The Masked Ball of Ballet22

The Masked Ball of Ballet22

by Alastair Macaulay

December 2020 is still young. The world is still quasi-immobilised by the pandemic. And yet twice already this month I’ve been contacted by new ballet companies who are changing the art form from within.

The companies are Ballet de Barcelona (which opened last year and has already performed to thousands), and Ballet 22, a company of the San Francisco Bay Area, which opens tonight (December 11), on line. Not only on line but in masks! I write after being sent an advance vimeo of tonight’s program, which runs at just under fifty minutes, with some snippets of introduction and documentary framing six dance items.

Throughout this century, it’s become increasingly obvious that ballet has three crucial points on which to change its act: race, gender, and sexuality. About race: dancers from Janet Collins and Arthur Mitchell to Carlos Acosta and Misty Copeland have already broken barriers, but it’s evident that there’s way to go. About sexuality: it remains bizarre that an art form that has an increasingly open gay quotient of practitioners and audience admirers remains largely stuck in a rut of Boy-Girl Prince-Princess behavior. (Yes, the last ten years have seen several windows of same-sex partnering opening up, but too few and too cautious.) About gender: ballet is - I’ve been saying this in print since 1985 - the sexist art, the one art predicated on the dichotomy of the sexes. The man must do the partnering; the woman must go on point; the positions may not reversed. Yet we live in a world where many women support their menfolk, where equality in the workplace has been long a goal (and sometimes an achievement). How many signs are there in ballet today of women doing the workload? or living the single life? or of men marrying one another? Most ballet people lead liberal lives offstage, conservative ones onstage.

And there’s a fourth issue: body-types. Big leg muscles, short men, super-tall women - ballet has had limited room for any of those.

Ballet 22 and (to judge from an unfinished trailer I’ve been sent) Ballet de Barcelona solve these four problems as directly as opening a bottle by breaking its neck. Ballet 22, I should add, is all male. (I hope an all-female sister company comes along soon. Ballet de Barcelona seems set to fill out the gender spectrum.)

The Ballet 22 men dance on point, sometimes wear practice tutus, but don’t pretend to be women. The company’s tone is set by its artistic director, Roberto Vega Ortiz (who employs the he/him pronouns, and works with a woman executive director, Theresa Knudson (she/her): Vega Ortiz, originating from Puerto Rico, dances in each number without upstaging his colleagues. He and they make the Ballet 22 experience simply joyous, exuberant, and formal. You neither need nor want to know whether its performers are gay.

They’re just dancers, men who love the expansiveness of the ballerina vocabulary and the powerful danger of pointwork. Some of them have somewhat ballerina hair; tutus are worn in some contexts. But these men refuse to poke fun at either femininity or ballerinadom; they wear no makeup; and they indulge in rather less camp than much of the ritualised heterosexual behaviour that still characterises much grand ballet. As ballet theatre, this is nothing like Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, the world’s most famous drag ballet company since 1972. Ballet 22 makes no jokes. It has such honesty that I suspect “the Trocks” will subsequently seem all too laboured, while much other ballet may look fustian.

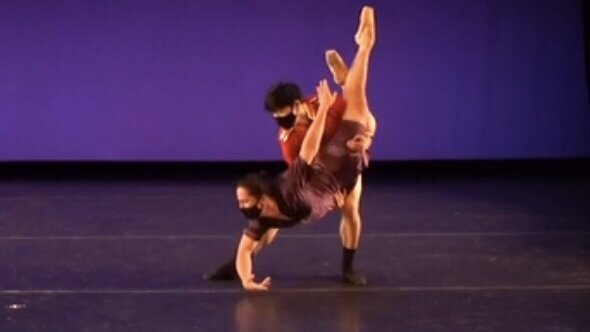

This opening Ballet 22 program should be called A Masked Ball: its dancers are all masked – and they’re having a ball. The most fascinating items are the most familiar: yes, these men dance the Nutcracker and Swan Lake adagios, in versions of the traditional Lev Ivanov choreography. The Nutcracker number, filmed at San Francisco’s ODC Theatre, is the Sugar Plum adagio (here called Fritz’s Dream Pas de Deux), Vega Ortiz himself dances the Sugarplum role, with a maroon practice culotte outfit (bare thighs and calves) and no tutu. He’s partnered by Donghoon Lee (relatively formal in a red jacket, but with practice underwear and bare legs). They dance with potent respect for each other but no pretence of love. Near the end, there’s a fabulous surprise: they take turns to catch each other in fish lifts. This is so fluently achieved that you hardly realize how subversive it is. Vega Ortiz is the first to catch his partner; in the next phrase he throws himself into Lee’s arms with no change of mood. I laughed out loud at the naturalness of it. The masks actually confer a new mystery on the whole adagio, but these men cast no languishing glances from behind them. This is a Sugarplum pas de deux without artifice; you feel how calmly the dancers relish their material.

The Odette adagio, danced in studio conditions by four couples - taking turns - is called the Swan Lake Pas de Huit. At the end, the four couples all end together, using the 1877 version of the music as in the Balanchine one-act version. The first Odette is Duane Gosa, African American, wearing a simple white tutu; Evan Ambrose, his Siegfried, wears shorts. Here and with later couples there are tiny infelicities of partnering, gallantly solved, and yet everyone’s manners are so simple that the mood is unbroken. This isn’t an emotional Swan Lake - though Gosa throws both arms forwards in his opening penchée. It’s a classical one, with the movement saying all that needs to be said.

When Ashton Edwards (another African American Odette, in a black tutu) and Lee (Siegfried) take over for the lifts, the videography (by Lázaro González) is so candid that we watch the first lifts in profile, really seeing for once how low Siegfried squats in plié. Vega Ortiz, in a more or less masculine haircut , is the third Odette (admirably partnered by Joshua Stayton), Gilbert Bolden III the fourth, tallest, and most powerfully built (with Christopher Kaiser as his valiant Siegfried). These differences in body type don’t shatter the mood. Every dancer is so strict with the steps that it’s clear he serves the choreography.

Of the rest of the program, Stayton’s Juntos (2015) is the most accomplished. It was made on women as well as men, at Tulsa Ballet II. In this masked 2020 format, however, it becomes a neatly exercise in masked-ball gender ambiguity. Its mood is brisk, cool, piquant. The “male” roles are dressed in black T-shirts and jeans, the “female” one in black tutus and long-sleeved tops. Look carefully and you see some dancers switch between male and female roles. This, however, is a light study not of androgyny but of human variety.

Two short works, Metamorphosis (to Philip Glass music) and Before the World Ends (music by Residente), choreographed by the dancers, are filmed in a variety of locations. Compositionally they’re unimportant; but the outdoor contexts have real-life charm, while the dancers are always showing us steps, movement, phrases. When you see pointwork danced by a man wearing nothing but shorts against a large landscape, you wonder if its associations haven’t permanently changed in your mind.

The closing item, Omar Román de Jesús’s Mi Pequeñito Sueño, is a harmless misfit. Seven men do a range of lifts, torso movements, flops, sits, and falls in black jackets and billowing white tutus against much side-lighting. Though they do that perfectly well, the rest of the programme makes it look sophomoric – and makes us want to see them dancing the more rigorously classical styles they do so juicily.

No, there’s no new Balanchine in this program. But it feels necessary, as if these men’s devotion to dance couldn’t wait for the right enlightened genius. In particular, the Nutcracker and Swan Lake adagios open up new realms of possibility and honesty. You want this company to tackle more repertory at once, and for other companies to take note of their clean objectivity of style.

Since Ballet de Barcelona includes women, its programmes will differ importantly from Ballet 22’s. If *they’re* as good as this Masked Ball, the whole art form will be enlarged.

See www.ballet22.com/events . There are fourteen ticketed showings between December 11 (5pm) and December 20th (8pm).

Roberto Vega Ortiz and Donghoon Lee in the Ivanov “Nutcracker” pas de deux

2: A second later in the same adagio, Vega Ortiz and Lee

3: Vega Ortiz, though otherwise dancing the Sugarplum choreography, catches Lee in one sequence….

4: …whereupon Lee catches Vega Ortiz in the next phrase.

5: Vega Ortiz in the closing phrases of the sugarplum pas de deux, partnered by Lee

6: Ortiz and Lee end the “Nutcracker” pas de deux side by side

7: In the “Swan Lake Pas de Huit”, Duane Gosa takes Odette’s développé en avant with the support of Evan Ambrose

8: Gosa and Ambrose

9: So candid is Lázaro González’s videography that we see the first lifts of the “Swan Lake pas de huit” in profile, with Donghoon Lee squatting to lift Ashton Edwards

10: Vega Ortiz as Odette partnered by Joshua Stayton’s Siegfried

11: Roberto Vega Ortiz as Odette, partnered by Joshua Stayton as Siegfried

12: The four couples of the “Swan Lake pas de huit”