Margaret Jenkins on Merce Cunningham (and on Carolyn Brown, John Cage, Brigitte Lefèvre, Sara Rudner, Gus Solomons Jr, Twyla Tharp)

The choreographer Margaret Jenkins has been a leading figure of Bay Area dance (California) since 1970. As she relates here, she studied with Merce Cunningham from 1963 to 1970, became a trusted friend of his, and staged his Summerspace (1958) to two European companies and the Boston Ballet as well as to the Cunningham company itself at one time.

Jenkins knew of my Cunningham research, but we had not met when she agreed to speak to me by telephone on two occasions in July 2019. We immediately connected as friends, as in subsequent communications.

I: 2019.vii.19

AM. So what was your first experience of Merce Cunningham’s work?

MJ. At UCLA in 1963, in a three-week workshop I was part of, and in their performances there at Royce Hall.

Previously, I had been at Juilliard for a year, starting in 1960. It wasn’t a good match, but I wouldn’t really come to understand the complexities of why it wasn’t a good fit until years later. I was a teenager from San Francisco, where I had excelled as a young modern dancer and was considered quite talented, with potential - only to find at Juilliard that I was not at all exceptional and that, in relationship to those for instance from the High School of the Performing Arts, I had a long way to go to be competitive with that level of skill. That was hard, a severe reality check.

The techniques and composition I learned there were quite traditional in approach and, one might say, of necessity for a young dancer. The music education was revelatory and has stayed with me to this day. I received extraordinary exposure to the most distinguished dance icons – composition from Louis Horst and Lucas Hoving, technique from Martha Graham, José Limón (techniques I had studied in San Francisco), and Anthony Tudor - but I was craving - without understanding what - something other. After one year, of an unidentified discomfort and longing, I left. I wish I had been more ready and open to all of it! But then, the timing of leaving and going to UCLA were life-changing.

The next year, I went to UCLA. There were people teaching there who had come fresh from the early experiments at Judson Church, notably those led by the now famous composition class of Robert Dunn[1]. Everything and everyone was on fire and all was being questioned – form, content, technique, performance!!!

I had been raised in modern dance in San Francisco, starting at the age of four; the school, Peters Wright School of Dance, exposed us directly to as many traveling artists as they could: to Charles Weidman, with whom I studied, and regularly to the techniques of Martha Graham and José Limón. At age 11, I went to Salt Lake City to study with May O’Donnell and Harriet Ann Gray which provided another view of what was possible.

Merce was not part of that lineage made visible in any of the above places of study. Juilliard did not “recognize” Merce. It was not a name or philosophy I would encounter until years later at UCLA.

I had some wonderful teachers at UCLA. My first year and a half brought me into contact with Judson-connected people who had studied with Robert Dunn in New York in the famous and infamous composition class that exploded the ideas of “What is composition?” and “What is form?” and “What is an idea?” and “What is or is not the relationship of music to dance?”. At UCLA, I was nineteen/twenty years old.

At Juilliard, I’d been studying traditional compositional forms: ABA – Sonata form. Dance composition, it was suggested, was to follow musical form. Dance was the articulation of music. One first found a music that inspired, then one made a dance.

Looking back, at my time at Juilliard, I wish I had been more grounded, secure, more ready to just study what was offered – as a scholar might, but I was young and the competition was paramount and I was not ready to handle it all. I was a rebellious teenager without much focus, but I knew “this just doesn’t feel right.” I was just not able to identify what I needed until UCLA, when alternative ways of thinking about composition and form were presented.

AM. Were you hungry for the new ideas that Cunningham and his colleagues brought you about form and composition? Or did you find them slightly shocking too?

MJ. It was shocking to me. There was something disquieting about it – disorganizing but also exciting with the promise of a new way of imagining art.

And I also knew, at Juilliard, I hadn’t found the right technique. Or I knew there must be something out there, a well-rounded training that was waiting…

A year plus after I arrived at UCLA, 1963, Merce came; I knew very little of about him. I’d never heard of him at Juilliard. He was a kind of whisper at Connecticut College where I went in the summer of 1960.

At UCLA, he arrived with his company, for a 3-week residency, with Robert Rauschenberg[2], Jasper Johns[3], John Cage, Carolyn Brown[4], Viola Farber[5], Steve Paxton[6], Shareen Blair[7] – “the squad” if it’s all right to use a term Trump has recently made horrid. (Sandra Neels[8] was there as an apprentice as well.)

It really did blow and open my mind. It was electric. I hadn’t read extensively about him. I hadn’t seen his work. I didn’t know anyone who had.

This extraordinary group of dancers and humans that landed on campus with Merce would change the course of how many of us thought and questioned and trained. I didn’t know at first how exceptional it was. It just was!

It was the beginning of a different education for me, a launch into adulthood, aesthetically, emotionally, and physically – a demand that I rely on my own intelligence, an insistence that I bring my full person into play.

Merce was just this kind, rather elusive, man who, by what he did, not by what he said, made discipline and rigor and the love of dancing visible. Cage, Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg – they were only on the edges of famous then, which, in retrospect, made them more accessible perhaps. They were just “guys” who liked to hang out with one another, make art, challenge what was considered the status quo, but primarily make work that reflected who they were, how they experienced the world around them.

For three weeks, we engrossed ourselves in the aesthetic - from classes to rehearsals to talks in between; we took class; we followed them everywhere they went. We were nineteen year old, after all.

(They were staying in Malibu and we’d drive to where they were housed and peek in through the wire fences and watch them at their pool.) We were becoming groupies!

We were being given the privilege of being introduced to the pedagogy in all its subtleties and complexities. For me, my mind, body, and heart had all found their place – an arena which redefined for me how to move forward. The nature of how I thought about or had experienced the world – what I observed in my brief time on the earth - had not heretofore found a “field” in which to land or invade, so to speak, a new way to consider training the body and the brain from which to make dancers and continue one’s investigations. Now I did.

Merce taught composition class. One thing: when I was struggling to put together a series of thirty-second segments he had asked us to make (I was agonizing, wanting to impress him, of course), he said: “anything can follow anything.” That quickly freed me in the way that chance freed him from the strictures of his own mind perhaps.

It’s always fascinating when “lessons” land. They don’t necessarily land when they are taught - like in 1963. Fifty years later, I can find myself saying: “Maybe that’s what Merce meant!”

Chance methods opened up ideas about sequence and form, and pushed the mind past what it could do when it tried to stay in control.

As Merce started to get to know me personally in those years, we talked more. I began to realize that I had been trying to push aside “all that chaos” that had defined my early life (being a version of a Red-Diaper baby and all the traumas that that encompassed!). Nobody else to date had encouraged me to embrace who I was, where I had come from in the way Merce did. Curiously, he was very astute, both psychologically and philosophically.

Merce and John: they embraced a kind of optimism, a humanity that revealed itself in how they interacted with us and with one another. Rigor was a mantra - the silence and repetition you had to embrace fully, if you were to truly understand the craft.

AM. What was novel about the Cunningham technique to you?

MJ. In the Graham technique which had been part of my early training, you began by sitting on the floor for forty-five minutes, and a lot of what one did DID give you strength of a certain kind. But with the Merce technique, it was about being on one’s feet, ready for action in any direction at any time. Training was about moving and the strength and agility to change one’s mind. Class began standing; one never sat down except if from a fall (choreographed) and then one had to quickly recover.

The Cunningham technique demands – this was a big challenge for me – that you are really on your legs all the time.

The Graham technique relies on ‘contraction and release’ at the pelvis with an implied drama from one’s center.

The Cunningham technique strips you of drama/character: you can’t rely on a narrative to define one’s moves. There are no frills. You either can stand on your leg(s) or you can’t. It makes the dancer naked, no story to protect or hide the lack of technique. That may be why some ballet dancers find it the most congenial modern technique: it’s so familiar.

Above all, it’s a phenomenal training for the mind as well. Once, when I was in New York, Merce had been away on tour; I knew he was coming back, and said to another dancer as we climbed the steps to take his class: “Why am I so anxious? I’m not anxious about seeing Merce; I’m nervous literally about class.” As we discussed this, we realized that we were most likely anxious about whether our minds were up to the task.

In Cunningham, no two classes are the same or were the same, at least after the initial warming-up exercises. Monday’s and Tuesday’s classes are completely different: nothing’s repeated. Other techniques almost always give you the same phrase to repeat a number of days. Not only was this rather extraordinary but it was challenging for everyone - Merce too, I suspect.

AM. When did you first sample Merce’s teaching in New York?

MJ. When Merce & Company departed after that UCLA residency in 1963, I was bereft and was anticipatorily deprived. So I boarded a Greyhound for New York. I called my parents from New York. They were less than happy. They made a deal with me: I would go back to UCLA for one more year: “If after that you still want to return to NY, we will support you in whatever ways we are able.”

That was fair. Merce hadn’t invited me to New York. I was just being a groupie. So I went back to UCLA. The next year there, which continued to be wonderful, I met Gus Solomons[9], Jr. He invited me to New York, to work with him, as his dance partner. I also knew I could continue my studies with Merce. That was 1964; I went to New York! Gus and I worked together, as dance partners, up to 1967 and performed in New York and Boston, a duet: simply this fondness, with David Vaughan reading Gertrude Stein.

I studied with Merce at the 14th Street studio. There were about ten of us who weren’t actually in the company: Twyla Tharp[10], Gus Solomons, Elizabeth Keen, Valda Setterfield[11] (who had danced with Merce but wasn’t yet a full-time company member then). We were just taking class every day with Merce.

I was dancing with Gus – and soon with Twyla Tharp. In class one day she said: “What are you doing tomorrow? Come to rehearsal!”

From that point on, I was working with Twyla and her husband Bob Huot at the time[12] and a couple other dancers. We were making a work for Hunter College: Tank Dive. At one point, as we rehearsed, she said: “I need another dancer. Do you know any?” I said “Sara Rudner[13]”, whom I’d seen with Paul Sanasardo’s Company. I took Twyla to watch Sara dance. Halfway through, she leaned over said: “OK, she’ll do!”

Twyla, Sara, and I worked together for five years which included performances in NY and Europe.

Twyla, Gus, and all took class (not Sara) with Merce. When Merce went out of town - we were all terrible snobs - we couldn’t possibly study with anyone else; so each week, it was someone else’s turn to teach the class. I had some experience teaching, so eventually it was my turn.

One day (1965), as we were “unwinding” from the first exercise and I could see Merce was standing at the back of the room about to take class. I whispered to Gus, “Merce is in the back!” Gus whispered, “I see!” I continued, “I can’t teach!” Gus said, “I don’t have class prepared. Get through it, girl!” And so I did.

Merce came every day that week to take my class. At the end of the week, Merce said “That was a really beautiful set of classes that you just taught. Here’s what I think. I should open a studio ongoing so when I am out of town classes keep going; I should engage June Finch and you to teach whenever I’m out of town. Interested?”

So that was the beginning of his school!

AM. What did you think of the Cunningham dancers of that era?

MJ. It was a group of very disparate and extraordinary characters. Steve Paxton; Remy Charlip[14], still around for a bit; Carolyn Brown; Viola Farber; Marilyn Wood[15]; Albert Reid[16]; Sandra Neels, Shareen Blair… They were all very different from one another, in their physical capacities and the drama that they held, the stories that they held in their bodies. I found those differences compelling and riveting. The complexity of them individually emanated from the stage and gave the work its own unique drama or narrative if you will. I was fascinated by how they in their differences defined the work. Of course it was Merce’s vocabulary and decisions, chance or not, that defined the work, but they inhabited the stage with their own “stories.”

Viola Farber had an extraordinary way with her body, as opposite as could be from Carolyn Brown. I loved what that said about Merce, that he saw the beauty in their difference and what they brought to the work and to him - his relationship with women, his own volatility. I experienced him as a very nuanced and perceptive person, and his relationships with men and women in all their complexities, were revealed in the work. I think he loved Viola in a special way. He admired Carolyn and loved her differently. And Barbara Dilley was sensuality personified.

When he was actively performing, so much seemed possible. What he could do onstage, how he lived between the steps, inside the rhythm. It’s been wonderful to look at the clips released this year by the Cunningham Trust. I was very moved by the characters that emerged in all the dancing in all the work.

I think of Summerspace, Place, RainForest, Sounddance, as embodying a kind of politics, a hidden narrative perhaps. They either were a direct response TO what was going on or as a way to deny what was going on. He was not not in the world; he darted around its edges, but was fairly placed at its center too. I felt that they did reflect the times he lived in. I appreciated he never wanted to talk of politics directly; he didn’t have to; he made dances instead.

AM. Did you observe a change in the company after its 1964 world tour?

MJ. Yes, I saw a change in the company. After forty-five plus years of running a company of my own, I sympathize: I understand how the energies of different people, each trying to navigate life and the hardships of keeping on as dancers can impact the chemistry of the group - the ruptures that can happen between people. There’s the fantasy that a company is a form of family and it is, but as with families, the dynamics are always shifting and it isn’t magic when it works; people have made an effort, a collective effort to understand one another and be sensitive the ongoing dynamics. You have to set up systems whether spoken or understood where everyone feels protected to keep the community of makers moving forward feeling safe and creative.

You have to have someone asking the right questions and making the space one of comfort, albeit full of risks - to find solutions: that was not Merce’s gift. He was not a facilitator or mediator. He just made dances.

John had the capacity to bond people together – at least through humor and sensitivity to the collective. That 1964 world tour was a very long one: everyone was left without the concomitant support systems you have when you leave rehearsal and go home to others and something other to balance out the day.

AM. Were you hoping to be taken into the Cunningham company?

MJ. Yes, I did harbor serious ambitions to be a dancer with the Cunningham company – until it became clear that I wouldn’t be asked. And even then there was a longing.

Until 1967, when I staged Summerspace for the Cullberg Ballet[17] in Stockholm, I had hoped for that relationship. Each time Merce took a new woman into the company, I’d be aware it was “not my turn yet”, (a fantasy, I would discover); or that was the formation I concocted, but I’d hoped that moment might still be mine. I kept trying to figure out why not. But now, having been a choreographer/director for over 49 years and chosen over 135 dancers, I know it’s mercurial at best why one makes those decisions – why someone catches one’s fancy. And I don’t think I can really know exactly why Merce did not see me thus.

I know I suffered when he chose Yseult Riopelle[18], the French dancer, in 1966. But I temporarily consoled myself with the fantasy that it was because her father Jean-Paul Riopelle had given money and a painting to help the company. Who knows? Merce was not the kind of person you could approach and ask why or I chose not to.

And a wise friend said to me after Stockholm (after I had taught Summerspace to Cullberg Ballet): “He’s not going to take you into the company.” I looked at her with some degree of naiveté. So she went on: “You’re actually too valuable to him in this capacity. And you’re really lucky to have this kind relationship with him. He needs you to stage his work and you get to be his friend in a unique way.”

AM. How did the friendship develop?.

MJ. Once, after class, Merce said “You’re looking awfully tired.” I told him of all the jobs (modeling, waitressing, etc.) I was doing. So he asked if I’d like to take on a very lucrative job he’d been offered, teaching one day a week in Rochester. I could fly up one day a week to do it; I could quit all my other jobs. That was an amazing gift and really changed how I trained. One day a week at Rochester supported me. My rent was $38.00 a month.

Later, when I moved back to San Francisco – not uncomplicated in terms of maintaining an ongoing relationship to him - he called me every Sunday for four years. It was at 11am; he’d call: “Hi - I’m in the studio. What are you doing? What have you been working on?”

I’d ask him the same. I was still doing things for him – staging Summerspace for Boston Ballet, for example or working on the Theatre du Silence coming to San Francisco to continue learning Summerspace. He’d say “My plants are growing so big” or “John’s driving me crazy.” It wasn’t so much the subject as the hearing of his voice, his sweetness and care.

AM. You mentioned staging Summerspace. How did that come about?

MJ: My connection with Summerspace came about in New York when Merce taught a series of workshops; I took the one on Summerspace.

I’d learned Labanotation (Laban), which I was good at, at Juilliard. I loved symbols. There was no such thing as video in those days, so the Laban system was a useful way to record dance, but hardly adequate for Merce’s work since it did not have a relationship to musical structure.

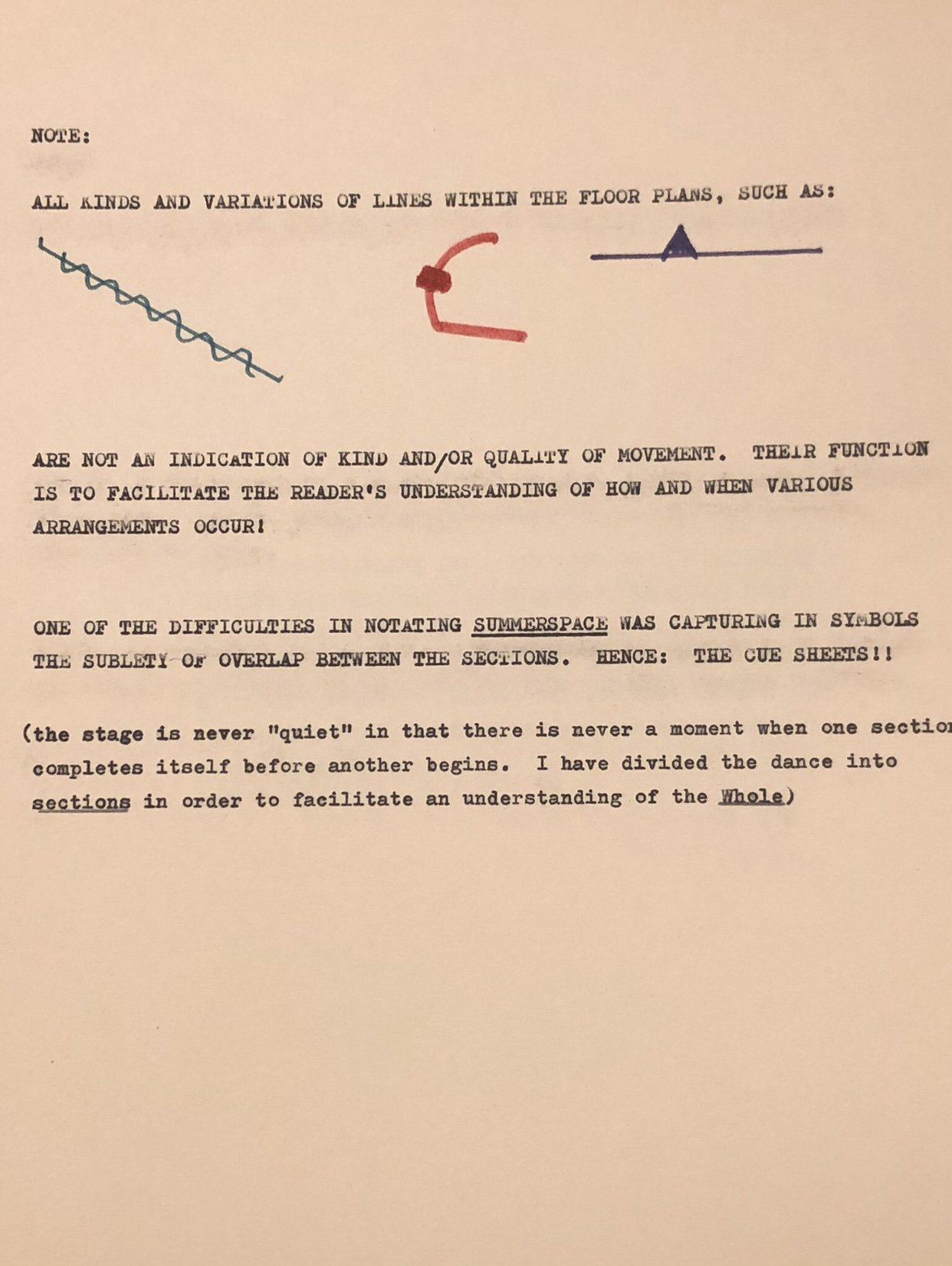

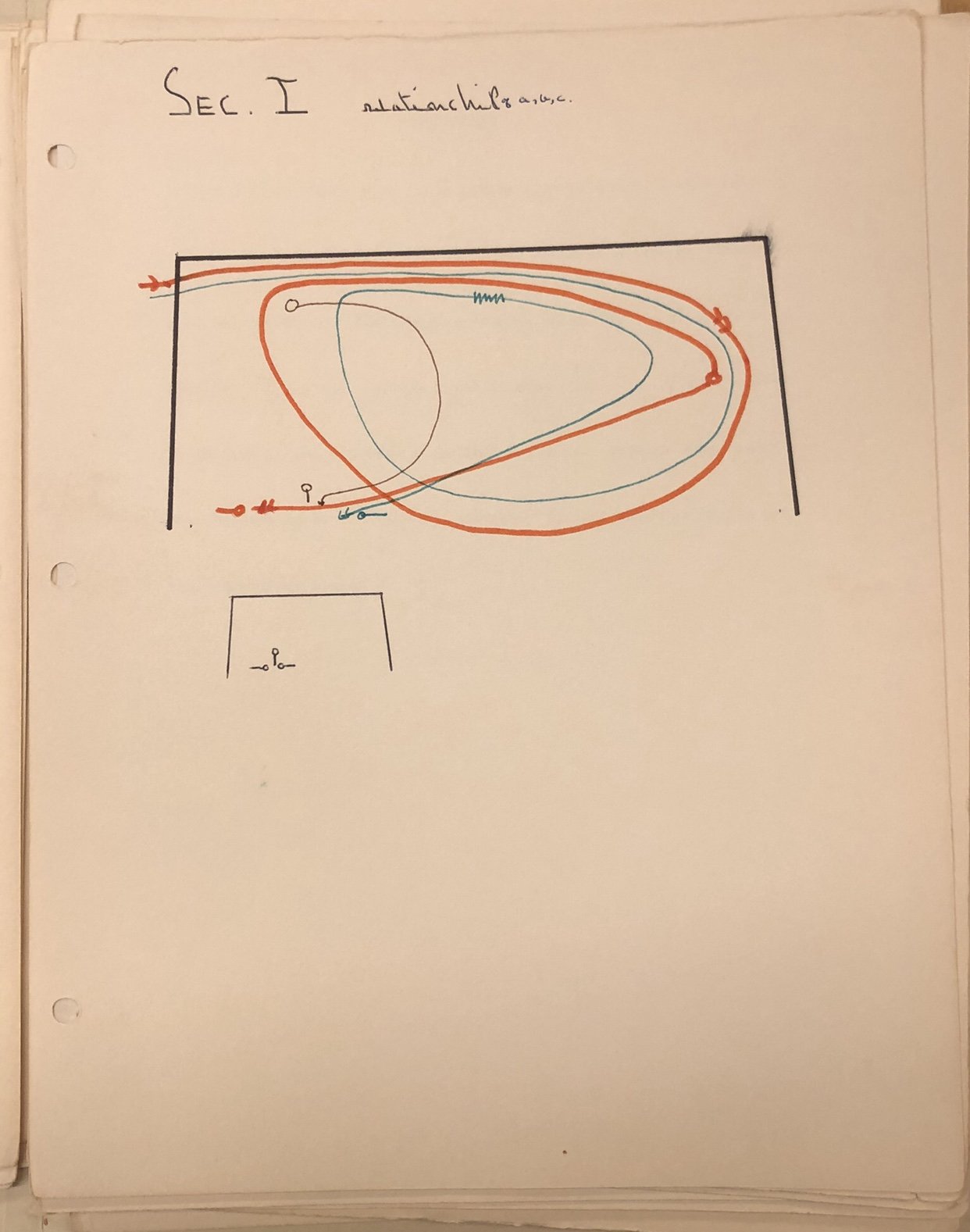

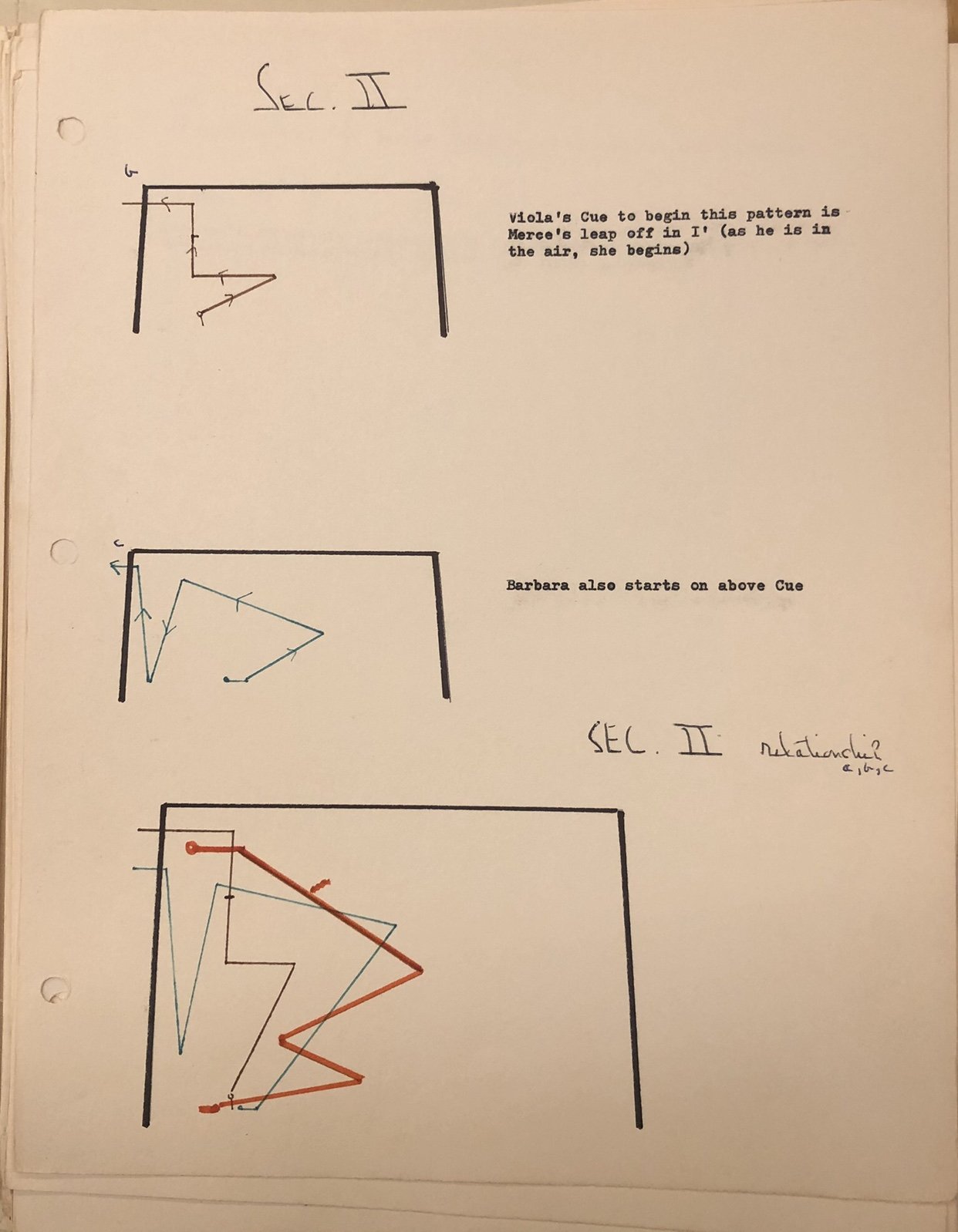

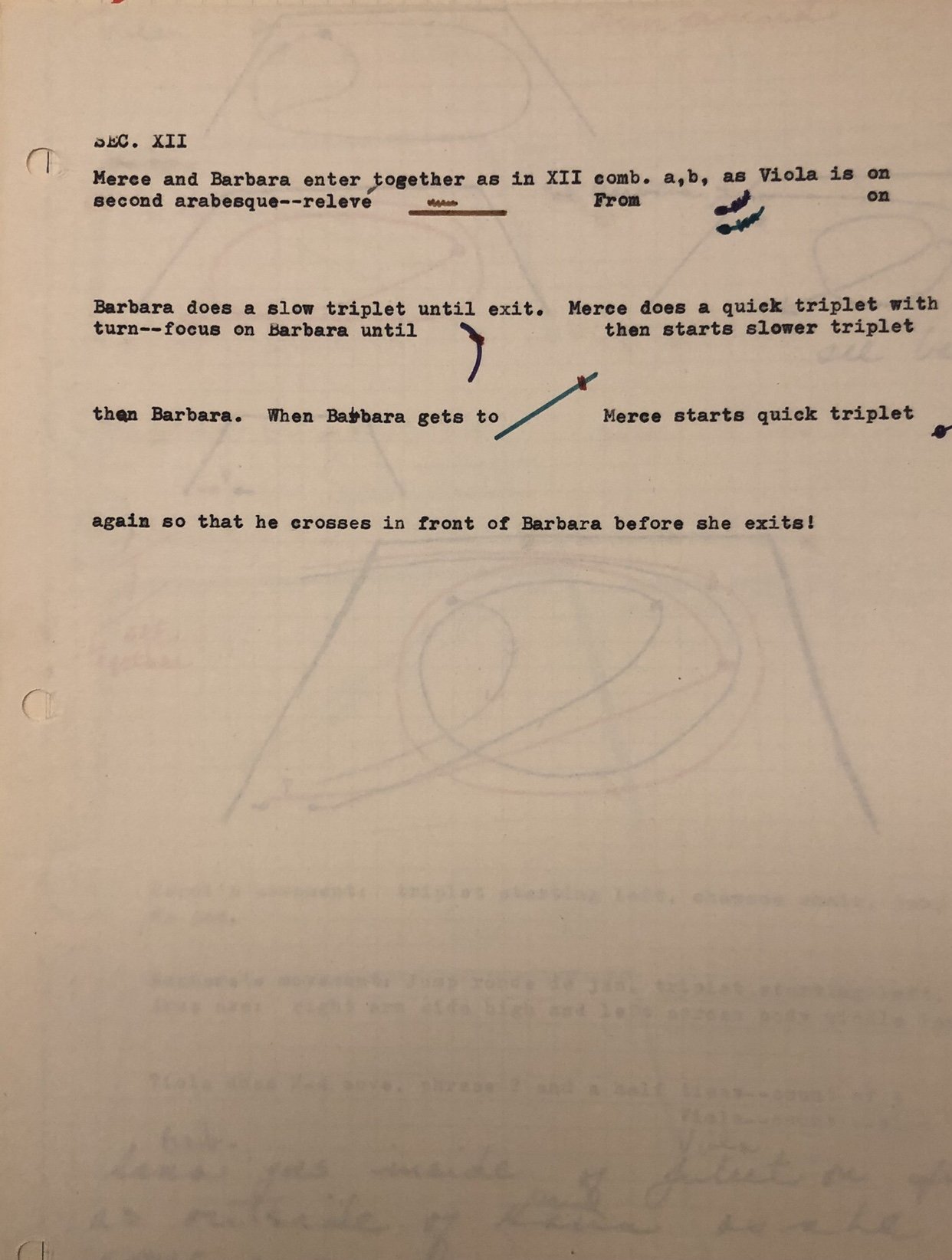

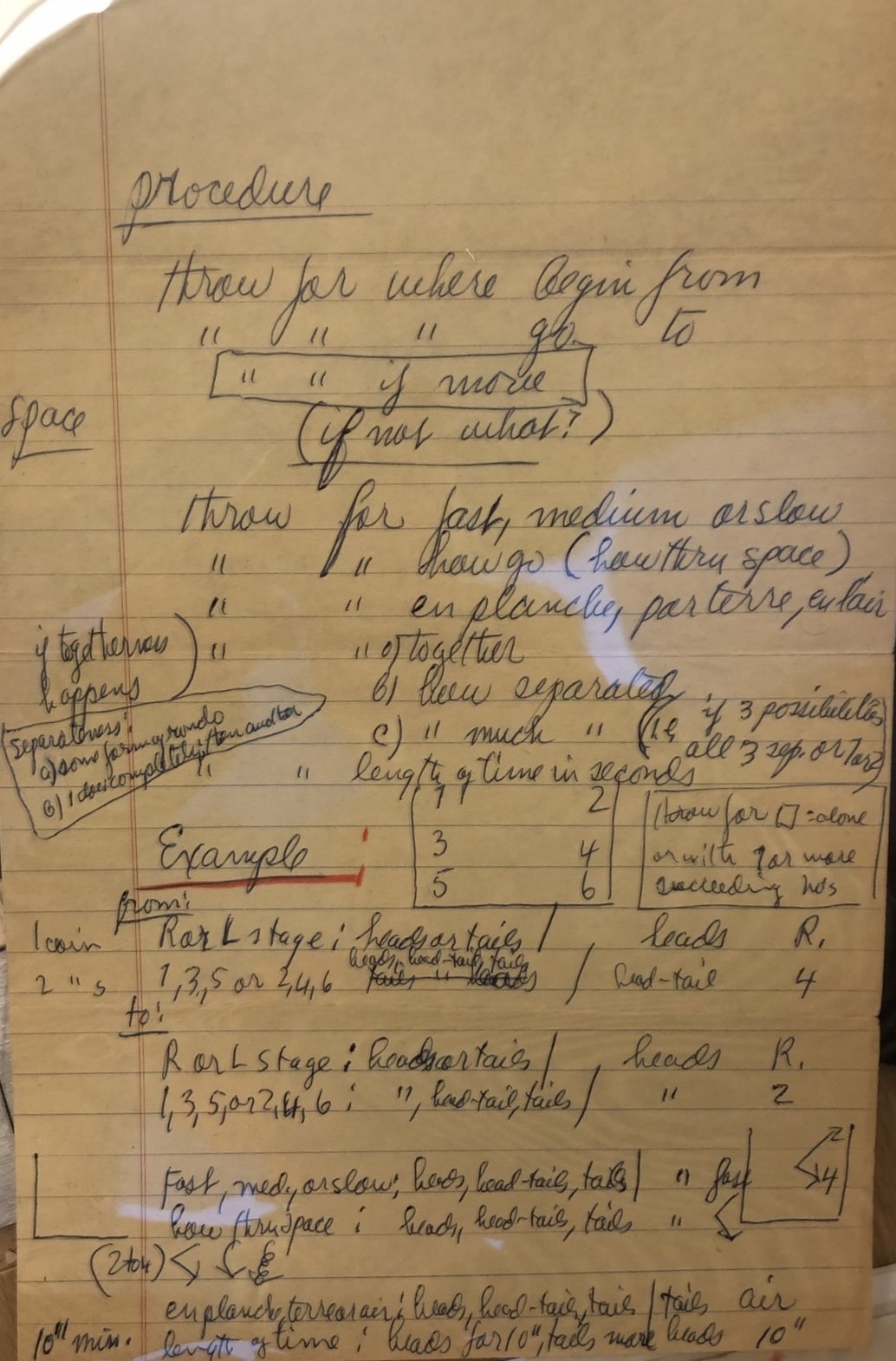

Laban could catch gesture to some degree, but - given it, Laban, was designed for a musical grid and of course there is no musical grid for Merce’s work - that system was not a thorough option. So I devised my own method of notation, using Laban and my own symbols and graphs and ways to indicate space shifts. The dancers in Summerspace are all so isolated from one another, but spatially dependent: they don’t ever touch, so I could notate each dancer separately.

Merce saw me at work on it and asked what I was doing and said “It looks colorful!... Why don’t you show it to me when you’re done?”

(Sara Rudner and I lived across from each other on Broome Street. We would give each other class across the alley! I remember I told her one day “I’m too busy for our class; I’m working on this tomb for Merce!”)

I made my notation into a book –– a giant book.[19] I presented it at the end of the workshop with excitement and trepidation. “You can keep it,” I told him at the end of class.

Soon after, I went on tour with Twyla Tharp and Sara Rudner to Paris, and Germany! Often there were less people in the audience than there were onstage so Twyla would put the audience on stage so we’d have a bigger area to dance where the audience would have been seated– especially in Paris; and we were often sleeping in somebody’s attic.

Merce called me when I was in Paris very unexpectedly of course, and said, “Would you like to try out your notation?”

He’d been asked to stage Summerspace on the Cullberg Ballet. He told them “I’m really too busy – but maybe Margy[20] would like to try out her notation.” I was beyond thrilled and scared and touched.

One week later, after the Tharp tour, I was on the plane to Sweden. (I left Twyla to pursue this connection to Merce; Twyla didn’t speak to me for fifteen years! In due course, she recanted and our friendship resumed. When she needs to remember one of the early works!!!!, she’ll reach out. But one can feel her tenderness. Time heals.)

AM. Can you talk about Summerspace?

MJ. I was nervous about staging Summerspace – beyond nervous. Carolyn <Brown> had been the one who’d staged it on New York City Ballet the year before.[21] So this was the second time it had been staged on another company. It’s a very “sparse” work, each dancer has his/her own unique spatial pattern, which is their own quiet narrative, intersecting in pashing with another dancer. So it combines complexity of the technique with simplicity of space. Every horizontal path, every diagonal, every circular one, is so clear. It has very quick turns; and it has this in-and-out-of-the-floor movements that are a real challenge to ballet dancers. Stillness is the greatest challenge of the work; quick actions, land on a dime; be still. Stillness is not a pause; stillness is a complete action in and of itself. Stillness takes its own energy. In those arabesques in plié, you arrive from a leap and are still in that shape. During that stillness, one does not slowly continue to lift the leg.

Getting them to do all this with the clarity and the speed they needed was fascinating and a fulfilling assignment. The shapes and the combinations are deceptively like classical ballet, but the juxtaposition of speed and still positions was nothing like classical ballet dancer is trained to do. Within the Cullberg Ballet there was a combination of ballet trained dancers and modern dancers and it had the quality of an early version of Merce’s company where there were so many different shapes and degrees of training.

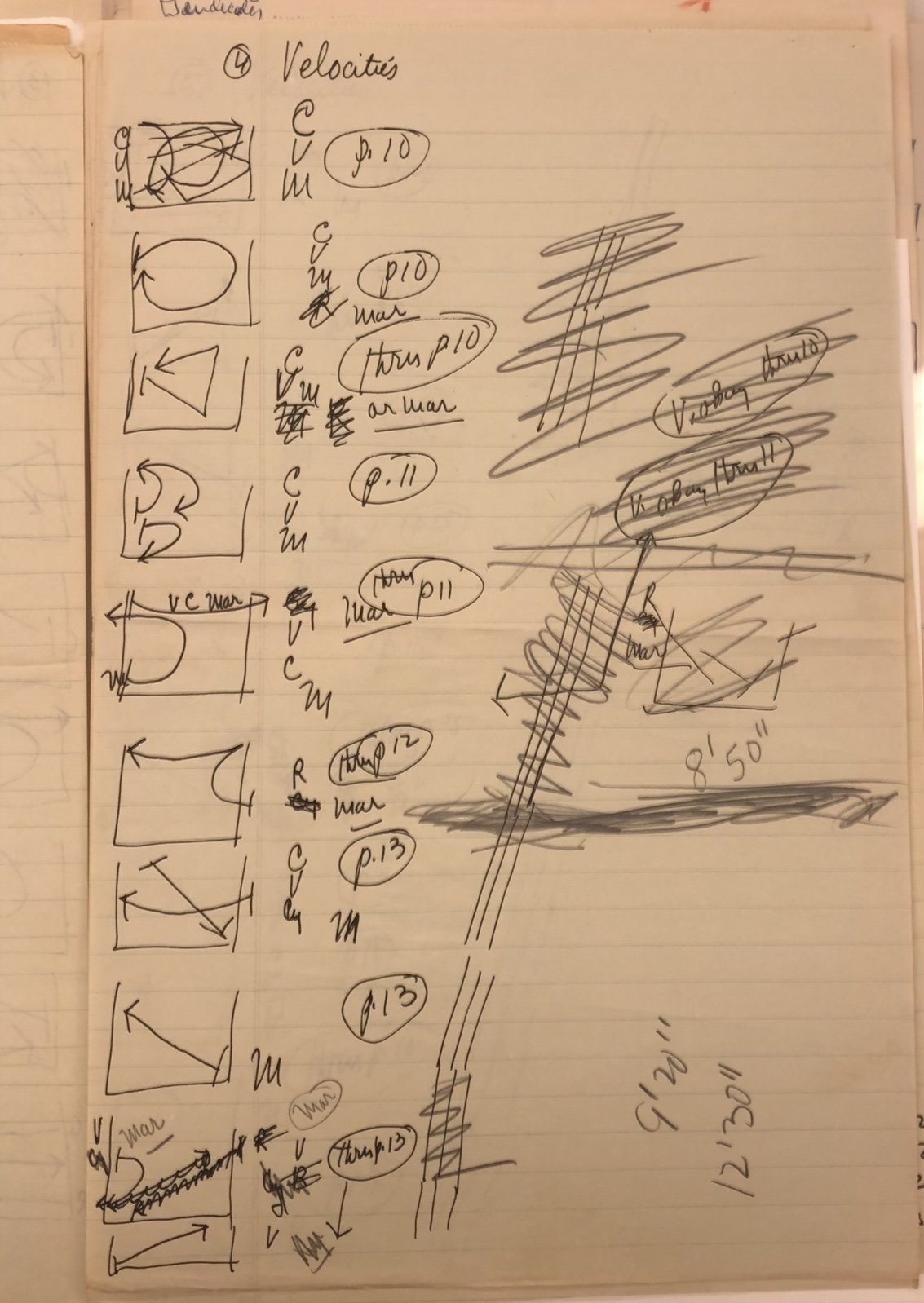

And there was no use of center or centerstage. You would cross through the center of the stage, but nothing ever landed in the center. Merce had said “It’s like the passage of birds, stopping for a moment and then moving on.” To Rauschenberg, he had said “It seems to be doing with people and velocities.”

For me, besides overcoming a “Can I do this?” feeling, Merce asked that I teach the technique first before teaching the work. That gave me a sense of the company and the company a sense of me and a trust, I think. I created a kind of camaraderie in Stockholm before teaching the work. Niklas Ek[22] had danced with the Cunningham company in 1966; I think this is probably why Merce said yes so quickly to Birgit in giving her the work. He knew Niklas could do his part - he would be dancing Merce’s role in Summerspace.

Before I went to Stockholm, I went to each Cunningham Summerspace dancer, since Merce himself had set the work on us in the workshop, to check their understanding of their part. (I ended up staying the rest of the year teaching in Stockholm. I also made a work for them called Vorspiel).

My notation is in Merce’s book: Changes.

When Merce re-set it on his company, he brought me back to teach it.

AM. And did Merce come and check what you had done?

MJ. Oh yes!!!!! Merce arrived with John to check out my work. He was very pleased, seem touched! He said it was fantastic. But it was wonderful to watch how he made the tweaks as well. I was relieved he came to do that both for the work and for me to continue to learn from him.

They - he and John - stayed a couple of weeks. I spent a great deal of time with them then – talking, listening, mushroom-hunting in Skägga. It was my first time that I had what might be considered “leisure time” with them.

( I remember peeking through a key-hole watching Merce give himself a class to Stravinsky before we worked with the Cullberg Company.)

In 1970 I moved back to San Francisco; In 1972 I went to La Rochelle, France to teach Summerspace to the Théâtre du Silence and in 1974 they came to San Francisco to continue learning the work before performing it in Paris. In 1974, I also taught the work to the Boston Ballet.

Additionally, Merce came out to San Francisco to teach two-week workshops for me a number of times. Our relationship shifted, as one might imagine, with distance and time, and around 1976 it became clear that someone who was working with Merce and at the studio and in proximity should be the person to teach his work to others.

AM. When did you realize that Merce and John were a couple away from work?

MJ. In those days, one didn’t talk about who was or wasn’t a homosexual or a couple, but yes, it was known or felt; I knew from the outset.[23] At UCLA in ‘63, it was also very clear to us that Merce and John were a couple.

Nonetheless it was very interesting to me to observe, even in my relative youth, the heterosexual naïve dynamics around Merce. That was an era when women in general, and some in the company, felt they might be the one to convert him to being straight.”

AM. I’ve often thought that Merce was, if this expression makes sense, a closet heterosexual.

MJ. I agree! One felt that in the room with the women dancers… his deep love for them.

AM. You mentioned earlier the dynamics onstage between him and his male dancers…

MJ. I observed that most, of course, with Chris Komar.[24] His relationship with Merce was in every way the most complicated, I suspect.[25] He was being groomed, groomed to take over – whatever that meant.[26] Then he fell ill with AIDS, which had a profound effect on everyone, management and the dancers.[27]

With Art Becofsky in his role as Executive Director and his love of Chris also felt, everything was made very complex in managing the company moving forward from that point for Merce and the dancers.[28]

Once I moved to San Francisco, it was clear to us both that something had changed. In 1976, we formally said “I’m living here; I’m not teaching your current ongoing shifting technique.” And by that, I meant, I am not in class every day seeing how you are shifting focus or emphasis, so it doesn’t seem appropriate to say I’m teaching Cunningham technique; so I started to say: “Cunningham-based” technique. It was a kind of cut-off moment, a professional divorce one might say.

Merce didn’t do goodbyes very well!!!!

By 1979, I had a child, Leslie. Merce was very sweet and attentive to her: he sent her bird pictures, fairly regularly.[29]

He came out to San Francisco, and taught workshops in my studio.

In 1974-1976, before we “separated”, his visits really catapulted San Francisco out of its provincialism. I had hundreds of people in class. I started a school to address teaching different levels and the interest in his technique.

There were four or five dancers working for me in San Francisco whom he saw in those classes who he offered work to and took into his company. We eventually laughed about that – his taking my dancers into his company! - it wasn’t so agreeable at the time. They were Karen Attix[30]; Lisa Fox[31]; Graham Conley[32]; Megan Walker[33]; Judy Lazaroff[34].

Douglas Dunn[35] had worked with me earlier- 1969 – my first duet was for June Finch and Douglas. Douglas took my classes regularly. Merce saw him there.

AM. And Joseph Lennon?

MJ. Yes, Joseph Lennon[36]. And Ellen Cornfield.[37] With Joseph Lennon, it was always obvious he was heading for New York having been raised here and we laugh at how I encouraged him to get out of here.

AM. Your teaching of Cunningham technique at the studio: did Merce invigilate or examine you? Or did he give you freedom?

MJ. I had complete freedom. I think it was understood I wasn’t going to teach Limón technique. Merce knew I was studying with him. My classes were my own, though, because they had my background quietly embedded in the movement as well - a Limón character, a Limón flow. But I embraced the clarity, the insistence on clarity, in Merce’s technique.

AM. Looking at Merce’s work and his company over the several decades you watched it, did you observe any particular change? Or what change struck you as important?

MJ. The most dramatic change was the kind of dancers to which Merce felt attracted. He became interested – this was my observation – in less complex human characters. You didn’t find him gathering a vast array of body types or personalities. He was attracted to the facility that ballet training brought.

The company became full of phenomenal humans with vast technical ability. I think it took Merce time to adjust to that.

And then the necessary transition to using computers given his facility was less facile. But in his last ten years he made a transition to allowing people to live in their own bodies more fully again. It had a formality and a freedom.

AM. …I was lucky that I was a friend of David Vaughan.[38]

MJ. When I danced with Gus Solomons in New York, we did a piece at the Delacorte called “…simply this fondness” with David Vaughan reading Gertrude Stein as our accompaniment.

David was our education. That was a part of studying at Merce’s studio. If David mentioned an art exhibition or a book, that would be something we felt we must go and see or read. It was all about participating in the cultural and aesthetic life in a way that David thought you should. We were in David’s book club, so to speak.

When there was a Horse’s Mouth (Tina Croll and James Cunningham’s invention) to celebrate Gus Solomons, Jr., David was a part of it. I flew to New York to perform in it and David performed as well. We both referenced, in the performance, the Delacorte duet.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

II: 2019.vii.24

AM. You wanted to speak of your other experiences in staging Summerspace.

MJ. My experience in staging it for Boston Ballet was the least satisfying somehow; I think in retrospect it might have been because I was so clearly not a ballet dancer and perhaps not as fully accepted by those dancers as a teacher of Merce’s work; it’s hard to know; but the atmosphere around learning his work didn’t feel as lively – the dancers didn’t feel as excited as they had felt in Sweden and eventually in France. Boston Ballet did ask for Summerspace; Merce asked me to stage it. But unlike Stockholm and La Rochelle (Théâtre du Silence), he prepared the way by teaching some of the material to the dancers and left me to fill the details, so to speak.

I have two lasting memories of that Boston experience. This was 1974. One: of the three experiences I had teaching Summerspace, the Boston company was the most ballet-oriented, oriented in that they did not have any modern repertory at that time anyway. Cullberg[39] already had many contemporary works; she was very interested in that so her dancers had that predisposition as well. Today her company (although she is deceased) is entirely contemporary.

So the teaching of Merce’s vocabulary was the most challenging to the Boston Ballet. It was quite new to them to move in and out of the floor and no doubt it felt like there was not much to do – so sparse was the action. It was new to land in a position and be still – no embellishment accepted. Many of the movements that might appear to be simple actually are very demanding, and was counter-intuitive for those ballet dancers: the curve of your arms as you lift your leg might appear to be as you were trained but it is just off – and the difference makes the difference in the work. But that WAS 1974 and today Ballet dancers are trained to do modern work often.

The details were so pure and so spare; it was very hard for Boston Ballet. I have no memory of whether they enjoyed it. You can read the historic details in David Vaughan’s book.

This weekend, I watched the Charles Atlas film of the 2002 Cunningham company dancing Summerspace. I thought “Oh – how interesting to see how the generations since its inception, have changed it – not intentionally of course – but nonetheless it has morphed slightly over time!” I observed quite a number of shifts in the choreography since my time of teaching it. They are subtle but do make a difference in the mystery, the rhythm, I think.

Two: I remember sitting at the Boston premiere with Merce. As people walked out, I felt his agony; he was not a happy fellow that night. It’s always hard to watch one’s work from the audience, but to watch people leave in droves – not easy. Summerspace was not a work that tended, in general, to have that effect on audiences. Winterbranch, yes: the music was so loud, the lights shone straight in the audience’s eyes, so, although I loved it, I could understand an audience feeling assaulted. But to see people leave during Summerspace was surprising.

It seemed it might have worked better if Carolyn Brown had taught the Boston Ballet. I’m not sure why Merce didn’t ask her. Perhaps that just didn’t interest her at that time.

In Boston, I felt a reluctance - a push back of some kind. For me, the Boston experience was unlike the one I had at the Cullberg Ballet and Théâtre du Silence, where I was welcomed with joy and eager anticipation: they loved my classes (although memories are tricky) and learning Summerspace. In Stockholm, I also made a work of my own - Framåt (Forward) - for the Cullberg Ballet after the Summerspace premiere.

AM. So tell me of your experience with Théatre du Silence.

MJ. Again, Merce asked me if I’d be interested. Of course I was thrilled and the usual nervous. A new country; a new language. So before I went to La Rochelle, I made a commitment to learn as much French as possible. I had three months of conversational French with a wonderful woman; we spoke only French. She was also a dancer so I could concentrate on what I needed to learn to be accurate about the body – gesture and nuance.

I had also learned enough to speak Swedish in class and rehearsal but then everyone spoke English so there was little need. In La Rochelle it was absolutely necessary to have some command of French. I and they were so pleased I had made that effort - and given I was not in the Paris, but further South, English was not an option. They were kind to me around my pronunciation.

Brigitte Lefèvre[40] danced the Carolyn Brown role; Jacques Garnier[41] the Merce role. That was the first foray of the French to acquiring any Cunningham repertory. Of course I didn’t know how this adventure would eventually unfold, and the importance to Brigitte who became so influential in France as the director of the Paris Opera and then the Minister of Culture and to Jacques who would go on to start the modern within the Paris Opera. My friendship continued with both of them. Unfortunately and sadly Jacques died of AIDS but Brigitte, who recently retired, remains at work in all kinds of ways.

For me personally, it was wonderful. They were such an open group of dancers – welcomed me with such warmth. (I’d danced in France with Twyla and taught at the American Center, but I hadn’t been that far South. I was there for six weeks. Such a beautiful town.)

The premiere was to take place at the Théâtre de la Ville in 1976; After I taught the work, I returned to San Francisco, where I continue to live.

Soon after I returned, they called me. “Could they come out to San Francisco and continue working on it? I said “Of course!” Merce had been out to San Francisco teaching workshops a number of times by then and of course I wouldn’t do anything without his permission. He approved.

They had money: the French government was generous in those days. I hired a translator. They arrived. We rehearsed. We had some students watch the showing they gave. We finished; they went back; the premiere took place in 1976. An inspired time.

An aside of sorts. My husband, Al, went with me to La Rochelle. We became very good friends with Jacques and the company folks. Jacques in particular took us further south to meet his family – his brothers, his mother. We embraced one another as friends. Jacques’s death (in 1989) was a huge loss for me and Al.

Additionally, Brigitte and I had this wonderful connection for many years – and whenever I was in France we would meet. (Brigitte has no capacity with English, which I secretly loved since my French is awful; when we meet for lunch, it’s just hysterical. But we’ve kept the friendship, despite or because of our lack of being able to communicate!)

Merce went to the Théâtre de la Ville for the premiere. He and I were never together with the company, as we had been in Sweden. He trusted it would work although he did work with them in Paris (I don’t know for how long). Sweden, as it was the first time I had taught his work, it was essential that he could to check the “translation.”

Brigitte and Jacques were impeccable technicians. The other dancers had considerably more eclectic trainings. I wrote to Merce that some things needed to be altered, because of the nature of the dancers’ skills. I asked Merce – since it was finally his decision to make. They were small but there were some. And, if he didn’t agree, he could always change them in Paris.

I mentioned to Merce how many turns there are in Summerspace., which can be hard for non-ballet trained dancers. (Merce just said, “That was Judith Dunn. She didn’t know how to turn, so I gave her lots of turns.” That was very Merce!)

So my whole experience with the Théâtre du Silence was wonderful.

AM. Did Merce speak of Asian philosophy, of Zen?

MJ. John, yes; Merce, no. And John only a little. When we were in Sweden, mushroom hunting, some of that emerged.

AM. Which Judson dancers do you remember taking class with Merce?

MJ. Lucinda Childs[42], Meredith Monk[43], Laura Dean[44], Yvonne Rainer[45], Deborah Hay[46], Douglas Dunn.

Douglas Dunn I had known in San Francisco; he grew up on the Peninsula; we met at an American Friends Service Committee retreat when we were teenagers; he went off to Princeton as an English/Philosophy major; I went to Juilliard; we stayed in touch during that year and from that time on. We reconnected in New York through his studying with me, his eventual work with Merce and my own work in which he danced.

I remember teaching a class that Yvonne and Meredith both took. In the arrogance and ignorance of my youth, I mistakenly thought one had to have a certain kind of technique to dance, to make work. I looked at this odd creature Meredith Monk and I thought, “How

will she be able to do this? She’s never going to be a dancer!” I hope she never heard my private thought! Of course, she became an example of the exception to every rule one shouldn’t follow, of how the mind and the aesthetics and philosophy define what a body can do and what she came to invent was of course unique and necessary. I was twenty-four! I knew nothing. Later, luckily, I came to realize my ignorance with an abundance of embarrassment.

AM. Can you say what Merce’s influence on Twyla Tharp was?

MJ. Twyla was and is an extraordinarily rigorous intellectual with a kind of hidden humanity about her. Her early work was really about exploring in some ways that which Merce had encouraged – although she would not herself articulate this, but she took one

idea like Tank Dive and insisted it just be fully itself – no frills or extras or incumbrances.

I find it remarkable that no choreographer who studied with Merce has made work that looks/looked like anyone else’s especially that of Merce’s. Lucinda’s work does not look like Trisha’s or Gus’s like Douglas Dunn’s or Meredith’s or Yvonne’s….!

Trisha Brown, Twyla Tharp, Meredith Monk, Steve Paxton are/were so different from one another. But they all had some relationship to Merce, some mercurial ongoing, even mysterious – one might say private connection to his spirit. He gave them, without even knowing he was doing so, the sense of trust in the rigor of one’s own mind. Trust your own intellect, your own emotional circumference, your own aesthetic input.

Merce said “If you find that interesting, pursue it.” This was before Sara Rudner was on board and I think we all know her influence on Twyla’s aesthetic and decades of work.

Note about performance:

We worked for days on a work with Twyla – Sara and I - before we found she was going to put a wall up between us and the audience, a large wall. We thought “What the f..k?” That was Twyla being influenced by Merce in some way (letting us know, as Merce did with music, only at the time of performance hearing it for the first time). She had an idea, and she followed it with the rigor that Merce would have encouraged.

Merce and John gave a kind of “permission” to everybody to let who they were in their individual lives, in relationship to their worlds (background and foreground) be reflected in the form and content they chose to follow. I think this is why John in particular but Merce too so loved Elizabeth Streb’s work. It is/was so authentically her.

AM. What are your thoughts on the scores, the music, Merce used?

MJ. I first heard them in 1963 at UCLA. The first concert was Aeon (1961 – score by John Cage). Story(1963 – score by Toshi Ichiyanagi). Crises (1960 – score by Conlon Nancarrow). – a real variety. Again, I could feel a politics within that arch.

There were sound scores that I found more or less interesting. But I loved being in the theatre with that kind of music, that velocity.

It made so much sense to me – the volume, the intensity – it seem to match what I felt, who I was then, how I was trying to put things together for myself at that time. And to be freed from a narrative, to let the movement and the “story” unfold like life, without a

linear frame, what a relief.

I was one who never raced from the theatre because it was so loud. For me it was not!!

I did, however ask myself “To what degree was Merce comfortable with what he heard? Did he ever say privately, ‘Yikes!!!! I wish I had heard that before we went on, or ….?’” I don’t know the answer! Was it ever disruptive to him? Did he find it totally satisfying? I found it totally consistent with who he was and his life with John Cage that the music was what it was. I had also notated Field Dances (to a Cage score) and Septet (to Satie). I just remember how he moved between the notes of Septet and how the quiet was impossible to notate.

His dancing had this extraordinary capacity to show, but not show off. It was so completely present and then like lightning it left its mark but he had already moved on.

AM. May I ask you how you react to Carolyn Brown’s book?[47]

MJ. I find it extraordinary in some ways. I think there are generations of young people who will be lucky to read this account of the very beginnings of a company before grants and even “being paid” came into being, but to hear of the early years of these remarkable people – what a treasure. It’s a remarkable piece of work. It’s an overwhelming feat of detail and

memory, an invaluable resource. What does it mean to be in a company just for the love of dance? Just a love affair with the maker of the work? And as with all very personal accounts, what’s left out is as revealing as what’s left in.

I have file cabinets very full only of my correspondence with Merce. Carolyn and I were friends at the time. In 1979, I had a child. In the last two months of pregnancy, I had to be in bed, so I invited Carolyn to come out and work with my company. She made a lovely work; and she taught daily. It was a treat for everyone.

Carolyn was my teacher for years and years and I learned so much from her – this creature who was so different that I was – from such another part of the world and world view and, even though my youth prevented me from knowing it at the time, I am privileged to have been around what she knew. She, like all of us, have our versions of what is important to know, what technique is important to study. Carolyn was one way to understand Merce, while Viola Farber, was yet another.

AM. I agree with you about the book’s virtues, but I also find it a startling example of passive aggression. At the very end, when she has gone to see Merce’s latest work in Paris, she congratulates him and he says “I love you.” She ends the book there, saying “And, at last, I believed it was true.”

MJ. Yes, that’s such a curious and inexperienced revelation of the psychological understanding of how people work. Merce’s works for her, his profound focus on her in his work, were a statement of his love for her from Day One!

Carolyn’s book also shows you her love affair - not physical of course - with Remy Charlip. She had this need to be adored. It was continual, exhausting. If Merce didn’t give her enough reason to feel adored, she was in anguish.

AM. There are always so many psychological ramifications around all choreographers and dance companies.

MJ. Over the years, during my own therapy, I explored the many aspects of being a working artist – the privileges, the promises, the loneliness, the impulses to flee, to gather, to make family out of company, etc.. You discover the enormity of transference that can happen between “director” and dancers, the need to read someone’s affection or love of your dancing as more than that. Merce was not anyone’s father or most likely someone’s lover. He was a choreographer – with all the challenges and complexities necessary to do that work.

Thanks to Merce and his trust, at such a young age (twenty-five) I was in Sweden, then France. It launched me into a different understanding of myself and eventually my own work. I have Sweden. Being there then, launched a career in one way. It’s now been a fifty-year love affair with the country (Sweden) that continues through to this day. The work I made there was revived every few years until Birgit Cullberg’s death. And I have since returned numerous times as an advisor to the Swedish Council and to present my own work in 2016 and 2018.

My husband reminded me of the significant paragraph Arlene Croce wrote about my work in her essay “The Mercists” around 1978.[48] The next year, I got a Guggenheim with a recommendation from Merce.

This life of dancing and making dances was propelled forward by the trust and insistence of Merce - that I had something to share. He needed what I knew how to do; and he knew how to make you feel necessary. It was a mutually beneficial exchange and deep friendship. Lucky for both of us. He made it easy to love him and the work and in return I felt his gratitude.

AM. Do you have memories of seeing him on your returns to New York?

MC. Whenever I went back to New York, I’d go to the studio, usually with my daughter. Merce would come out of his room, and give hugs to us both.

But there was one time[49] I arrived in the studio and Merce just glared at me and said “What are you doing here?” I was so taken aback. “You shouldn’t be here.” Whoa! Okay…, but I was startled. No warning – out of the blue. My daughter was about ten and visibly shaken.

I asked at the desk “Any clue what’s going on?” I called Robert Swinston [50]. Robert said, “I don’t know. You know how he can get.” I had a fairly honest relationship with Merce. So I wrote to him and said “What’s up? Is there anything going on? This is really unusual for you with me. Have I done something? Speak up!”

I didn’t expect to hear back, but Merce wrote. He said “Oh God, Margy, I’d just gotten bad news for the company. I was beside myself and there you were. I thought ‘I can’t be open’. I just didn’t want you there. I am so sorry!”

For him to tell me anything that personal was rare. I just wrote back and said, “I look forward to seeing you next time and hopefully things will have eased.” It was a rare moment in time. Merce being caught off guard; Merce letting me know he was; Merce asking forgiveness.

AM. Some people I’ve spoken to feel that Merce’s technique and choreography began to make a less full use of the back from the mid-1970s on.

MJ. As he was less able to move in dance, that made his technique shift I think – hence less use of the back. As he got more seduced by what ballet people could so, his use of the back did grow simpler. That had been a wonderfully unique signature of his style,

(the use of the back) in combination with the legs, from the 1960s or earlier into the mid-1970s. That’s why it was interesting to look at this 2002 film of Summerspace and see how the use of the back had pretty much gone away, especially in Viola Farber’s role. It’s very hard, this translation over the decades, so I can understand! Nuances get ironed out literally and figuratively.

Some modifications get made; subtleties disappear. Anyway, yes, I agree about the back.

AM. What are your memories of Rauschenberg?

MJ. He was with the company in that UCLA residency. And I came across him again through my visits to New York in the 1970s.

I was told that Bob was someone who went kicking and screaming through a relationship with his collaborators, but it seems he came to love his role with Cunningham for a long while – the last minute of the lights in Winterbranch, for instance. He had the idea that no medium should be subordinate. He was an imaginative wonder.

In Aeon, which I saw in 1963, he developed the décor that consisted of machinery and scrap metal: a whole new array of stuff, which I am also told the company loved having around.

I remember Bob speaking in this very free way at UCLA. It was a great joy to have him around. Unlike Jasper (Johns), who was more introspective, Bob was out there making personal connections with everyone. To us students, he’d say “Why don’t you try that, what’s to lose?” He was just very supportive of us as students. And in New York, when I was working with Twyla, he was the same – supportive and actively present. I came across him later when I worked in Viola Farber’s company with Dan Wagoner and June Finch. Viola’s relationship with Jasper was even closer than with Bob, but she was joyous with Bob when he was around.

AM. And Jasper Johns?

MJ. He was always sketching; he was always quiet. I always felt he was a very soothing presence for Merce; I don’t know if I’m right.

AM. Can you say what you value about Cunningham dance theatre?

MJ. I think Summerspace, Crises, Winterbranch, Place, RainForest, Sounddance made me feel that Merce lived in the world and that his work was a reaction, a wish, a premonition. Merce wouldn’t say or publicly talk about “where” an idea came from for a dance. But they revealed he was a human being who made things not in isolation from the world we knew…that he was affected by what was going on around him, in nature, yes, but among people, nations too.

In our Sunday talks after I returned to San Francisco in 1970, he would gossip about what he could see in the street from the studio, about people’s behavior, or those in the company he wondered about. I remember he said about one dancer: “He has no rhythmic necessity, but I love his dancing!”

I felt there was a conscious intention, despite the chance procedures, to speak to city streets and natural processes - a kind of trusting of the relationship between things. I don’t think chance was his license for chaos. It helped him control what was out of control. It allowed an order that he might not have chosen. But it didn’t choose content.

It challenged him to free himself from the strictures of his own mind. He couldn’t control the idiosyncrasies of everyday life. Chance was a way to surrender to something larger or other than himself.

It was intense: he found both joy and substance and I suspect a modicum of agony in his relationship to the working process. He was often closeted in his studio. If it hadn’t been for John (Cage), if it hadn’t been for Jasper, he really might have been a hermit; they made him be a public person. And his dancing made him even more public. Otherwise he was not a creature of the world as in IN the world. But I think he loved being out there, and that he had dear friend who made that way to the “outside” a possibility, was crucial. I’m really not sure otherwise, without John and a few others, he would have found his way to the public so to speak.

AM. And your memories of John?

MJ. I knew John before all the traveling and intensity/enormity of keeping the Cunningham company stable became to take so much of his time and energy. It was a momentary time of quiet for Merce and John. Casual encounters and dinner were possible.

On a couple of occasions when they came to San Francisco, they would stay with my parents. They had an extra room (the kids were gone).

As my husband was a criminal defense attorney, Merce and he would talk about that. Given all the lawyers in Merce’s family, there was an affinity,, a curiosity; and my father would talk with Merce about labor history. My mother was a Shakespeare scholar and poetry her guide.

Merce and John loved staying there. It was only a few times, but they did and I treasure that memory. They’d talk of Seattle, of the Labor movement in Seattle. And Shakespeare, theater.

Michael Palmer, the poet with whom I have collaborated for over 49 years, knew John and many other composers, so there were opportunities for dinners with Merce and John when here and with Alvin Curran, composer. Great meals, great humor.

John had a fantasy that I knew everything about Merce. NOT true!

III: 2021.ix.24

AM. After you made San Francisco your base, one of your links with Merce was Art Becofsky. Art spent twenty years working for the Cunningham Foundation, from 1974 to 1994: for several years in the 1970, he was company manager, after which, in 1980, he became executive director; at first he held that job with Jean Rigg, and then he did it alone.

MJ: Yes, and to this day Art works for me as an executive consultant and has been critical to the administrative organization and to helping me hone my artistic goals and strategies. Art has an incredibly optimistic approach. There is never a sigh or a sense that something one hopes to achieve is not possible somehow. Art was like that for Merce: he put Merce’s work first, and he applied his mind and heart to it with total 24/7- full-time commitment. Things darkened later, I know, but before that time I could see in Merce a lightness in his physical carriage, because he knew that Art was working so fully on his behalf.

AM. Twyla studied with Merce in the 1960s, alongside you. There’s no doubt in her mind that it was his teaching that influenced her. Did she also watch his choreography? I think I see its influence in some of the spatial organization of her 1970s pieces.

MJ. Twyla is famous for never seeing another choreographer’s work, unless she has a private behind the scenes seat no one knows about! Nobody ever sees her in the audience. Sara Rudner and I used to laugh about that. But yes, Twyla did go to some Cunningham performances in the 1960s.

AM. The whole issue of whom Merce influenced among the 1960s post-modernists is so interesting.

MJ. Well, influence itself is always mercurial, I think. Twyla listened and observed intensely and I’m certain whether conscious or not, the exposure to Merce’s thinking and work affected her own.

I think, for example, of a conversation I’ve been having with David Gordon (now deceased) over the decades: I think our conversations have been as provocative for me those I had or felt I had with Merce.

AM. Some of the New York postmoderns joined the Cunningham company, some of them wanted to but weren’t asked.

MJ. I don’t know who wanted to but wasn’t asked. But his aesthetic was so compelling and authentic, one wanted to be around and work in that world.

June Finch (now deceased) and I so wanted to be asked. We would confide in one another about how much we wanted to get into the Cunningham company. I suspect (don’t know), that June, for instance, was so invaluable as a teacher for Merce that he might want to keep her in that place.

We certainly loved the work, and would have taken any number of other jobs to have that experience, but sometimes NOT getting what one thinks one wants, propels one into other welcome surprises.

In those early years, working with Merce, although hardly a salary on which one could live without other work, there were only two or three companies in New York who paid anything. And if you got a job with one of them, you would also get unemployment pay when the company wasn’t operating.

AM. It interests me that you respond to what you call the “politics” of several of Merce’s dances. I’m like you: I see some of his works as views of the world and human energy in ways that feel political. Still. Merce always said that he avoided politics.

MJ. I think his interest in my family, given their political officiations – both communists until the Khrushchev report came out on Stalin - said something about his awareness of or notice of that part of life. I think his attraction to my mother – who was clearly left-wing, very erudite, and a Shakespeare scholar – was driven by her background and commitment to change. It fascinated him. My father was so other - a longshoreman with no formal education, but profoundly self-educated and active in Labor Unions along with a profound love of the arts. Merce just loved hearing their stories and being around that.

When I first took his class at UCLA in ’63, he came up to me and said “You must be Russian”. (Well, I am! My father’s family was from Kiev and Odessa.) But I thought “How strange.” I guess it was something about how I looked? After class, Merce wanted to know a bit about that. And so I told him about my Russian background.

AM. Did he say why he was interested in your Russian side?

MJ. He did say he studied Russian a little. He said “I can’t speak Russian, but it really interests me.”

And then I came to realize, later on, that that was something he liked to study on his own.

AM. What were the later works that mattered to you most?

MJ. “Sounddance”, “Ocean”, “BIPED” – others, too. I know that to some degree my love, respect and wonder was for those Cunningham pieces that embraced a subtle emotional territory, in the way the dancers were used and in how they interacted with each other. Works whose landscapes held tension and implied narrative nuance at an emotional level truly engaged me.

For me, some of the work, especially after he started to use the computer became more formal somehow and I was less engrossed.

AM. Did you see his last piece, “Nearly Ninety”? The dancers knew that he was making most of it without the computer.

MJ. I came to New York to see it. Yes, that was an extraordinary night!

AM. Three months before, Merce had terminated the contracts of three senior dancers. They appeared in Nearly Ninety, but left the company that summer.

MJ. I was most upset about Holley Farmer. She had qualities that took me back to the old days; she commanded the space and took charge that registered in a way that made me think “Oh, there’s a Viola, there’s a Judy Dunn.”

But you can’t ever fully know why choreographers take or dismiss dancers. I think back over the 135 dancers I’ve had in my company, and the many more I’ve auditioned and in some instances I understand why I’ve chosen someone but I also think “Why did I choose this person over that person?”

AM. Did you have inklings that Merce knew the end was near?

MJ. Yes. I made three trips to New York, having heard or knowing he was frail. For whatever reasons, I wasn’t “allowed” to visit. I can understand those who were caring for him were protecting him, but it made me quite sad to not have that “last” connection. But he clearly lives on in my body, mind and heart.

AM. When Merce announced that the company was to close after his death, after a two-year world tour, were you surprised?

MJ. I was actually surprised he thought the company should continue after his death at all. But I’m not sure what I base that on. Perhaps other people around him needed that extended period for the company, as a way to slowly let go. Certainly it was a wonderful way to keep the work and his legacy alive: an extraordinary gift to the world.

But I doubt very much whether Merce himself cared. He was about the immediacy of the interactions, the moment of making and then sharing of the work.

I should add that it’s a mistake to presume that one knows anyone, finally, well enough to say: “I think he felt…”! So that awareness of what one can’t know about another, might cancel out anything that sounds assured above.

[2] Cunningham’s main designer in the years 1954-1964.

[3] It’s interesting that Johns joined Rauschenberg, Cage, and Cunningham for this residency. At this stage, 1963, he had undertaken no official work for the Cunningham company. In 1958, as Rauschenberg’s unofficial partner and colleague, had anonymously contributed some of the paintwork to the décor for Summerspace. After Cunningham’s and Rauschenberg’s deaths, the choreographer Paul Taylor said that he too had contributed some of the paintwork.

Johns succeeded Rauschenberg with the Cunningham company in 1967, being given the official title of artistic advisor: being less naturally theatrically minded than Rauschenberg, he suggested other visual artists to design Cunningham works, although he certainly contributed to several pieces himself.

[4] Carolyn Brown, MCDC 1953-1972

[5] Viola Farber 1953-1965; also 1970.

[6] Steve Paxton, MCDC 1961-1964.

[7] Shareen Blair, MCDC 1961-1964

[8] Sandra Neels, MCDC 1964-1973.

[9] Gus Solomons, Jr, MCDC 1965-1968.

[10] Twyla Tharp, b.1941, internationally renowned choreographer.

[11] Valda Setterfield MCDC 1961 and 1965-1975.

[12] Robert Huot, painter, was Twyla Tharp’s husband until 1972.

[13] Sara Rudner (b.1944), dancer and choreographer.

[14] Remy Charlip, MCDC 1950-1961

[15] Marilyn Wood, MCDC 1958-1963.

[16] Albert Reid, MCDC 1964-1968.

[17] Cullberg, formerly the Cullberg Ballet, was founded by choreographer Birgit Cullberg in 1967. It is now described as “the national and international repertoire contemporary dance company in Sweden”.

[18] Yseult Riopelle, MCDC 1966-1967.

[19] This is now kept with Cunningham’s Summerspace notes in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts boxes of Cunningham’s notes.. AM.

[20] Pronounced with a hard G.

[21] Kay Mazzo is among the members of the 1966 New York City Ballet cast who vividly remember Cunningham himself teaching them the movement, but not Brown at all.

[22] Niklas Ek (b.1943), son of the Swedish choreographer Birgit Cullberg, and brother of the choreographer Mats Ek (b.1945).

[23] David Vaughan, long-term Cunningham archivist and school secretary from the 1950s, stated that he did not realise that Cunningham and Cage were a sexual couple until the 1964 world tour. He had guessed that Cunningham was gay, but not that he had a permanent partner – until he, Vaughan, had to book the hotel rooms for the 1964 world tour, when everyone was placed in rooms for two.

[24] Chris Komar, MCDC 1972-1996

[25] Others observed signs of a sexual and work intimacy between Cunningham and Komar in 1972 and again from 1985 onward into the 1990s.

[26] In 1993, Komar, previously assistant to the choreographer, was appointed assistant artistic director.

[27] Komar died of AIDS-related causes in 1986.

[28] Art Becofsky worked for the Cunningham company and Cunningham Foundation for twenty years, between 1974 and 1994. His two main posts were company manager and, later, executive director.

[29] Cunningham’s drawings of birds and animals became a major diversion for him from the 1970s or earlier. They have been exhibited, both during his lifetime and later.

[30] Karen Attix, MCDC 1975-1977.

[31] Lisa Fox, MCDC 1977-1980.

[32] Graham Conley, MCDC 1977.

[33] Megan Walker, MCDC 1980-1986.

[34] Judy Lazaroff, MCDC 1981-1983.

[35] Douglas Dunn, MCDC 1969-1973.

[36] Joseph Lennon, MCDC 1978-1984.

[37] Ellen Cornfield, MCDC 1974-1983.

[38] David Vaughan, critic and historian, was an integral member of the Cunningham enterprise from the late 1950s onwards; he became its resident archivist.

[39] Birgit Cullberg (1908-1999), Swedish choreographer.

[40] Brigitte Lefèvre (b. 1944) is now best known as the long-term artistic director of the Paris Opera Ballet in 1995-2014. In 1971, she and Jacques Garnier co-founded the Théâtre du Silence.

[41] The French dancer Jacques Garnier (1941?-1989 ) had studied with Cunningham and others in New York before co-founding the Théâtre du Silence., In his later years, he later headed the contemporary dance troup of the Paris Opera Ballet

[42] The choreographer Lucinda Childs, b. 1940.

[43] Meredith Monk (b.1942), musician, film-maker, and creator of dance theatre works. She sometimes composed music for Cunningham Events.

[44] The choreographer Laura Dean (b.1945), aj important exponent of dance minimalism, was active until 2001.

[45] Yvonne Rainer (b.1934) was a central figure in the emergence of New York post-modern dance in the 1960s.

[46] The choreographer Deborah Hay (b.1941), still active, danced briefly with MCDC in the 1964 world tour.

[47] Carolyn Brown: Chance and Circumstance, Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham, 2007.

[48] Arlene Croce, “The Mercists” The New Yorker, April 3, 1978. See Croce, Going to the Dance (1982), Knopf, New York, pp. 67-72.

[49] This anecdote is probably belongs to some date between 1993 and 2007.

[50] Robert Swinston, MCDC 1980-2011, assistant director of the company 1996-2011.

@Alastair Macaulay, 2022

1. Merce Cunningham in Summerspace (1958), probably in the 1960s. Photo: Jack Mitchell.

2: Margaret Jenkins.

3: Merce Cunningham’s Aeon (1961), designed by Robert Rauschenberg. Left to right: Carolyn Brown, Steve Paxton, Merce Cunningham.

4: Merce Cunningham’s Summerspace (1958). Viola Farber (upright), Carolyn Brown (on floor).

5: Margaret Jenkins, Birgit Cullberg, Merce Cunningham, at a dinner given by Cullberg at home.

6: Cunningham and Jenkins in Marbella, Spain l. See 7.

7. Jenkins, Cunningham, and Jenkins’s husband Al Wax with their daughter Leslie (left) and two other young friends. The photograph was taken in Marbella; Spain, where Cunningham and company were dancing and Jenkins and family were on vacation.

8: Cunningham teaching in Jenkins’s San Francisco studio.

9. The cover of Jenkins’s notation score of Summerspace, now in the collection of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. When I first interviewed Jenkins in summer 2019, she had no idea what had become of her score, which she had given to Cunningham in the 1970s. He had kept it with his own Summerspace notes. After his death, it passed to the Library, where I photographed these few of its many pages in early 2020. Only two years later, in February 2020, did I remember to tell Jenkins that her score was in good hands.

10: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

11: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

12: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

13: In this page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace, the names refer to Carolyn Brown, Viola Farber, Barbara Lloyd (Barbara Dilley), Albert Reid, and Sandra Neels. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

14: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

15: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

16: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

17: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

18: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

19: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

20: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

21: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

22: A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of Jenkins, the Cunningham Trust, and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

23: A page from Cunningham’s own 1958 preparatory notes for Summerspace, indicating the ways in which he planned to use chance as part of the composition of this work.A page from Jenkins’s notation score for Cunningham’s Summerspace. Reproduced here by kind permission of the Cunningham Trust and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

24: Another page from Cunningham’s own 1958 preparatory notes for Summerspace, using Velocities as his working title. It is characteristic of Cunningham that he used one title till well into composing the dance in his notes. As he discovered more and more about the work he was creating, he would then choose the eventual title. In this case, he learnt early on that Velocities was about a new use of space; only later did he find that it had the atmosphere of summer. As a rule, when he commissioned designs and music from painter/designer and composer; the eventual title was among the very few things he would tell them about the new piece; he had yet to begin rehearsing it with his dancers.

Reproduced here by kind permission of the Cunningham Trust and the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.