sightless and the other hand across his chest: the configuration in which they entered at the start of the Elegy.) In a pointed quotation of the Canova sculpture, the 1944 Ann Barzel film – see 94 – shows the heroine (Ruthanna Boris) rings her arms around the man’s (Nicholas Magallanes’s) neck and stretches up for a farewell kiss.

15. Parts of Fokine’s Eros scenario, as Elizabeth Kendall shows, are close to some of the other events in Serenade, notably its Elegy. The Romantic themes include love, fate, and dream; Fokine’s heroine near the end has a “waking from a dream” moment, which corresponds to the way the Elegy’s heroine rises from the floor after the man’s departure. It is important in the Serenade Elegy that, near the end, its heroine is lowered to lie on the same part of the floor on which she is found at its start (and, since 1940, on which she fell at the end of the Tema Russo).

Marcia Siegel: “She is back in the spot where she first fell. Seeing her there again, with the man hovering behind her, is like returning to the start of a flashback in a film. Now we seem to understand how she got to be there…” (The Shapes of Change, p.78)

This “flashback”-like quality may be derived from Eros. Eros also features a statue of the title deity. So does Balanchine’s 1947 Paris production of Serenade: see 99.

Elizabeth Kendall writes (Balanchine and the Lost Muse: Revolution & the Making of a Choreographer, Oxford University Press, 2013, p. 196) of Lidia (Lidochka, Lida) Ivanova in 1923 performances of Eros:

“In Fokine’s 1916 Eros, about a girl torn between the pagan girl and a Christian angel (the angel wins), Lidochka played one of nine nymphs dancing the traits of romantic love in front of the statue of Eros. Lida’s nymph was Jealousy…. The Eros nymphs danced to the sweeping waltz that would become Balanchine’s Serenade’s second movement (perhaps with the ghost of Lidochka still in it).”

16. There may be other Fokine connections. Kirstein (Thirty Years, p.38) notes that Fokine's Chopiniana (Les Sylphides) “derived from a situation corresponding to our own - schoolroom, or an academic recital projected toward repertory theater.”

Balanchine’s 1940 addition of the Tema Russo gives a specific echo of Les Sylphides (see 79) and of another Fokine device (see 81).

A central Balanchine device, evident at the start of Serenade, may well derive from Les Sylphides. The music begins and the curtain rises to reveal a tableau that remains motionless. Only on a particular moment in the music does the dancing begin. This remains Balanchine’s usual way of commencing a ballet for the rest of his career. Seldom does the curtain rise on dancers already in motion: in this respect, Allegro Brillante (1956) is a rare exception.

It’s also possible that Balanchine’s style in Serenade is influenced by the Russian choreographer Kasyan Goleizovsky (1892-1970). Balanchine mentions Goleizovsky as an example in early conversations with Kirstein. See, for example, Kirstein handwritten diaries, February 10, 1935.

17. Others, including Tim Scholl, also argue that the image of a winged angel behind the hero comes from Tchaikovsky’s grave. Robert Greskovic shows this image on August 28, 2015 (Serenade seminar) and March 24, 2016 (“Rare Films and Illustrations of Balanchine’s Serenade”).

Balanchine himself stresses in later years that he felt Tchaikovsky was with him throughout Serenade (“Almost the whole of Serenade is done with his help.” Balanchine in Solomon Volkov, Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky, p. 35.) This is said late in Balanchine’s life. It is not easy to reconcile it, however, with his many changes of mind about Serenade over the decades.

18. The possible connections of the Serenade Elegy to pathos, death, and the realm of the dead are complex. It is possible to feel that the heroine is already dead, like Eurydice, when the Dark Angel brings the Orpheus figure to her; or that she dies when he leaves her; or that she moves toward death at the very end.

Elizabeth Kendall suggests (Balanchine and the Lost Muse – Revolution & the Making of a Choreographer, 2013, pp. 10, 196, 234-6) that the Elegy’s heroine was inspired by the death by drowning of Balanchine’s friend and dance contemporary Lydia Ivanova, just at the time Balanchine was leaving Russia in 1924. This may also connect to the theme of water imagery that many find in several parts of Serenade. (At the end of the Sonatina, as the corps walks out across the stage, they hold their hands behind them. The image given to New York City Ballet dancers since the 1950s has consistently been “as if trailing your hands in the water”. Victoria Simon and Gwyneth Muller speak of this at the Serenade seminar, August 28, 2015.)

Kendall (referring to Balanchine as “Georges”) writes:

“He reversed the order of the last two of Tchaikovsky’s four movements, so the third, an elegy, comes at the end, and the ballet itself becomes an elegy. On the way to this elegy’s raison d’être, the dancers enact some scenes that seem peculiar and deliberate. A woman comes in late and tries to find her place in the corps de ballet. The same woman later trips and falls to the ground. (Both events really happened in rehearsal and went into the choreography.) A man enters after the girl has fall and walks toward her, with another girl hugging his back and shielding his eyes – so he won’t see the fallen girl? So he can’t help her? The two pause beside the fallen girl, and the walking girl, now hidden by the man, flaps her arms like wings to the music, as if giving wings to the fallen one. She and the man continue walking offstage, then the fallen girl gets up and runs to another tall dancer on the other side of the stage (as Giselle runs to her mother at the end of her mad scene). In her embrace, she slips down and is lowered to her knees. Has she died? She’s preparing, at any rate, for the next phase of her destiny, which will transpire in heaven.

“Here is the subject of Serenade’s elegy: another victim, another ballet corps like the one in Giselleor The Sleeping Beauty, or in Georges’s own Marche Funèbre for the Young Ballet. But the corpses in earlier ballets rise again to dance. Serenade’s corps doesn’t. She’s lifted instead sill in a standing position by four men who come onstage for this purpose, then carried across the stage into the upstage right wing. Her raised face meets a ray of light. A train of Serenade’s corps de ballet follow, their faces raised too, and arms raised forward in supplication.

“Is she Lidochka? Who can know? Whoever she is, she’s spared the indignity of being carried horizontally. She enters heaven vertically, in a ray of light, like the ray of light Lidochka once dies in onstage in Valse Triste. And Serenade’s music is the same that Fokine used for his ballet Eros, in which Lidochka danced so memorably… And all of Lidochka’s friends knew how she felt about Tchaikovsky. ‘Sometimes I would like to be one of the sounds created by Tchaikovsky,’ she once wrote on a picture for a fan, so that sounding softly and sadly, I could dissolve in the evening mist.’ In Serenade, she does that.” (Balanchine and the Lost Muse, pp.234-36.)

There are minor errors here. Kendall confuses the girl who fell in 1934 rehearsals with the heroine’s fall at the end of the 1940 Tema Russo. The Dark Angel in the Elegy surely shields the man’s eyes so that he will have no choice but to meet the woman to whom she is – temporarily - leading him. Allegra Kent (August 27, 2015) is among the Balanchine dancers who does not interpret the ballet as ending with death or heaven, though she does agree it is about a new phase of existence. Nonetheless Ivanova may well have been in Balanchine’s thoughts with this music.

19. Another death that may have affected Balanchine was that of the young Danish ballerina Elna Lassen. He spent a few months in late 1930 in Copenhagen, where his first choreography for the Royal Danish Ballet was to Liszt's Liebestraum (September 16, 1930, http://www.balanchine.org/balanchine/display_result.jsp?id=156&sid=&searchMethod=¤t=&stagings=&refs=1&tvs= per “100. [Duet and Trio],” Liszt, Liebestraum) . In this, Balanchine partnered Elna Jørgen-Jensen in a pas de deux, then danced with Elna Lassen and Ulla Poulsen in a pas de trois.

Poulsen speaks of the pas de trois in I Remember Balanchine:

“His own role was not very big. He had stopped dancing because of his health, but I know it was something that he loved. Liebestraum was about a man who loves two women, but one he loves more. I was the woman he was leaving behind. It was a very emotional piece. First, we were together, then he didn't know which one he wanted. The dance was more mime, not so much a pas de deux. He had come to the Danish ballet and found that we had much expression. So he managed to make ballets with mime and emotion, instead of the Russian style with the brilliant dancing, turns, lifts, and technical solos.... The only thing I couldn't do was a real Balanchine ballet, because I had weak feet.” (p.95)

It's startling to discover that Elna Lassen committed suicide only four days later: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elna_Lassen. Poulsen says:

“Elna Lassen was a beautiful dancer and a really fine person. She was very light, and she jumped very well. Balanchine was especially moved when she died, a suicide, to all our sorrow….At the special performance following <her> untimely death, Balanchine danced the male role in Chopiniana. It was the only time that he danced it. He knew the ballet from his years with Diaghilev, and I don't think he changed anything. It was performed only the one evening. He danced very beautifully. At all the points where Elna Lassen should have danced, the spotlight was empty.” (I Remember Balanchine, p. 95)

(Thus Balanchine anticipates the famous performance in 1931 after Pavlova's death at which they played The Dying Swan with just a spotlight to show her path across the stage.)

The 1930 Liebestraum pas de trois, about a man “who loves two women, but one he loves more” and leaves one behind, sounds like a distinct precedent for the Elegy in Serenade. The death by suicide of its dancer Elna Lassen may be a connection to the Elegy’s funerary quality.

20. The Elegy also offers ideas of ideas of sightlessness, fate, and the beloved heroine whom the man finds only to lose again. These may also derive from the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in the Underworld.

Kirstein’s unpublished diary entry for April 9, 1934, records Balanchine playing the music for Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice. (Kirstein uses the French title.) “Bal. playing over Gluck’s Orphée which he wants to do as an erotic ballet. Walked home to 350 East 53. Marvelous day & wrote out the lovely story from Bullfinch’s age of fable on Orpheus.”

Kirstein’s diaries for May 7, 13, and 14, 1934, mention Dimitriew’s concern that Balanchine is considering an Orpheus film with the composer Georges Antheil:

May 7. “…At the School, Dimitriew angry at Antheil & Bal. for considering doing a movie on ‘Orpheus’ in an amateur way, ruining Bal’s vacation & spoiling all our affairs….

May 13. “... (At the School) Dim. drew me aside : said that Salop Antheil had persuaded George B. to do the Orpheus film & if he did it it wd ruin his vacation - & our chances for ballets. Gt scene yesterday which I’m glad I missed, Bal. insisted he wd. do it. Dim. swore he wdn’t….

May 14. “…I spoke to Antheil abt. canning the film he & Bal. was going to do until later: he was confused, pleased that he'd always wanted to do a film & that the money was right at hand, & he cdn't help grabbing at it….” (Kirstein, handwritten original diary, New York Public Library. Quoted by permission.)

No such film happens, but Balanchine choreographs Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice at the Metropolitan Opera in 1936. Robert Greskovic (August 28, 2015; March 24, 2016) shows photographs from this production that show Eros with huge wings, Orpheus, and the recumbent Eurydice; a resemblance to the Elegy of Serenade is evident. (It’s worth stressing that Gluck places Eurydice among the Blessed Spirits in the Elysian Fields.)

Balanchine returns to the Orpheus myth throughout his career: notably in his 1936 staging of the opera, his 1948 Stravinsky ballet, and his 1976 Chaconne. In both Serenade and the 1948 Orpheus, a character is the Dark Angel: in Orpheus, that angel is male. (It happens that August Bournonville refers to the title character of La Sylphide as a “bad angel”. See My Theatre Life, p. 79.) Is the Serenade character known as “Dark Angel” because, though female, dancers recognize she serves a similar function (fateful, propelling) to the Dark Angel in the 1948 Orpheus? The dramatic function of the 1948 Orpheus angel is surely based on that of Amor in the 1936 Gluck Orpheus and Eurydice.

21. Another possible precedent is Giselle, which both Fokine and Balanchine know well – chiefly Act Two. (Fokine supervised the 1910 Diaghilev production; Balanchine supervises the Paris Opéra one in 1947, coaching Tamara Toumanova in a way that Maria Tallchief - as she told Arlene Croce decades later - found transformed both Toumanova and Giselle, though in rehearsal rather than in performance. He is also believed to have assisted on Ballet Theater’s 1946 production, with designs by Eugene Berman.)

Albrecht traditionally enters the forest (the realm of the dead) along the same diagonal as the man in the Serenade Elegy. Russian and American productions of Giselle Act II often place her grave downstage right, close to where the heroine lies at the start of the Elegy. The idea of the man revisiting the tomb of his dead beloved, as in Giselle, and dancing again with her spirit before they are parted forever is one of the possible interpretations of the Elegy.

The ballet’s opening Sonatina movement places its women in a diagonal line that also recalls the wilis of Giselle, as does their rushing exit offstage to stage right. And Balanchine, in his subsequent changes to the ballet, adds three further elements that heighten the echoes of Giselle. See 74, 79, 81, 106, 112. (Both Adolphe Adam’s music for Albrecht’s entrance into the forest and the diagonal path he takes may well have been inspired by Orpheus’s entrance in Orphée et Eurydice, the 1774 French version of Gluck’s opera. That’s another story.)

It’s possible that “the girl who falls over” in the Sonatina (see 29, 87) is an echo of Giselle at the start of her Act One Mad Scene – or (in some earlier stagings of Serenade) Giselle at the moment of her death. It’s also possible that, when the Elegy’s heroine, left alone, rushes across the stage to embrace another woman who has just entered (downstage left), she recalls us of Giselle’s final run across the stage to recognize and embrace her mother Berthe (downstage right). That Serenade woman is now called “the mother” by New York City Ballet. (Gwyneth Muller, Serenade seminar August 27, 2015.)

22. Ruthanna Boris, in her account of the first rehearsal of Serenade (see 9). said Balanchine wanted every dancer onstage to be seen; the orange-grove formation was his solution. This may be the first of several ways in which Serenade reflected the democracy of America: theatrical visibility for each and every dancer. (See 23, 50.) Other touches of American democracy may involve Balanchine’s way of multiplying events that are usually for individuals: notably, the ensemble manège (late in the Sonatina, for fifteen women) of piqué turns, which hitherto in stage choreography have been a climactic solo effect for the ballerina solo (Siegel, Shapes of Change, pp. 72, 73-74) and the episode in the Elegy when eight men and four men go through a partnering exercise that becomes a quadruplication of the Elegy’s primary drama of one man caught between two women (see 40).

“Balanchine could almost be declaring his own independence from the undemocratic ranking systems of the old Russian companies, where this one is the Ballerina, another is the Cavalier, and others are the Corps or the Second Lead, and they never do anything more or less than their assignments… Piqué turns are a showy, applause-getting device usually performed by the ballerina at the end of a pas de deux. Yet Balanchine says all seventeen of these dancers can do the step. And the trick, done by so many, looks less exciting rather than more. Balanchine plays down its flashiness, incorporates it into the standard body of material that a corps de ballet can do in creating its ensemble designs.” (Siegel, The Shapes of Change, pp.72, 73-74.)

Yet Balanchine in several later ballets reverts in several later ballets to Russian-style hierarchy, and never again showed quite the same fluidity of ranking as he did in Serenade. A number of roles in the Sonatina, Waltz, and Elegy have soloist-type prominence for brief moments but belong to corps dancers who are never featured this way again. (The last of them - the woman who emerges from the wings downstage left at the end of the Elegy and is embraced by the heroine - is “the mother.” See 21.)

23. Is this emphasis on the individual within the ensemble a new reaction on Balanchine’s part to American democracy and to world politics? Certainly elements of world politics seem, obliquely, to have affected Serenade. See 9.

Robert Greskovic writes (email to Macaulay, September 2, 2015) that Barbara Weisberger has recalled that Balanchine said that, though he was aware this might seem a “Sieg, Heil” moment, his next direction was for a “bend/flex/relax of the wrist” - as if to flick that suggestion away.

Kirstein writes (New York City Ballet: Thirty Years, pp.39-40) that Balanchine began with a gesture. “When the curtain rises, the corps de ballet, in a strictly geometrical floor plan, are seen as a unison platoon standing at guard rest - or actually, in the first of the five academic positions which are successively assumed in the initial twenty measures of the music. Hands are curved to shield their eyes, as if facing some intolerable lunar light. At the first rehearsals all arms were stiffly raised, but since Eddie Warburg imagined that this resembled the Heil, Hitler arm-thrust salute, Balanchine altered it to a more curvilinear, tentative, and vague fanfare of indeterminate gesture.”

(Kirstein’s published writings on ballet, valuable on Serenade as on many other subjects, include a few factual errors. The one here about “the five academic positions which are successively assumed in the initial twenty measures of the music” is certainly one. This opening ritual includes first and fifth positions, pointe tendue in second, but not third or fourth. His words “guard rest… the first of the five academic positions” do not explain that, at curtain-up, the first position the dancers are in a first position, but not a turned-out one.)

Hitler and totalitarian politics are certainly in the New York air. Kirstein’s diary shows his occasional mixture of interest and alarm about communism, his rage about his friend the architect Philip Johnson’s interest in fascism, and his own composition of some Hitler poems:

“April 3rd. <after obtaining visas in Montreal for Balanchine and Dimitriew, describing the train journey back to New York> We were very gay: talked abt. Serenade & possibility of Uncle Tom’s Cabin & Eddie’s lack of seriousness. Dim. very formally thanked me for coming up to Montreal & doing all for them. He is a terribly tired man & his own passion is to retire to a desert isle & to have peace the rest of his days. They were both bitter abt. Communist Russia: Bal’s family in considerable distress at this moment & the superogation<sic> of personal liberty. G.P.O. to insupportable, and how it wd. surely come here if things weren’t done to stop it.

“May 16. Called on Phil Johnson at his big flat on E49.... I asked for an explanation of his ‘gray shirt’ fascist activities : demonstrated anger & intensity : he said the shirts had been abandoned. They were barely organized. They are not anti-semitic - & even hoped that nice Jews like Warburg & myself wd. join them. They were merely a group of young men interested in ‘direct action’ in politics , who believed in a totalitarian state and leadership instead of democracy. I explained that while I had no great fear of Phil Johnson or Alan Blackburn, nevertheless other such organizations were sprouting up all over, which <?> if corelated<?> cd. not afford to ignore the strong political weapon of anti-semiticism. He said he knew nothing he cd say wd. convince me but that his plans were not anti-semitic. I retorted : not yet.

“<July> 6. …Worked on my Hitler poems.”

“<July> 16. After some pondering wrote, as perhaps I shouldn’t have, to harry Dunham, sending him as an impersonal offering my ‘Lieder Für Hitler’ and a note saying I could (just) take no answer.” (Kirstein handwritten diaries, New York Public Library. Quoted by permission.)

24. Balanchine also makes a pointed use of all the soloists being part of the corps - perhaps something already uncharacteristic of him and something he generally avoided later.

The main hall at the School of American Ballet was large, and Serenade is felt to have reflected that. Leda Anchutina recalled “We ran and ran and ran.” (Nancy Reynolds, Repertory in Review, p. 36) This extensive and rapturous use of running has been seen as a quality evoking the style of Isadora Duncan.

Kirstein writes (New York City Ballet, Thirty Years, p.39):

“The prime quality of Serenade from the moment of its inception was cool frankness, a candor that seemed at once lyric and naively athletic; a straightforward yet passionate clarity and freshness suitable to the foundation of a non-European academy. Balanchine had not seen Isadora Duncan in her best days, but she had certainly affected Fokine, and might detect a strain of her free-flowing motion here.”

25. Edwin Denby later writes - in what publication or letter we do not know - something quoted by Bernard Taper (Balanchine, 1974 edition, p.169):

“He had to find a way for Americans to look grand and noble, yet not be embarrassed about it. The Russian way is for each dancer to feel what he is expressing. The Americans weren't ready to do that. By concentrating on form and the whole ensemble, Balanchine was able to bypass the uncertainties of the individual dancer. The thrill of ‘Serenade’ depends on the sweetness of bond between all the young dancers. The dancing and the behavior are as exact as in a strict ballet class. The bond is made by the music, by the hereditary classic steps, and by a collective look the dancers in action have unconsciously - their American young look. That local look had never before been used as a dramatic effect in classic ballet.”

But Balanchine's reaction to this Denby point was “Too fancy!... I was just trying to teach my students some little lessons and make a ballet that wouldn't show how badly they danced.” As Taper noted, this was “the kind of ingenuous, deadpan statement that he often makes and that he may or may not entirely mean.” (Taper, Balanchine, 1974 edition, p.169.)

26. The three leading roles we now know seem to have been shared among four or more women/girls. Casting for the 1934 premiere (see 36, 52-53) shows that the two lead female dancers of the Elegy did not dance in the earlier two movements. Kirstein (p.39) writes “At the start the chief solo role was shared among five girls; parts of it were later combined for a single soloist.” (See 77, 83, 93.)

27. In at least two ways, the Sonatina (like some other Balanchine ballets from the 1920s to perhaps the early 1940s) shows a connection to the style of Bronislava Nijinska.

Women, while holding arms en couronne, like a halo around the head, tilt the torso in different angles, as in Les Biches. (This in turn may well have evolved from Fokine’s choreography in Les Sylphides.)

An early multi-tier close-ranked pile-up for the female corps de ballet, upstage left, maintained as the “Russian” dancer begins her first solo, is remarkably like a four-tier pile-up for the men in the second scene of Les Noces. (This parallel is shown by Macaulay and Greskovic on March 24, 2016, “Rare Films and Illustrations of Balanchine’s Serenade”.)

28. A quite different resemblance has been noted (Croce, “Higher and Higher,” 1977: Afterimages pp. 268-269) – to the dance style of Jessie Matthews, an English dancer of stage and film (very popular in America as well, where she was called “the Dancing Divinity”). As shown on March 24, 2016, the especially Matthews look is in the way, at the end of the Waltz, the corps women perform swift backbends while pushing the air ahead of them with their arms (see 48); Matthews does this in “Dancing on the Ceiling” in her most beloved film, Evergreen (1934), itself an adaptation of the 1930 London stage show Ever Green.

In 1929 both Balanchine (uncredited) and Jessie Matthews had worked in London, separately, on the Charles Cochran revue Wake Up and Dream!. It was the first time Balanchine worked with Tilly Losch, who received, with Max Rivers, the credits for the choreography. According to Choreography by George Balanchine, this was Balanchine's initial choreography for British and American musical revues. Matthews danced non-Balanchine numbers.

In I Remember Balanchine, the veteran NYCB wardrobe supervisor Leslie Copeland says,

“Balanchine and I would reminisce about the past. He had worked in London with Jessie Matthews in the Charles B. Cochran revue, 'Wake Up and Dream!’ in 1929. That was before my time, but I had worked with her on BBC Television, so I knew her. Jessie couldn't really dance. She could do one thing and that was kick very high from the left. We would talk about Jessie. We used to laugh a lot about it.”

“Dancing on the Ceiling” certainly shows Matthews’s high kick, but it shows she could do more too. Croce in 1977 writes how Matthews “had forged a lightly idiosyncratic and highly appealing dance style out of ballet steps done in jazz rhythm” - something else Matthews had in common with Balanchine.

It's possible her “Dancing on the Ceiling” number contains a few other influences upon Serenade - the excitable series of piqué turns, the sudden penchées. When Balanchine lengthened the dresses in 1950 and 1952 (see 106, 112) he, perhaps accidentally, strongly heightened the resemblance of certain steps, especially the Waltz heroine’s manèges of piqué turns, to “Dancing on the Ceiling”.

29. There is no question about where we still see the “girl who was late for class” (see 7, 31); her entrance plainly occurs at the end of the Sonatina – interestingly, just as the music repeats the opening bars.

But “the girl who fell over” and began to cry has been an issue for some confusion. Kirstein establishes that this is the fall we see in the Sonatina:

“A girl tripped and fell over, close to the end of Serenade's first movement. This accident Balanchine kept as a climactic collapse by which a genuine minor mishap became a permanent framed controlling excitement, a contribution precipitating but by no means perpetuating chance.” (New York City Ballet, Thirty Years, p.39)

This is surely the moment, perhaps three-quarters way through the Sonatina, when, center stage, a girl suddenly turns and falls (or quickly lowers herself) to the floor. (Since the late 1950s, this has always been part of the “Russian” dancer’s role.)

Today, however, it’s often assumed that “the girl who fell over” moment is the more spectacular fall at the end of the Tema Russo or Russian dance. Since there was no Russian dance, this raises questions about how the 1934 Waltz (with its very different final music) ended and the Elegy began. (See 32 for a likely solution.)

The woman falling in the Sonatina is the most pronounced example of how Balanchine later, in his words (see 7), “elaborated on the small accidental bits I had included in class and made the whole more dramatic, more theatrical, synchronizing it to the music with additional movement.” After what has already been an extensive solo, this woman has a little exchange – a briefly dramatic incident, like dialogue - with another corps dancer, who emerges from the wings downstage left. After this exchange, that corps dancer is joined by fourteen others from various wings on both sides of the stage; these fifteen march on point with stiff arms towards the front-center area; and it is precisely there that the soloist now turns and then falls to the floor.

The formation the fifteen corps dances create is that of a three-tier semi-circle of five rows, like a Greek theater; as Bart Cook has remarked, they are “both theater and audience.” Arriving in this pattern, they execute staccato ports de bras – a striking example of the freeze-frame fragmentation of academic gesture that began with the ballet’s opening ritual – while she lies there and as she then rises.

When she does so, she embarks on the most complex jumps we have seen so far. (This resembles the Fred and Ginger “Pick yourself up, brush yourself off, start all over again.” Swing Time, 1936) Thus her “accident” coincides with one of the most formally choreographed passages in the whole ballet.

The fifteen corps women then proceed to the unison manège of piqué (or fouetté) turns, initiated by two of them. (See 22, 30.)

Colleen Neary recalls (email to Macaulay, April 28, 2015) that Balanchine told her in the 1970s or 1980s that, when the “Russian girl” falls over in the Sonatina, “It is as if she has fainted, after turning so fast, she reaches up and then faints, and then, after 1 x 8 on the floor, she slowly recovers and slowly crosses her foot over and gets up and rises on point in full strength.” Neary danced both the “Russian” and “Dark Angel” roles in the 1970s and served in the 1980s as ballet mistress to the Zürich Ballet, where Balanchine came to rehearse his works. She remarks “I am not sure if he was giving me the illusion, or if the girl in reality, years before, actually did faint! He demonstrated it to me, as a slow recovery and then rising up and then strongly doing the jumps that follow, facing back and the front and then relevé in arabesque.”

It also seems likely the ballet’s second fall, the one at the end of the Tema Russo, is planned by Balanchine as an echo of the first. The ballet abounds in echoes, suggesting flashbacks (see 15), second opportunities, and images of destiny.

Suki Schorer and Kyra Nichols Gray both spoke on August 27, 2015 (Serenade seminar) of Balanchine’s strictness about exact musical timing with the “Russian” soloist’s jumps after her recovery.

30. Annabelle Lyon (1916-2011), an advanced student of Michel Fokine, recalls a surprising point about Balanchine’s initial version of this choreography:

“When he originally did Serenade in 1934, the first movement concluded with the entire corps de ballet doing a sequence of fouettés. (Later he changed it to piqué turns.) I couldn’t do fouettés, so he had me run offstage just before that.” (I Remember Balanchine, p. 142)

This explains what has until now seemed Kirstein’s most puzzling statement on Serenade, in his 1939 Ballet Alphabet (often re-printed), under “Fouetté”:

“In Balanchine’s Serenade (1934), sixteen girls executed thirty-two fouettés without difficulty.”

Kirstein has described a fouetté turn accurately two paragraphs above. It’s probable he is wrong about the numbers sixteen and thirty-two here, but Lyon’s account corroborates his point, which hitherto has seemed unbelievable.

31. Balanchine actually sneaks another woman (seldom noticed) into the formation the moment before “the dancer who arrives late” appears, in the version seen since the 1940s or earlier. The “Greek theater” formation (see 29) and the unison piqué turns use fifteen women; the additional woman makes sixteen. So the latecomer, on arrival, completes the original formation of seventeen.’

It seems that Lyon (see 30) was the original “girl who arrives late” (see 7) – though Kirstein (see 7) recalls Anchutina as the original latecomer in rehearsal. Lyon recalls:

“Then, before the waltz began, I was the one who comes in late, looking for her place. Now when people try to put a meaning to that, it always tickles me. I didn’t have enough strength in technique, but I had a sense of all things I had learnt with Fokine. So Balanchine used a lot of lyric movement whenever he did a piece on me.” (I Remember Balanchine, p. 142.)

Lyon was indeed one of the five women who, with no man, were featured in the Waltz in 1935 (see 69). And Ruthanna Boris corroborates Lyon’s account:

“One morning he completed the first movement of the dance we had been learning by the end of our first rehearsal hour. He set a configuration that returned each of us to our original place and position in the opening picture – legs parallel, right arm upraised toward stage right, heads turned to the arm, eyes looking up at uplifted hands. One dancer was missing – Annabelle had missed class that morning, had been absent from the rehearsal…. Annabelle arrived for the second hour; he reviewed the ending, and, once we were all in place and beginning the last arm, head, eyes movements, he brought her in from stage left rear, wandering through the lines, looking for her place, finding it, assuming her arm position, looking up at her hand, then, he had us all drop our arms, turn away from her, and slowly begin to exit into the wings of stage right…” (Boris, “Serenade”: Reading Dance, edited by Robert Gottlieb, p. 1068.)

Boris goes on, however, to say that Lyon was then joined by William Dollar, with whom, Boris claims, Lyon then began the Waltz. Actually, no man dances in the Waltz until Balanchine revises it in 1936 (see 74). Boris’s memories here, therefore, are unreliable; they seem, however, to be generally good on other points. (See 9.)

Lyon also speaks of being the original “latecomer” in a 1979 oral history interview with Elizabeth Kendall (New York Public Library for the Performing Arts). She speaks entirely, though, as if Balanchine brought her back in for practical reasons, and makes no connection to his now famous use of the accidents of rehearsals. Therefore, despite Boris’s memory of Lyon’s late arrival in rehearsal, it seems at least possible that it was another dancer who arrived late in rehearsal (perhaps Anchutina, as Kirstein recalled – see 67);and that it occurred to Balanchine subsequently to turn that lateness into choreography for another dancer.

Over the years, striking differences emerge between the various journeys taken by this “latecomer” through the corps. Diana Adams, in Victor Jessen’s 1953 film, shows a route and manner unlike any seen today. When asked about the feeling with which they made this entrance, Kyra Nichols Gray (August 27, 2015) says “I was just trying to find my place without anybody noticing”; Allegra Kent (same day) says “I felt I was searching for something I knew I could never find.”

32. It’s possible or probable that the 1934-35 Serenade was not the continuous dance we see today (see 74) but three separate scenes, like those we see now in Tschaikovsky Suite no 3 (1970). The way the dancers are listed for each movement in 1934-35 programs (see 52, 69-71) supports this theory.

33. Though Kirstein is writing long after 1934 (New York City Ballet, Thirty Years), he may be right about that original version when he says:

“There were numerous novelties of pattern and plastic structure.... Asymmetrical units of shifting dancers seesawed in contrapuntal accord; a solo dancer, holding a half of the stage, was echoed by a unison group in unlikely opposition.”

34. As Nancy Goldner (Balanchine Variations) observes, the 1934-35 Waltz is very different from the one we now know, beginning with five women, and including no man. (See 52, 69-71.) The Waltz’s music suggests that the women cannot have moved in the way that five women do at the start of the 1940 Russian dance. Do they echo the chain of five women who make a brief part of the Sonatina?

Some 1935 photographs show five women together. Their horizontal grouping, somewhat resembling the one we now see at the start of the Russian dance (Tema Russo), probably shows us the start of the Waltz as it was then.

35. Does the end of the Waltz, however, already feature the phenomenal geometries and counter-rhythms (corps of sixteen women with “Russian” soloist at the center) we see now? Very possibly, yes. The program for the June 10 premiere (see 52) shows the Waltz uses the female ensemble of nineteen women; and Kirstein’s point about “numerous novelties of pattern and plastic structure” may include this. Certainly the 1940 film shows a glimpse of this formation.

In this exceptional passage, the corps begins in two diagonal lines; the soloist is upstage where the lines meet. The two diagonals cross the stage horizontally, passing through each other while each maintains the same diagonal line; but the soloist (the “Russian” dancer in today’s casting) passes down the centerline toward the audience. On August 28, 2016, at the Serenade seminar, Victoria Simon (also shown on screen on March 24, 2016, “Rare Films and Illustrations of Balanchine’s Serenade”) analyzes the counts involved here: one line is a count ahead of the other, and the soloist “Russian” dancer advances to different counts. The two lines of the corps are doing a version of what Arlene Croce calls “Jessie Matthews backbends”, pushing their arms forward into the air while suddenly arching back. (See 28.)

Ruthanna Boris, however, writes that, in a rehearsal for the end of the Waltz:

“Heidi Vossler” <sic> “fell down during the exit, far downstage right. She scrambled to get up, but Mr. Balanchine said ‘No, you stay, others go.’”

But casting shows that Vosseler did not dance in the June 10 premiere of the Waltz. (See 34.) This therefore seems another of Boris’s wise-after-the-event memories. (See 9, 31).

36. Kirstein’s March 26 diary entry (see 6), about the “wonderful pas de trois of Heidi Vosseler, Charles Laskey and Catherine Maloney”, is surely a reference to the choreography for the Elegy, which featured Vosseler, Laskey and (the more usual spelling) Kathryn Mullowney.

Heidi Vosseler (1918-1992) is the original “heroine” of the Elegy. (See 44, 53.) The June 10 program (see 42) strongly suggests that she only dances in that movement.

This confirms the idea that Balanchine originally conceived the three movements as separate scenes without any through continuity. By August 1935 (see 71), she is also dancing a corps role in the Sonatina, but remains absent from the Waltz.

If Balanchine is right in remembering that, when one man attends rehearsals, he puts him into the choreography, that man seems to have been Laskey (1908-1998). Other men had already taken classes at the School of American Ballet, we know. Is Laskey just lucky in his timing? Laskey dances this role in Serenade until at least August 1935. He later danced for Balanchine on Broadway and in Hollywood. Boris describes him as “tall, strong, and handsome”; although other parts of her account are unreliable, here she confirms that Vosseler, Laskey and Kathryn Mullowney (her spelling) are the opening trio of the final Elegy.

Catherine Maloney’s names are spelled at least two other ways in 1934-1935: Katheryn and Kathryn, Mallowney, Mullowny, and Mullowney (see 52-53, 69). She must have danced the role now known as the “Dark Angel” and did so (though not in February 1935) till at least August 1935. In a 1976 oral history interview (New York Public Library for the Performing Arts), she recalls dancing in the Elegy of the original Serenade without specifying her role. She says, however, that she had “a high arabesque”: often a crucial element for a Dark Angel.

37. For the opening of the Elegy, Boris recalls that Balanchine:

“placed Charles <Lasky, her spelling> in front, bent forward from the waist with Kathryn draped over his back and had them enter from upstage left in that position, moving on a diagonal toward Heidi. He fussed with their positions a bit, then had Kathryn wrap her downstage arm around Charles’s chest and cover his eyes with her upstage hand. It made an interesting, dramatic picture as they slowly advanced toward Heidi, lying stretched out on the floor; that was the beginning of the last movement, the Elegy. After rehearsal, I said ‘Mr. Balanchine, how did you think of that position for Kathryn and Charles Laskey? It’s very interesting and dramatic.’ He smiled and whispered, as if it was a secret, ‘You know, Lasky, he is very near-sight. I thought he does not see, so, maybe more comfortable if eyes have cover and Kathryn looks where to go.’” (Boris, “Serenade,” in Reading Dance, edited by Robert Gottlieb, p.1069.)

Colleen Neary recalls “When I did the "dark angel girl", he always said "walk with man and you are his eyes, because man cannot see" (email, July 14, 2016)

38. The Elegy seems always to have had the same overall structure: the heroine on the floor; the man who arrives with the Dark Angel; her promenade arabesque turned by her thigh: their trio; the other women who rush by and the one dancer who joins them for a quartet; the episode where four men partner eight women: the return to the trio: the Canova/Eros arms moment: the departure of the man and Dark Angel, leaving the “heroine” alone on the floor: the arrival of other women: the suggestion of her awakening; her rush to the anonymous “mother” figure, the three men who help to carry her away.

Although quite a few aspects of this Elegy seem to have come from Fokine's Eros (see 13-15. 18), these do not include the arabesque promenade, the episode for four men and eight women, or the final lift and departure. (Robert Greskovic observed - August 28, 2015 - that Balanchine had used the arabesque promenade, by the supporting knee, in La Pastorale for Felia Doubrovska.)

The final departure and other parts may have connected to Balanchine’s own early Marche Funèbre. Robert Greskovic observes that the Marche, according to Kendall’s Balanchine and the Lost Muse, was costumed in knee-length tunics of black and gray, designed by Boris Erbshtein, somewhat related to those to those proposed by William B. Okie in 1934 as well as those by, or attributed to, Lurçat in various forms in the years 1935-47. Greskovic in 2016 observes that the Balanchine Catalog on line attributes the Marche Funèbre scenery to Erbshtein but its costumes to Vladimir Dimitriev. Greskovic identifies this as Vladimir Vladimirovich Dimitriev, not to be confused with Vladimir Pavlovich Dimitriev or (Kirstein’s spelling) Dimitriew (see 1, 6, 20, 45, 47), Balanchine’s fellow Russian émigré and right-hand colleague at the School of American Ballet. But see also 39-44.

39. Balanchine interrupts and relaxes the Elegy’s chief drama, which concerns one man and two women, by introducing a stream of other women. One of these women (the role performed today by the “Russian” dancer) soon returns and becomes part of a sustained quartet.

On both her entries, she arrives in the man’s arms with highly dramatic jumps (each different), which Balanchine was often prepared over the decades to rehearse many times to get them to his satisfaction. (See Pat McBride Lousada, 102.) Patricia Wilde’s skill (in the 1950s) in the initial jump – a grand fouetté sauté upward to arrive backward on the man’s chest and in his arms – is one of the moments David Vaughan can never forget. Kyra Nichols Gray, at the Serenade seminar on August 27, 2015, says that, when she first did the role with City Ballet in the late 1970s, Balanchine must have made her do this jump “fifty times.”

40. Balanchine always says that one of the “accidents” of the 1934 rehearsals was that one day four men arrived, after a sole man had arrived on an earlier day. The sole man arrived in time to be the hero of the Elegy; the four men (known as “the Blueberries” by today’s Serenade dancers) arrive later in the same section.

Although their scene is a diversion from the main dramatic situation (one man, two women) and proceeds like a formal exercise in partnering, it also (see 22) formally quadruples it (four men, eight women, at one point making trios whose arms recall Canova’s Cupid and Psyche) while providing one of the few examples of same-sex partnering in Balanchine.) Immediately after the departure of these twelve dancers, the action returns to the central drama for three people, with imagery closest to Canova’s configuration. (See 14.)

Strange though this may seem today, it's possible - even likely - that the sole man was also one of the four. (See 53.) There seem to have been only four men in the June 10 premiere. This, however, was one of the first things Balanchine certainly changed. Five men are listed at the January 1935 performance.

41. The Elegy’s hero is reclaimed by the “Dark Angel,” who beats her “wings” three times in a way Balanchine took care to rehearse over the years. (See 102.) Without a change of rhythm she folds her arms/wings over his chest and eyes, and steers him offstage.

Left alone, the heroine (in 1934, Heidi Vosseler) rises again from the floor. She is joined by a small community of seven women from downstage left. She embraces one of these – the role today known as “the mother” by City Ballet dancers (see 21). She, the heroine, kneels at the “mother’s” feet, and, opening her arms wide, arches her torso backwards in a way often considered tragic; at the same time, her backbend may be related to the final bend of the neck and head of the ballet’s opening ritual. (See 4.)

Three men then enter. Her torso returns to the vertical; she sees them; she stands. The men then lift her, like an effigy, and slowly carry her on a diagonal to the upstage right corner, while the seven women ceremoniously attend them.

This slow-traveling cortège diagonal effect resembles two in the ballets of Léonide Massine. At the end of the pas de deux in La Boutique Fantasque (1919), the female Can-Can dancer is carried slowly upstage along the opposite diagonal; at the end of the first movement of Choreartium(1933), the lead male dancer is carried on a downstage diagonal. Frederick Ashton has imitated the Boutique cortège closely in Les Rendezvous (1933) and does something similar with a group in Les Patineurs (1937).

42. But the drama of the Balanchine cortège nonetheless seems different, not least because the heroine is standing erect and because she opens her arms and face to address the heavens: the ballet’s final echo of its own opening ritual. (See 4, 14, 85.) The suggestion that she is moving off into another life - or another stage of life - makes the ending of Serenade resemble a number of works in which the protagonist departs into the realm of the sublime, as in Marche Funèbre (1923), the original Apollo (1928, with the ascent-to-Parnassus ending still seen in some stagings today), Le Baiser de la fée (1937), Night Shadow (1946).