Third position! Fifth position! Turnout of upper and lower body! and much more. Historian Moira Goff answers questions 40-58 about baroque dance and ballet.

Moira Goff here continues the conversation begun in summer 2021 about baroque dance. Its earlier two parts may be found on this website; Goff’s own blog, Dance in History, is a rich trove of thought and research. AM.

Macaulay 40. You’ve been concentrating on the English and French dances of 1650-1750. That period of a hundred years includes so much, starting with the galvanising involvement of Louis XIV in dance, in ballet, in the Royal Academies of Dance and Music, and in the commencement of professional dancer in ballet’s leading roles. Can you talk at all about ballet before Louis XIV?

There had been ballets de cour in France - ballets danced by royalty and aristocracy for the public - going back to Catherine de Medici. I suspect something similar had occurred in some of the courts of Italy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The tradition went on, perhaps sporadically and perhaps with increasingly young performers, across Europe into the eighteenth century: there is a famous painting <1> of Marie-Antoinette (not yet ten years old), dancing a ballet with two of her brothers at Schönbrunn in 1765: they were children of the Holy Roman Emperor and the Empress of Austria.

First, am I right to say that what happened in the French court in 1650-1670 transformed courtly dancing across Europe with lasting effect? If so, am I right to believe the transformational innovation was the introduction of turnout - with five turned-out positions of the feet - as a basis of style? How new was this? Was turnout already used, but not as a crucial central feature?

Goff 40. The influence of French dancing and French court ballets was strong throughout Europe well before 1650, although that dancing had itself developed from a variety of European styles and techniques (particularly from Italy). I haven’t done a lot of work on the French ballets de cour during the reign of Louis XIV, but it is obvious that they enabled a small group of gifted dancers and dancing masters (including the King himself and some of his courtiers) to work together on one or more ballets each year over more than 20 years. This must have provided fertile conditions for the development of the art of dancing, including the use of turnout to achieve a particular style and facilitate the performance of some steps, among them those requiring virtuosity. This period also saw the codification of the five positions as well as other facets of technique, for example the principle of opposition of the arms. Such codification also allowed dancing masters to establish a fresh vocabulary of steps and to develop ideas of ornamentation, leading to the extensive classification of steps and their many variants by Feuillet in Chorégraphie. I am not sure how important the increased use of turnout was in and of itself, although it was certainly a fundamental component of the technical developments during this period. The ballets de cour of 1650 -1670 deserve fresh, wide-ranging, detailed and open-minded research which I’m sure could tell us much that we don’t yet know about the development of dancing over that exciting period.

Macaulay 41. We tend to talk of turnout as something that happened only beneath the waist. But the arms of baroque ballet seem thoroughly turned-out too. In the twentieth century, Balanchine would say “The body has two halves, but not upper and lower: the body is centrally divided right and left.” Balanchine’s point was that, in turnout, the whole body turns out from the spine. There are vital points of style here within the torso that the notation and even the dance manuals may not illuminate, but what comments do you have?

Goff 41. I have often thought that Balanchine was, somehow, able to draw on steps and techniques familiar in baroque dance. I assume that this comes from his original training in Russia as a dancer; and it would be interesting (and perhaps illuminating) to trace his dance lineage in some detail. His observation about the division of the body into left and right can be traced, although it is not fully articulated, in the early 18th-century dance manuals. I think far more attention needs to be paid to the torso as we continue to explore the reconstruction and recreation of baroque dance, because its strength and flexibility are fundamental to good technique.

Macaulay 42. A curious point about the five positions is that second position takes the body sideways, fourth forwards. Does this say that travelling sideways was more important than travelling forwards? Or does it say that the maximum openness and exposure – turnout – of second position was even more vital than forward motion?

Goff 42. The spaces for dancing, on stage as well as in the ballroom, and the choreographies created for them indicate that sideways movement was as important as travelling forwards. I have never really analysed choreographies from this standpoint, although it is definitely significant. Travelling sideways on a track that takes the dancer away from the presence and past spectators to either side, allows him or her to continue facing their audience as they move. Travelling forwards would cause them to turn away very quickly as they passed those watching from the sides. It is worth repeating that, even on theatre stages, dancers were often all but surrounded as they performed. I think that there was a balance to be held between forward and sideways movement, as choreographers sought to exploit their dancing spaces to the maximum.

Macaulay 43. Today, third position has largely gone missing. The eminent Cecchetti teacher Richard Glasstone, well aware of its disappearance or erosion, has spoken of its beauty in dovetailing the ankles and as the position through which the feet pass in entrechats. (Some modern teachers would prefer an emphasis on fifth position in entrechats.) Can you speak about third position in baroque dance?

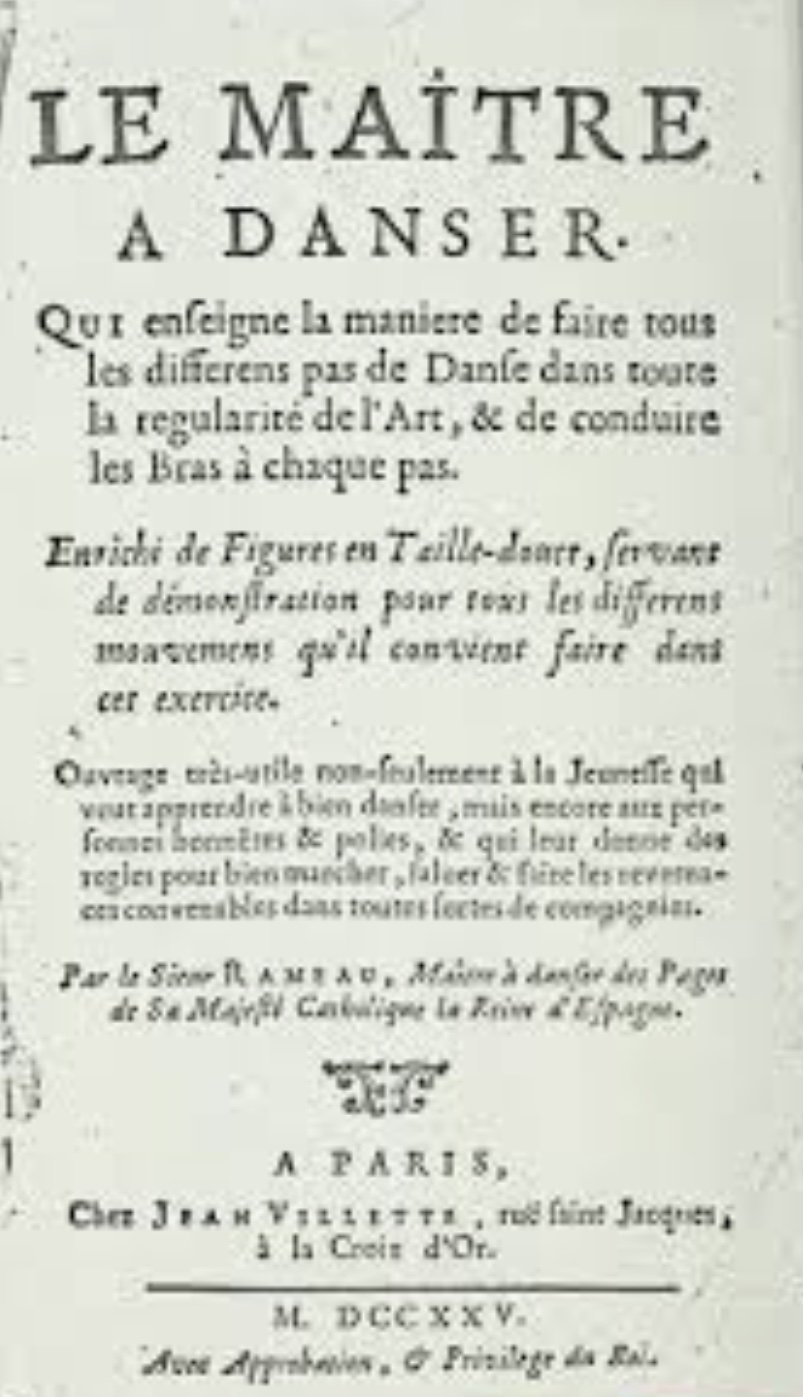

Goff 43. The notated ballroom dances routinely record third positions <5>; and I think that these often appear in the stage dances too. Going back to Rameau and Le Maître à danser <2>, he says:

“This position is for enclosed and other steps: it is called emboîture, and not unreasonably, for this position is only perfect when the legs are well extended and near each other. It is done with the legs and feet close together, so that no light can be seen between them, and they join like the sides of a box.” (Rameau, translated by C. W. Beaumont, p. 9)

Rameau added “This position is one most necessary to good dancing”. I have used Beaumont’s translation, which was published by him in 1931 as The Dancing Master, instead of the contemporary translation by John Essex, as the latter unhelpfully paraphrases Rameau here and elsewhere. Third position <5> is not an easier substitute for fifth <10>, but a fundamental part of the variety and sophistication within baroque dance.

Macaulay 44. Were the feet much closer together in baroque second and fourth positions than in modern ballet? What distances were prescribed?

Goff 44. In Le Maître à danser, Rameau specifies that in second position there should be the length of a foot between the two feet. He is not specific with fourth position <6, 7>, referring only to “that correct distance which should be observed whether in walking or dancing” (Rameau, translated by Beaumont, p. 9), although that too suggests not more than a foot’s length apart.

In practice, too, I think that the feet in open positions were closer together than in modern ballet, in keeping with the greater emphasis on aplomb within baroque dance even when travelling.

Macaulay 45. Today, there are two fourth positions - open/ouvert, with each heel touching the same invisible vertical line, and closed/croisé, with one foot turned-out directly in front of the other (toe before heel, heel before toe). Were both fourth positions used in the baroque era?

Goff 45. According to Rameau, “the feet are placed one in front of the other, and are in a straight line without being crossed, especially when dancing” (Rameau, translated by Beaumont, p. 12), but this is not clear from the accompanying illustrations provided by Rameau himself and by Essex <6, 7, 8, 9>. (Essex initially had illustrations emulating those of Rameau, but later commissioned new plates by the artist George Bickham the younger). I’ve provided some pictures – Rameau first <6, 7>, Essex’s first illustration <8> and Bickham’s later version side-by-side below <9>. (The Bickham is taken from Beaumont’s translation of Le Maître à danser). I think they will give you an idea of the difficulties in interpreting and working with this material!

The notated dances tend to show fourth opposite third for steps travelling forwards. In my own exercise for demi-coupé (inherited from past teachers and refined on my own), I use fourth opposite third for the step forward which precedes the Equilibrium (first position balancing on the ball of one foot). This helps to keep the dancer moving in a straight line, whereas a step from first in plié straight forward encourages the dancer to move from side to side as they travel.

Macaulay 46. In the modern era of maximum turnout (each foot at 90 degree positions off the centre line), fifth has become the most vital position of all in ballet, both a criterion for academic pedants and an article of faith for choreographic classicists. For Balanchine and his disciples, fifth position was and is the key that unlocks space. What does it seem to you to have been in the baroque era?

Goff 46. Could you say more about Balanchine’s dictum that fifth position “is the key that unlocks space”? I ask because Rameau prescribes it “for crossed steps and for moving sideways to the right or left”, adding that “It is inseparable from the second” (Rameau, translated by Beaumont, p. 13). He also says, “to perform it well, the heel of the foot that crosses must not pass beyond the toe of the rear foot” – suggesting that the fifth position <10> was usually well-crossed. I don’t think that in baroque dance fifth position had the same talismanic value that it now has in ballet.

Macaulay 47. As I understand it, the tight fifth position in Balanchine technique is the key to the space because the legs address space horizontally but may also move ahead or backward, while the space between them is shut; and the flat foot may also propel them upward. Balanchine begins his Concerto Barocco (1941) with eight women in fifth position <11>: it’s shown as an article of faith - everything emanates from there. And the first thing those women do in that ballet is relevé: upward before stepping sideways into second.

The dancer and historian Belinda Quirey (1912-1996) used to say that another vital point of baroque style was that the body’s weight was over the front of the foot. If so, that’s another connection with Balanchine and some - not all - other schools of modern ballet. For Belinda, who had a remarkably kinaesthetic response to pictorial and sculptural depictions of the body, this placing of the weight was what the statues and pictures told her. Do you agree that this placing of weight over the front of the foot is integral to baroque dance style?

Goff 47. In baroque dance as I practise it, the weight is generally over the ball of the foot. Is that what Belinda Quirey meant by the front of the foot? I don’t think that the weight is as far forward as it is in ballet, because baroque dance has less forward momentum.

Macaulay 48. Belinda also spoke about the particular elasticity of the instep in baroque dance and its marvellous use of the knee. Would you concur? If so, can you enlarge?

Goff 48. This question relates closely to the preceding one. Yes, I agree about the elasticity of the instep, which also needs to be strong, because it is used to control the rise and fall which is so characteristic of baroque dance and needs to be smooth and not jerky. Although many of the steps are done on quarter- or half-point, I think that a three-quarter point may have been used to achieve certain balances – for example where the working leg describes an ouverture de jambe – which are not held for long.

I don’t know what Belinda Quirey’s thoughts were on the use of the knee, but I was taught and continue to use a slightly relaxed knee for most steps. I don’t think that baroque dance ever requires much in the way of fully straightened and extended knees, because of the use of quarter- and half-point and the lack of lengthy adagio sequences requiring sustained balances. I am aware that some researchers now have very different ideas and I do believe that, as the 18th century progressed, technique changed. I am focussing on the period up to the 1720s and 1730s.

Macaulay 49. A second transformative reform came in 1672, when professionals began to take noble roles in ballet.

One old mistake used to be that the idea that there had never been professionals in Western dance before. Actually, professional dancers had been around from the Roman Empire. But now they were trained to reproduce the noble roles, to give the public performances of roles often originated at court by those close to Louis XIV. To this day, dancers are encouraged to carry themselves like princes and princesses, even in democracies that got rid of their royalty centuries ago.

But am I right about these professionals? Or had they been used in the ballet de cour before 1672?

Goff 49. Your reference to 1672 links the emergence of professional dancers to the establishment of the Académie Royale de Musique (the Paris Opéra) in that year. Professional dancers had certainly appeared in the ballet de cour before then, although your concern is noble roles and their influence on the comportment of succeeding generations of ballet dancers. The surviving livrets for the ballets de cour given between 1651 (the Ballet de Cassandre) and 1669 (the Ballet de Flore) – the period during which Louis XIV himself danced in these productions – show around a dozen male professional dancers and some half a dozen female professional dancers performing in them. However, it is not easy to define their dancing roles. The earlier ballets seem to carry on the tradition of burlesque and even grotesque themes and characters from the reign of Louis XIII. Over time, both became more serious.

A quick survey of dancers and their roles over the period of Louis XIV’s appearances as a dancer, suggests that male professional dancers were more likely to dance comic and grotesque roles (which even the King himself took on occasion). Several of the professionals danced what might be called ‘noble’ roles in a number of ballets. Chief among them was Pierre Beauchamp, who often danced alongside his pupil Louis XIV. Beauchamp danced as Polexandre in the Ballet Royal d’Alcidiane (1655) and as La Renommée (with Louis XIV as Regnaut) in the Ballet des Amours déguisés (1664). In the Ballet des Muses (1666) he danced as Alexandre (Alexander the Great) and, as Theagene, appeared alongside the King as Cyrus the Great and the Marquis de Villeroy as Polexandre. In the Ballet de Flore (1669), Louis XIV appeared as Le Soleil in the first Entrée with the four elements – Monsieur le Grand as L’Air, the Marquis de Villeroy as Le Feu, the Marquis de Rassent as La Terre and Beauchamp as L’Eau. Beauchamp was certainly exceptional in the number of such roles that he performed, but he was not the only professional who did so.

I should also mention the female professional dancers, who often took serious roles. They danced with male noble amateurs but never appeared on stage alongside female members of the nobility.

This is a complex area which needs far more research and analysis. I have one question myself. As ballet developed over the 18th and 19th centuries, what happened to the comic and burlesque elements of performance which were so important at the French court during the 17th century?

Macaulay 50. I’d say that various shades of comic and burlesque dancing were alive in ballet up to the mid or late twentieth century. Think of the less classical guests who come to Aurora’s wedding in The Sleeping Beauty, think of Widow Simone and Alain in Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée. What has always been controversial is how strictly dancers should be categorised into one genre or another - so it’s good to read that Louis XIV himself liked to dance comic and grotesque roles now and then. As you know, a lot of work has been published about all these genres in the Baroque Dance zone of Facebook: I’ve learnt much there from the writings of the Canadian scholar Edmund Fairfax and others.

Can you tell me about the sociology and status of these professional dancers? The professional dancers of the Middle Ages, we’re told, were considered unacceptable by the Christian Church, and had to be buried outside hallowed ground. After 1672, parts of the Paris Opéra were frequented by prostitutes, who did good business; but the female dancers themselves were not unrelated to prostitutes. Louis “le grand Dauphin” and two male friends is said to have abducted three women Opéra dancers for days of debauchery. Marie Sallé’s chastity was considered one of the miracles of the Opéra. Until the early twentieth century, a great many women ballet dancers were available for rent, whether to Grand Dukes or to less posh men. One corps dancer of the eighteenth century is said to have lined her entire chamber with bank notes from ceiling to floor.

If a female dancer was lucky, like our friend Hester Santlow, she made her fortune by way of stage success and rich protectors, then acquired a new respectability by way of marriage and finally retirement. If a dancer was unlucky, like the Marie van Goethem whom Degas immortalised as the Little Dancer aged Fourteen, she came from a milieu of prostitution and simply vanished, very possibly by way of the brothels.

Would you add or subtract anything to and/or from this view of the dancer’s sociological and/or sexual status, at least in your chosen period of 1650-1750?

Goff 50. I would like to be able to tease out this question more fully, but I will have to concentrate on London as I know more about it. While it is true that London’s theatres – Drury Lane and Covent Garden in particular – were situated in an area notorious for its low life, it is worth remembering that only a few streets away (in Leicester Fields and Piccadilly, for example) were the houses of nobility and even royalty. Such a juxtaposition cut both ways of course. Another feature that has emerged from my research is the importance of family in London’s theatres. There were acting families with dancers among them, who married into other acting families and had children who became actors or dancers themselves. They have attracted little attention because their lives lacked notoriety (even though a number of them were leading performers) – they form a silent background to the noisy antics of a few of their stage contemporaries.

Macaulay 51. Some of the baroque style we see in various revivals and reconstructions seems to me a particularly French style. Those flourishes of the hands and wrists , perhaps derived from reading Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître à danser, seems perfect for the harmonic tensions and musical phrase-endings by Lully, Campra, and Jean-Philippe Rameau. I’m not sure if they’d work so well to music by Bach or Handel. Do you have any ideas - is there any evidence - of how baroque dance style varied from country to country and from music to music?

Goff 51. May I just comment on the composers you mention? Lully, Campra and Rameau wrote dance music for their operas and that music was used for dancing on the London stage, even though the operas were never given there during the 18th century. Handel included music for dances in his Italian operas for London, but worked with French or French-trained dancers – not just Marie Sallé but also the English dancer Leach Glover. Bach never wrote “dance music”, although he drew on dance types endlessly. I find it disappointing that teachers of baroque dance turn to Bach so readily, rather than exploring and exploiting the wealth of 18th-century music which was actually written for dancing and would teach us so much more about that dancing.

I am sure that baroque dance style did differ from country to country although, as yet, little clear evidence of this has been uncovered. Differences can be guessed from the choreographic styles in England and France in the early 1700s. For me, it stands to reason that musical changes between Lully and Rameau both responded to and led changes in dance style and technique. Sadly, we cannot chart these directly because we have almost no stage dances recorded in notation after the 1720s. What we can see, and again I am looking at the repertoire on the London stage, is the appearance of new dance types, for example the Tambourin which reached Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1730-1731 danced by Marie Sallé as a solo and quickly became a staple of the entr’acte repertoire.

Macaulay 52. I always feel we know far too little about dancing in Italy in centuries past. Catherine de Medici really imported ballet to France from Italy in the late sixteenth century, and great Italian dancers - Barbarina Campanini, Gaetano Vestris, Fanny Cerrito, Carlotta Grisi, Carolina Rosati, Amalia Ferraris, Giuseppina Bozzachi, Virginia Zucchi, Enrico Cecchetti, Pierina Legnani, Carlotta Brianza, and others - kept galvanising the ballet of Northern Europe during the eighteen and nineteenth centuries, not to mentioning the writing and teaching of Gennaro Magri, Carlo Blasis, and Cecchetti. The best Italians brought new technical brilliance and/or new dramatic intensity. But what sense do you have of Italian style during the period 1650-1750?

Goff 52. I am currently writing a short piece about the ballerina Barbara Campanini <12>, La Barbarina (1721-1799), whose appearances in London and dance partnership with George Desnoyer are of interest to me. She wasn’t the first Italian dancer (as opposed to commedia dell’arte player/dancer) to visit England but she was followed by others who certainly influenced the entr’acte dance repertoire in London’s theatres. There are glimpses of their dancing and some of their other stage skills (which sometimes extended to out-and-out acrobatics). In London, and doubtless elsewhere in Europe, the Italians were known for both expressive and highly virtuosic dancing.

Macaulay 53. And what evidence do we have for baroque dancing in Germany, Austria, Spain, and other countries? I mean evidence for how people danced in those countries, onstage and/or in the ballrooms.

Goff 53. So far as I am aware, there is quite a lot of research going on around Europe which is focussed on both stage and ballroom dancing during the 17th and 18th centuries. What I have seen and read confirms both the predominance of French style and technique and the importance of local variations. Although I can’t provide much in the way of detailed evidence, I think that the work is based on notated dances, dance manuals and eye-witness accounts from those countries as well as investigation of the dance repertoire in local theatres and at regional courts.

Macaulay 54. Halfway through your period, around 1699, the two foremost French dancers of the day appeared in London: Claude Ballon and Marie-Thérèse du Subligny. Doubtless they were lured by money and/or prestige, but what do we know of the fare they offered? Was it the same they danced in Paris - or did they bring anything the Parisians might not have expected?

Goff 54. We don’t know much at all about what Ballon and Mlle Subligny danced in London.

Ballon <13, 14> apparently danced at the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre during April 1699. A contemporary report says he was paid 500 guineas for his five-week visit (approximately £55,000 today). He is recorded as performing an “Entertainment of Dancing” on 10 April, but no specific dances are mentioned. We know that during April he and Anthony L’Abbé danced together before William III at Kensington Palace – as I have already mentioned L’Abbé created the “Loure or Faune” duet that they performed. They must surely have given other duets and solos, but we don’t know what these were. It is reasonable to surmise that Ballon brought some of his repertoire from the Paris Opéra and, because it was apparently the custom for the leading male dancers there to create their own solos, he presumably performed his own choreographies, some of which he could have created specifically for London. At Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Ballon may well have danced with L’Abbé but did he partner any of the local ballerinas? Might he have danced with Mrs Elford, who was later L’Abbé’s preferred female partner? She appeared with the young Hester Santlow in L’Abbé’s choreography to the passacaille from Lully’s Armide.

Marie-Thérèse de Subligny <15> visited London briefly, perhaps between late January and early April 1702. Although we have no record of her performances, we do know two of the dances she performed at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. The 1704 Recueil of Guillaume-Louis Pecour’s choreographies for the stage includes the “Gigue pour une femme dancée par Mlle Subligny en Angleterre” to music from Theobaldo di Gatti’s 1701 opera Scylla. The Nouveau Receuil of Pecour’s dances, published around 1713, has the solo “Passacaille pour une femme dancée par Mlle Subligny en Angleterre de lopera darmide”. With these two dances Mlle Subligny was bringing French choreographies to London, although we don’t really know whether they were specially created for her visit (Lully’s Armide was revived at the Paris Opéra in 1697 and then not until 1703). We have no record of what she was paid for her visit but the indications are that it was an extravagant sum.

I think it unlikely that either Ballon or Subligny went beyond the expectations of their Paris audiences – the point of their respective visits to London was surely to showcase the best of French stage dancing.

Macaulay 55. Anthony L’Abbé danced a duet with Ballon for William III in 1699; he was a leading London dancing master here for many years. Was he, L’Abbé, both French and French-trained?

Goff 55. Anthony L’Abbé was both French and French-trained. He was born around 1667 and made his debut at the Paris Opéra in 1688, subsequently dancing in Lully’s Cadmus et Hermione (in 1690) and Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (in 1691), among other works. He was brought to London by the actor-manager Thomas Betterton in 1698 and seems to have settled in London by 1700. It is interesting that L’Abbé was the brother-in-law of Mr Isaac, dancing master to Queen Anne. L’Abbé himself was appointed royal dancing master on the accession of George I. From 1700 until he left England in 1737 or 1738, L’Abbé first danced and then choreographed and taught dancing. The evidence of his notated dances reveals his French background but also shows the English influences on his dances for both ballroom and stage.

Macaulay 56. Can we tell what impact Subligny and Ballon made in England? Is it too much to think they ignited the new age of dance excellence that followed at Drury Lane in 1706-1733? Was it principally to them that John Weaver referred, do you think, when he objected to the inexpressive brilliance of French dancing?

Goff 56. I am inclined to suppose that the impact of these two French star dancers was both positive and negative. They were certainly not the first and not the only French dancers to visit London – other dancers from Paris came earlier, stayed longer and danced alongside English dancers (one of them was Hester Santlow’s teacher René Cherrier), but Ballon and Mlle Subligny, as well as L’Abbé, were acknowledged celebrities. John Weaver actually names Ballon in his 1712 An Essay towards an History of Dancing:

“They have observed in Ballon (the best we have seen on our Stage) that he pretended to nothing more than a graceful Motion, with strong and nimble Risings, and the casting his Body into several (perhaps) agreeable Postures: But for expressing any Thing in Nature but modulated Motion, it was never in his Head: The Imitation of the Manners and Passions of Mankind he never knew any thing of, nor ever therefore pretended to shew us.” (p. 137)

Weaver writes as if he was reporting what others had seen, but he may himself have attended Ballon’s performances at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. By 1712, Weaver was formulating his own ideas on expressive dancing and it was only in 1714 that Ballon performed a scene in dance and gesture with Mlle Prévost at Sceaux.

There is no direct evidence of Ballon’s influence on London’s professional dancers, but Mlle Subligny’s impact can be seen in both comic and serious attempts to emulate her dancing. There was the ‘Dance in Imitation of Mlle D’Subligny’ given several times by the Devonshire Girl in 1703 and 1704, as well as L’Abbé’s female duet to the passacaille from Armide (surely a response to Subligny’s solo given in London). I think that Ballon and Subligny contributed to, but were not principally responsible for, the enhanced standards of dancing at Drury Lane in the following decades. The dates you quote accord with the career of Hester Santlow, who I believe was the greatest English professional dancer of the period – and French trained.

Macaulay 57. London’s dancing perhaps both suffered and profited from not having an academy and an established academic tradition, which the French did have. In the last century, I gave a lecture for you at the British Museum in which I hypothesised that Paris was where the rules of dance were made, London was where the French dancers broke those rules when they chose. I can back up my hypothesis, but you’ve given a hundred times more attention to all this than I. How do you compare the dance scenes of London and Paris in 1650-1750?

Goff 57. Dancing changed a great deal in both Paris and London between 1650 and 1750, but I think that you are right in your hypothesis – although we may well differ in our interpretations of what was happening in those two great centres of theatrical dance. Paris was certainly where the codification of dance technique took place, first at the French court (Louis XIV instituted the Académie Royale de Danse in 1661, which lasted until 1789) and then at the Paris Opéra. There were no parallel institutions in London and no state subsidy for any of the theatres. Drury Lane, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Covent Garden and the Queen’s/King’s Theatre (the opera house) were all commercial operations. So far as dance was concerned, they were answerable only to their audiences for whom dancing in entr’actes and afterpieces was a necessity. Such dancing was characterised by opportunistic borrowing and entrepreneurial creativity, which was probably what attracted dancers from the continent (as well as the money). Where I may differ from you is in the significance I attach to stage dancing in Paris beyond the Opéra. The Paris fairs were sites of exchange between dancers from Paris and London. Thanks to researchers in France and elsewhere, I am only now learning about the dancing at the Comédie Française as well as the Comédie Italienne – I suspect that rules were broken in both and that they contributed to the breaking of rules in London. There was a vibrant dance scene in Paris, but it did not only reside within the walls of the Académie Royale de Musique. London’s world of stage dancing is still awaiting proper exploration and analysis of its eclectic variety.

Macaulay 58. The ballerina Marie-Anne Cupis de Camargo never danced in London, but today a famous painting of her dancing by Nicolas Lancret hangs at the Wallace Collection <16>. Can I ask you to speak of the dance information in this painting?

Two things strike me in particular . One: the outstretched, generous, and radiant openness of her pose, which beautifully demonstrates the amplitude and multi-directionality of ballet even in the 1730s. Two: her supporting leg seems to be in both relevé and plié, a combination we seldom see in any sustained pose in ballet today.

Some observers have made much of the male musicians acting as voyeurs on the ground: disturbing evidence of what we now call the male gaze. Considering that the 1730s were an era when glimpses of women’s legs were rarer than they are today, I’m not taken aback; and any voyeurism is muted compared to that shown in another French eighteenth-century painting in the Wallace Collection, Fragonard’s The Swing (1767). I love the fantasy Lancret creates that Camargo is dancing in a Watteau fête galante; and I adore the very Watteau sensuousness of the fabric of her dress. Your own thoughts?

Goff 58. I’ve often wondered whether La Camargo <see also 17, 18> was performing a contretemps de côté, a step which begins in a demi-plié in second position before a rélevé sauté onto one leg with the other extended to the side taking the arms into the position we see in Lancret’s scene. Despite myself, I do love this little painting and I always want to copy her pose when I am in front of it. I admire the lift in her torso, which seems to be only lightly corseted allowing her freedom in épaulement (the same lift can be seen in Lancret’s more sedate portrait of Sallé). Up close, it is possible to see how high the red heels of her shoes are – she is certainly not dancing in ballet slippers and I wager that she could have performed an entrechat-six even in those heels.

You do know, of course, that Camargo’s bent supporting leg was the subject of a critical review of the portrait at the time. I wonder if women’s legs were so rare a sight in the 1730s as we think - there are a handful of accounts of dancers in London that suggest that audiences would get far more than a glimpse of ankle, or even calf, as they performed. Pastoral scenes with shepherds and shepherdesses were the stuff of dance fantasies in both London and Paris – in London there was even a dance scene based on Watteau’s painting L’Embarquement pour Cythère <19>!

@Moira Goff 2022 @Alastair Macaulay 2022

1.This painting depicts an actual ballet de cour at Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna, on January 24, 1765, with the juvenile archdukes Ferdinand and Maximilian and archduchess Marie-Antoinette (María Antonia), to music by Gluck, for their mother the empress Maria Theresa. It was commissioned in 1778 by Marie Antoinette, when she was queen of France, to hang in the lambris of the Petit Trianon dining room.

2: Pierre Rameau, Le Maître à danser, 1725.

3: First position of the feet: Pierre Rameau, Le Maître à danser, 1725

4: Second position: Pierre Rameau, Le Maître à Danser, 1725.

5: Third position: Pierre Rameau, Le Maître à danser, 1725

.

6: Fourth position: Pierre Rameau, Le Maître à danser, 1725

7: Fourth position: Pierre Rameau, Le Maître à danser, 1725.

8: Fourth position: John Essex, The Dancing Master (a translation of Rameau), 1731.

9: Fourth position: John Essex, The Dancing Master, 1731.

10: Fifth position: Pierre Rameau, Le Maître à danser, 1725.

11: The opening image of George Balanchine‘s Concerto Barocco (1942): eight women in modern fifth position.

12: Barbara Campanini (1721-1799), the Italian ballerina often known as “La Barbarina”. Her career took her to London, Paris, and Berlin.

13: The dancer and dancing master Claude Ballon (1671-1744)

14: The dancer and dancing master Claude Ballon (1671-1744)

15: The ballerina Marie-Thérèse Perdou de Subligny (1666-1735).

16: Marie-Anne Cupis de Camargo (1710-1770), by Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743). Wallace Collection, London. Lancret seems to have painted Camargo at least three times; there are other similar paintings that may have been copies “after Lancret”.

17: Marie-Anne Cupis de Camargo (1710-1770) and partner, c.1730, by Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743). National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C..

18: Marie-Anne Cupis de Camargo (1710-1770), c.1730, by Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743). Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

19: L’Embarquement pour Cythère (1717), by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721). Louvre Museum, Paris.