“Raymonda” and Ballet Herstory: historians Doug Fullington and Sergey Konaev on Lydia Pashkova, Ivan Vzevolozhsky, Marius Petipa, and the Russian Imperial Theatres. A “Raymonda” questionnaire.

On Tuesday 18 January, English National Ballet presented a new production of Marius Petipa’s Raymonda (1898) by Tamara Rojo: this is a co-production with Finnish National Opera and Ballet. Petipa’s ballet, best known from various twentieth-century productions by leading Russian dance figures, tends to treat the Islamic Saracens as bad, the Christian crusaders as good. Rojo’s production - by transferring the action from the mediaeval era to the nineteenth century and casting Raymonda as Florence Nightingale (the Lady of the Lamp, as now seen in Raymonda advertisements around London) - has changed the ballet’s cultural emphasis.

But Rojo also took the initiative of involving the dance historian Doug Fullington on using dance information from the original Maryinsky production. Fullington and I have been friends and correspondents since 2007. Here he answers one series of questions from me about his understanding of Raymonda. We began this correspondence before the premiere of Rojo’s production, which he was unable to attend.

He has now been joined in this questionnaire by Sergey Konaev. Konaev, a historian of ballet and other performing arts, worked for years in the archives of the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow. We became acquainted in 2015 after he published his discovery of long lost features of the original 1877 Moscow production of Swan Lake; we first met at a Harvard Theatre Museum conference on Marius Petipa in 2018. He is preparing a book about the Russian nineteenth-century productions of Swan Lake. The two men have met on Konaev’s visits to the United States and admire each other’s work.

Fullington and Konaev are both busy men. I thank them for spending so much time on this project. All three of us intend to continue with the questionnaire when time allows. AM.

Macaulay 1. Doug, Sergey, I hope that by conversing about Raymonda , we’ll all deepen our love for it.. But let’s begin by saying what’s special about this ballet. Probably first of all the Glazunov score: I love its wealth of melody, its range of colour, its rhythmic panache. In some moods, I complain of a few passages, but seldom and few.

Fullington 1. Glazunov’s score for Raymonda is the biggest draw for me. I love its tunefulness, recurring motifs, and orchestration. The complete recording on Naxos is my favorite.

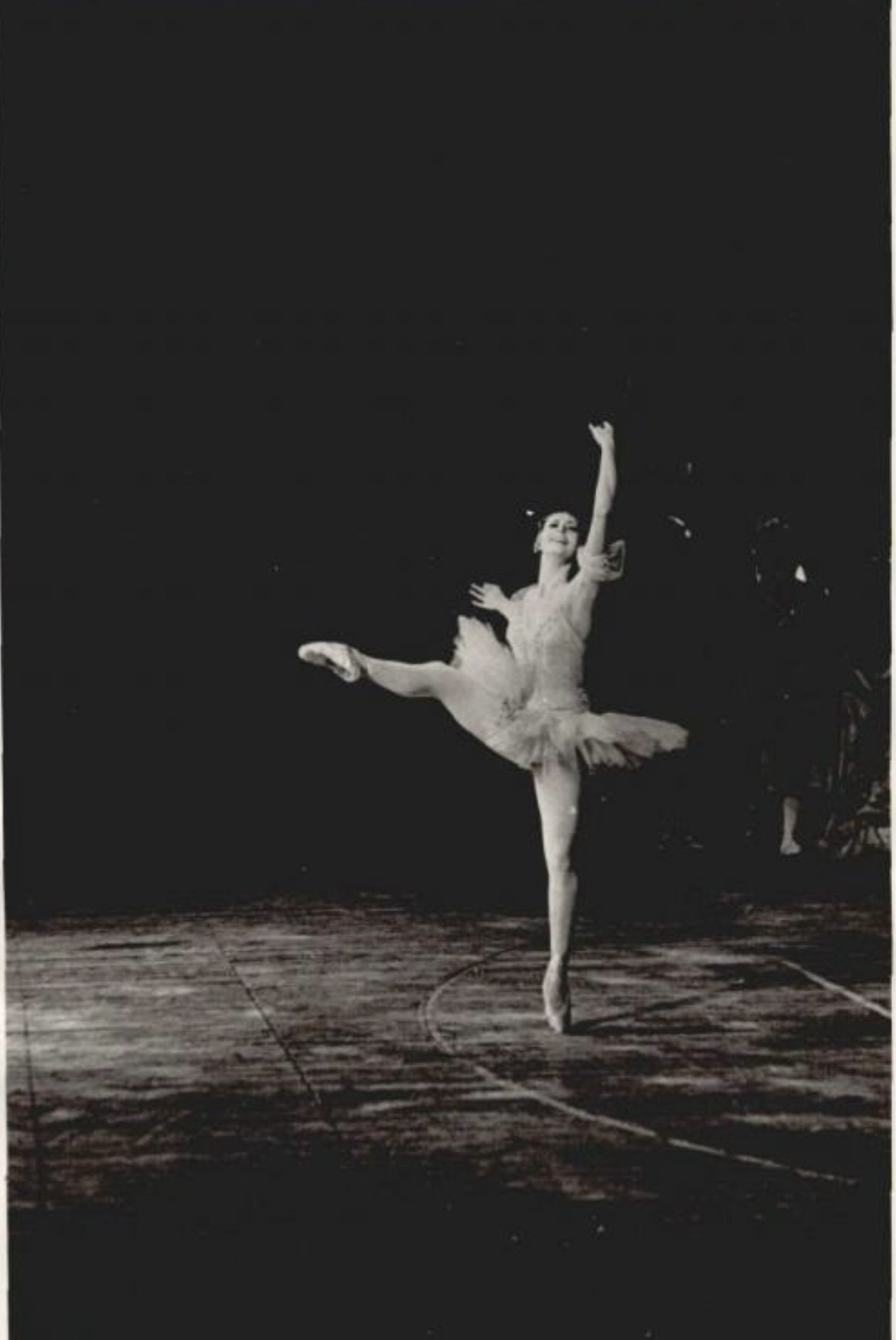

Konaev 1. In Russia, Raymonda is always in repertory, so I’ve loved to study it and read around it. For me, it is the most melancholic of all classic ballets, and it’s also a unique marriage of choreography and music: in particular in the last act, the Grand Pas Classique Hongrois, Czardas, Entrée, variation for four cavaliers, Raymonda’s variation. So my favorites are not recordings, but films and footages: a colour film featuring Leonid Lavrovsky’s staging for Bolshoi mixing Petipa and Gorsky, black and white footages from this staging with Maya Plisetskaya (1950s-1960s), the excepts from Kirov’s 1948 production by Konstantin Sergeev danced by Natalia Dudinskaya and Sergeev himself, the entire video of this production with Irina Kolpakova (1980).

Macaulay 2. And then it shows us the master-choreographer Petipa in something like top form, working with three leading artists he greatly admired - Pierina Legnani, Sergei Legat, Pavel Gerdt - and with a company he has brought to a glorious peak. There are several ballets in which this Petipa work is individually special: what are the particular aspects that most fascinate you with Raymonda?

Fullington 2. In large part, Raymonda is a series of dance suites in varying styles. Petipa included academic dance, character/national dance, and his take on historic French dances. Raymonda provides the opportunity to see Petipa working in all these styles in his eightieth year.

Konaev 2. Raymonda is the last of the large-scale ballets that have become “must-have classics”, designed and realized under Ivan Vsevolozhsky as a director of the Imperial Theatres. It’s a result of the entire production culture of Imperial Theatres - all these clouds, mystical appearances and disappearances; it reflects the very air of the 1890s in imperial capital St. Petersburg, the Francophonie advocated by its director, the staggering beauty of the palaces, the irrational beliefs, the séances chiming with the White Lady (La Dame Blanche) as a key character of this scenario. And it’s a peak of Petipa’s method of creating a show, his skills as a theatre director, not only a choreographer.

Macaulay 3. Remind me how and when each of you became interested in Stepanov notation.

Fullington 3. I was given Roland John Wiley’s book Tchaikovsky’s Ballets by my parents in 1985. I read about Stepanov notation and, as a musician interested in ballet, was fascinated to find that it was a choreographic notation system based on Western musical notation. I immediately wanted to learn it.

Konaev 3. As a researcher throughout the 2000s, I’ve been interested in the various ways of documenting theatre production and dances. I started from descriptions in a simple written form found in the archive of Olga Preobrazhenskaya at the Bakhrushin Theatre Museum in Moscow, and eventually came to read and understand Stepanov’s notation because it was a key point of the not at all harmless debates and intrigues that unfolded around the Petipa reconstructions by Sergey Vikharev and Pavel Gershenzon at the Mariinsky, starting with the 1999 production of The Sleeping Beauty.

Macaulay 4. Doug, this means you were already acquainted with the area when Sergei Vikharev staged The Sleeping Beauty for the Kirov/Maryinsky in 1999. When did you begin to work with dancers on nineteenth-century choreography?

Fullington 4. In 1999, the staff of the Harvard Theatre Collection asked if I would work with Pierre Lacotte on his production of The Pharaoh’s Daughter, which he was creating for the Bolshoi Ballet. We did this remotely. I worked with some generous dancer friends at Pacific Northwest Ballet in Seattle to videotape the excerpts that Pierre sent me (choreographic notations and corresponding musical passages from the Harvard violin répétiteur). He ultimately used little of what we prepared, but the experience was good for me. I was very green.

Konaev 4. In the context of Russian ballet, it was Vikharev and Gershenzon who deliberately gave to critics and researchers an instrument to verify their reconstructions at the Mariinsky. They introduced notations as a pivotal part of historically informed approach when reconstructing or reviving classics, they proposed documents as alternative to folklore method, to modernist amendments and unverified legends on authorship still common for Soviet and Russian ballet. Paradoxically, Leningrad-St.Petersburg ballet tradition has attributed some artists (it can be second soloists, for example) with outstanding qualities of memory, but this was verified only after comparing some privately filmed videos featuring some of Agrippina Vaganova’s former pupils of unknown or uncommon variations with Sergeev’s notations.

Unlike Doug, I never worked with dancers directly. When Yuri Burlaka invited me as his assistant on archive research for the Bolshoi’s stagings of the Grand Pas from Paquita (2008) and the complete Esmeralda (2009), he assumed that I would decipher the notation for a choreographer and then he in turn would communicate it to the artists. But at that very point I discovered software LifeForms and its variant DanceForms for creating dances, which once attracted the attention of Merce Cunningham (who indeed helped to develop DanceForms). It was a special pleasure to reconstruct dances as animations, especially using visual dictionaries of classical movements in various schools (Royal Ballet, Vaganova, Cecchetti) as created by Rhonda Ryman, a former ballerina and an expert in Benesh and Laban, based in Canada, who developed DanceForms further. Two of my animated reconstructions based on Alexander Gorsky’s notation scores - one exercise and his male variation from Swan Lake - are available on YouTube, but I keep dozens of them on my laptop.

Macaulay 5. Doug, you’re also a practising musician. How do you feel this colours your work on these old ballets?

Fullington 5. I’m as interested in the music of a ballet as I am in the steps, and I believe in using original orchestration whenever possible. Reading music is crucial to working with Stepanov notation. Of course, knowing which music was used for a particular dance — and whether cuts or addition were made to it — is essential when reviving a dance.

Konaev 5. I’m in no way a practising musician - but, after studying lots of notations which kept the music score and struggling with countless others that didn’t, I must confess that the serious problem is the evolution since the late nineteenth century of our notions on what is musical and what is not. In Petipa’s time, it was okay to repeat the same combination, let’s say, three times, ignoring the fact that after the second one the melody or key changed. That was a point of Fedor Lopukhov’s criticism in the 1920s when he formulated his theory of musicality, analyzing Petipa’s masterpieces and amending his productions at the former Mariinsky. British ballet faced it too in the 1930s when Ninette de Valois invited Nicholas Sergueyev – she and Constant Lambert fought these numerous, weird, little cuts – one or two bar here and there (for example, in Sleeping Beauty) Sergueyev meticulously tried to reproduce. But Sergueyev didn’t invent them - Petipa and even Ivanov did.

Macaulay 6. That’s so interesting, Sergey. I’ve always suspected that Petipa (1818-1910) must have had ideas of ballet music and musicality decades behind those developed by Tchaikovsky (1840-1893). If you’ve spent most of your career working closely happily and successful with Cesare Pugni and Ludwig Minkus, you’re scarcely equipped - especially in your seventies - for the subtle and layered instructions of Tchaikovsky.

Doug, you mentioned your preference for using the original orchestrations for ballet scores. Have there been any significant changes to that of Raymonda? Why do you emphasise your preference for the Naxos recording of the score?

Fullington 6. Not that I’m aware of. Because the orchestral score of Raymonda was published in 1898, it has been available for use all along. The Naxos recording presents Raymonda as published, that is, with numbers that were omitted from the stage performance (two, maybe three, variations) and without numbers that were added (a variation and the mazurka).

Macaulay 7. I’ve read that Petipa complained of Glazunov’s music. Any idea why? As you know, I’ve very limited time for the music of Petipa’s two foremost composers, Cesare Pugni and Ludwig Minkus. But if they’re what Petipa was used to, what problems might Glazunov’s score have given him? I’m inclined to guess that he would have been fine with its dance passages, but that staging its mime and other non-dance sequences might be uphill work. Your thoughts?

Fullington 7. Glazunov was reluctant to make Petipa’s requested revisions to the score. He also published the orchestral score and piano reduction before the performance version (representing Petipa’s ultimate intentions) was finalized.

Macaulay 8. Doug, you and I have lived through decades in which our perception of the historical tradition of the old ballets has changed. When I came to ballet in London in the 1970s, it was generally understood that, thanks mainly to Nicholas Sergueyev‘s work in the 1930s, the Royal Ballet was the world’s foremost exponent of tradition in Giselle, Coppélia, The Sleeping Beauty, and Swan Lake.

Then Roland John Wiley’s book Tchaikovsky’s Ballets (1985, as you said) made us all aware of further details in which the Royal versions could be more authentic. In that decade, the Royal Ballet’s Nutcracker (Peter Wright, 1984) and its 1987 Swan Lake (Anthony Dowell) both purported to have used material from the Stepanov notation for those ballets. I think we can now see that the incorporation of any Stepanov material in those productions was merely superficial - a pity in view of the Royal’s historical status. That’s not your business here - you watch the Royal far less than I do - but, at the time, it did help to set the scene for Vikharev’s work and then your own.

In the twenty-first century, Yuri Burlaka and Alexei Ratmansky have joined the club of Stepanov-literate stagers. In a small way, so have such scholars as Juan Bockamp. Important historically informed, Stepanov-based stagings have now occurred in St Petersburg, Moscow, Milan, Zürich, Berlin, Munich, New York, and Seattle, with you and others involved. Much progress has yet to be made, but you must feel less isolated and eccentric than I guess you did, yes?

Fullington 8. Yes, though I remain something of an outsider, because I wasn’t trained as a dancer. I certainly follow what other dance-revivers are doing and note the level of engagement with the notated material that their stagings represent.

Konaev 8. I appreciate the practice of explanations given in programs by choreographers: what sources were used, what pieces were reconstructed and what was composed anew. In this respect, the trend-setter was the Bolshoi Publishing Department, which included a special table in the program of Alexei Ratmansky’s and Yuri Burlaka’s Le Corsaire (2007). In the program of Ratmansky’s Giselle (2019) I edited, this table was extremely detailed. It’s very encouraging to see that the status of a research and researchers increased for choreographers, directors and theatre decision-makers since 1990s and that revealing and studying documents became a routine (and paid) part of the creative process.

But, after all these years and battles, there is still only one choreographer of the top level who, when dealing with reconstructions, has never told me that notations are not what he expected them to be or that they do not help: that’s Alexei Ratmansky.

Macaulay 9. Doug, your c.v. reminds me that your historical stagings include dances for The Pharaoh's Daughter for the Bolshoi Ballet (2000); Le Jardin animé from Le Corsaire for Pacific Northwest Ballet School (2004); Le Corsaire for Bayerisches Staatsballett (2007); Giselle with Marian Smith and Peter Boal for Pacific Northwest Ballet (2011); Paquita with Alexei Ratmansky and Marian Smith for Bayerisches Staatsballett (2014); and a one-act version of Le Corsaire for Pacific Northwest Ballet School (2016).

Do you describe this work as “reconstruction”? If not, what?

Fullington 9. I used to use the term “reconstruction” for my work with Stepanov notation. The term was used frequently in the early music community, with which I used to be more involved. When I would assemble chant and polyphony to recreate medieval- and renaissance-era liturgies for my choir to perform, we’d refer to the work as a concert reconstruction.

But the term “reconstruction” has become a fraught one in ballet. This stems in part from the various ways in which stagers and choreographers have utilised the Stepanov notations (some stating they have consulted the notations but with no evidence of it shown in their work, some employing only elements such as floor plans, and others endeavouring to be as faithful to the notation as possible). This disparity of use has led to the notion that Stepanov notation can be read and interpreted in various ways, while the truth is that the system is very precise. That said, most of the notations are not fully complete — the majority lack movements for the head, torso, and arms, and some are missing certain enchaînements or have steps written out only in prose. These omissions require the reviver of the dance to make editorial decisions, and therefore the result of one reviver’s work will differ somewhat from another’s. Alexei Ratmansky told me he felt the use of the term “reconstruction” with regard to my work on PNB’s Giselle in 2011 was confusing because the finished product (that is, the choreography as ultimately staged by Peter Boal) did not always accurately represent what was notated — Peter sometimes replaced the notated steps with other steps or changed the timing or the manner in which a step was performed. Alexei made a fair point, and I agreed with him that the term “reconstruction” might better be replaced by “historically informed production.” (I believe Marina Harss suggested this term, also drawn from the early music community, to Alexei.) I’ve since changed my Giselle credit so that I’m listed as a “historical adviser” rather than a reconstructor of choreography. I take extra care these days to be especially clear about my involvement in any production that uses historic notation. I have no interest in misleading viewers or other scholars.

Konaev 9. I agree with Doug that the term “historically informed production” does not mislead, but all ballet productions are more or less historically informed in some relation. There’s a great difference, though, between visionaries who aim to get back the entity of the forgotten masterpiece and the majority of professionals who’re seeking some novelty, a bit of exclusivity, to vary dances in any way – and thus interested only in some excepts of the original. Re-discovered entity disturbs, some stylish novelty pleases. In architecture, the terms “reconstruction” and “restoration” have other definitions and meaning besides “building exactly what was demolished on this very place, from the same materials”. It can be, for example, “restoration of the structure of the old city in the new architectural embodiment”, that includes height limits, skylines, proportions, the nature of landscape.

Macaulay 10. Doug, you aren’t the first modern scholar to tackle Raymonda. Vikharev did so for La Scala, Milan. I remember that you questioned the accuracy of parts of Vikharev’s work on The Sleeping Beauty and La Bayadère for the Kirov/Maryinsky (I certainly did): what did you feel of the job he did on Raymonda?

Fullington 10. Vikharev’s Raymonda, which I saw three times at La Scala in 2011, was a puzzle to me. It looked and sounded great, but more often than not he relied on choreography from Konstantin Sergueyev’s 1948 Kirov version than on the notated material. He also ignored virtually all of the mime included in the notation. The excellent program book, with valuable essays written mostly by Pavel Gershenzon and Sergey Konaev, did not acknowledge or explain the reason for this, so we may never know.

Konaev 10. Not being a member of the creative team for La Scala’s Raymonda, but, having watched the productions of Vikharev and Gershenzon from the very first one and having had occasional talks with both men, I think there are some things worth to be mentioned about their approach. Every production of theirs was a reconstruction of entity, of a complete Petipa-Vsevolozhsky spectacle – rich, overcrowded, with spectacular mis-en-scenes, mixed colours of costumes and choreography as just a part of the show. I’m a big fan of what they were doing, because it wasn’t about ballet only – it was about ballet as a part of a once flourishing visual culture, about pulling the ballet out off the cosy theatre routine back to the domain of art style and provoking discussions to where it belonged at the moment of creation.

Of course, a reconstruction of let’s say the Première exposition des peintres impressionnistes could be a tricky thing in a direct sense – to collect the paintings, to hang them in the historical order. But the real achievement would be to reconstruct the impact this exhibition had on art development and public. Gershenzon once mentioned that only art critics and historians understood completely what was meant and realized in 1999 with their Sleeping Beauty. In the early 2000s, the Mariinsky was a right place for both things – it had all resources to realise Vikharev’s and Gershezon’s ambitions to present Petipa’s and Vsevolozhsky’s designs and there were still many passionate people around theatre ready to make you much harm for questioning the Konstantin Sergueyev productions of classics or its aesthetic values not to mention replacing them.

Raymonda at La Scala was the peak and last production made under these principles. Two productions for Ural Opera Ballet, La Fille Mal Gardée (2015) and Paquita (completed after Vikharev’s tragic death by Slava Samodurov and recently shown by Mezzo) manifest a “what if” approach (what if the Directorate of Imperial Theatres commissioned set-designs of La Fille… to Van Gogh) and find ways to contemporary culture via its practices (self-reflection, self-criticism, self-questioning) and visual forms (installations, mixed technique, captioning).

As for choreography in Raymonda, all the sources were found and used as always. Besides documents employed to reconstruct action and mis-en-scene, Vikharev and Geshenzon used a paper written by Konstantin Sergueyev for some copyright needs, with detailed remarks on authorship of choreography – where’s Petipa (or rather what was considered Petipa when Sergueyev entered the Kirov Ballet) and what he composed himself. Of course there’s a big slippery zone between the 1900s, when the notations were completed, and the 1940s - but formally Vikharev had reasons to rely on Sergueyev’s production. Also, they made at La Scala what seemed impossible – the character dances were performed almost by the standards of the Mariinsky with its live undamaged traditions of character school.

In what related to the classics, Vikharev read notations perfectly, but he was a bit skeptical about efforts to restore the old-style lower angles of raised legs. He would point out that it’s an easy thing for the public to discuss – unlike nuances of ankles’ work - and he saw no reason to reconstruct the old style of dancing (which would have required the re-teaching of mature artists who had been accustomed since childhood to polish and fit the standards of latterday schooling). I asked him once “Don’t you want to introduce those relaxed Italian attitudes for the ballerina as in Shiryaev’s animations?” and he replied, “Why, she’ll fall down and that’ll be the only effect!” It was a half joke told with serious face; but the truth is that he loved to work with dancers and to push their creativity. I guess it’s the primary source of compromises he made in the choreography they danced.

Macaulay 11. Parts of Vikharev’s La Scala Raymonda crop up on YouTube; a DVD recording of the entire production has been issued. How close are its designs to those of 1898?

Fullington 11. Close, I believe, although I haven’t made a direct comparison.

Macaulay 12. Doug, Raymonda is one of five ballets on which you are currently completing a book. Can you tell me a little more of this book?

Fullington 12. Marian Smith and I have co-authored a forthcoming book in which we discuss Giselle, Paquita, Le Corsaire, La Bayadère, and Raymonda using source material — mainly musical scores, the staging manuals of Henri Justamant, and the Stepanov notations. We have limited ourselves to productions staged in Paris, Lyon (where Justamant was ballet master when he created his manuals for three of these ballets), and St. Petersburg. We discuss music, mime, and choreography in detail, and we also identify common features of these and other ballets. Our main point is that source material provides a wealth of vital detail about how these ballets were performed and can contribute to our knowledge and performance of these works today.

Macaulay 13. It’s well known that Tamara Rojo is updating Raymonda to the context of the nineteenth-century multi-national Crimean War and Florence Nightingale, “the Lady of the Lamp”. This may sound odd to ballet conservatives, yet it may prove no more so than Dowell’s transfer of Swan Lake to the nineteenth century while using some historical findings about the 1895 Petipa-Ivanov Maryinsky original. And it’s far less radical than many productions of operas and plays that are faithful to the scores or texts while imposing radical new concepts or recontextualisations. In London and Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare’s plays have often been performed in modern dress or different periods, with changes of gender and nationality; the latest London production of Wagner’s The Valkyrie (November 2021, English National Opera) has Wotan and the Valkyries in anoraks, with Valhalla as a ski chalet.

Did you advise on Rojo’s revised scenario at all, Doug?

Fullington 13. To my knowledge, Tamara Rojo developed the story for the recontextualization of Raymonda. She explained her ideas when she contacted me and asked if I would be willing to meet with her at Harvard and go over the contents of the Raymonda notations.

Konaev 13. I just want to remind people that a decolonized, anti-Orientalist - in a sense criticizing white supremacy - recontextualization of Raymonda had already been presented at the Kirov Theatre in 1938, with Vasily Vainonen as a choreographer, Valentina Khodasevich as a set-designer and Yuri Slonimsky as a dramaturg. In that production, Raymonda was finally disappointed with a mean cold crusade Koloman and married Abderakhman, who was shown as kind, trusty and good.

The Kirov conductor Yuri Gamalei recalled that its new dances were extremely musical but that its restructuring in general didn’t fit the music (for example, it concluded with Glazunov’s 2nd act), although the audience was excited by the action and actors. Vainonen kept only few of Petipa’s dances.

Macaulay 14. Sergey, I either knew nothing about this or forgot everything about it! How fascinating. Thank you.

Tell me more about your work with Rojo, Doug.

Fullington 14. Tamara was interested in knowing the original choreography (or something close to it — the notations were made around 1903 when Olga Preobrazhenskaya took over the title role). I was interested right away. I love Raymonda and am nearly always delighted to work with someone who wants to know about the contents of the notations.

Tamara was very impressive. She had a clear vision of what she wanted to do, and she was also always respectful of me and my abilities as a reader of the notation. I was engaged as a consultant for the production, which has most often been my role in working with companies that want to utilize Stepanov notation.

Macaulay 15. You came to London in summer 2019 to stage the Raymonda dances for English National Ballet. Were you working with dancers chosen by Rojo?

Fullington 15. I worked only with Tamara and ENB ballet master Renato Paroni de Castro. We spent a wonderful five days at the new ENB studios in August 2019, working through the notated classical dances from the ballet. Tamara was terrific — she was fully engaged and she danced everything full-out and on pointe. I had asked Kyle Davis, a principal dancer at PNB in Seattle, to join me for this project. Kyle has a real gift for transferring notated dance from page to body and has been my longtime collaborator. He helped demonstrate steps and joined Tamara in dancing through everything as we worked together in the studio. Our sessions were filmed, and Tamara was then able to utilise the material in whatever way she chose for her production.

Macaulay 16. As Doug and I have discussed before with Alexei Ratmansky in context of The Sleeping Beauty, there are many features of 1890-1910 Maryinsky style that any stager must consider. Some people allow - indeed wish - the higher extensions and retirés of today, the more extensive use of pointwork, the different notions of the male vocabulary. Did you and Rojo discuss this in advance? Did you allow her to decide the degree of historically informed style?

Fullington 16. I tried to show exactly what was notated, including leg height and all other details. We didn’t often discuss how it was similar or different to choreography or tastes today.

Macaulay 17. After your time here in 2019, coronavirus changed world history. Are there ballet masters at ENB with whom you’ve entrusted the choreography?

Fullington 17. My work on the production, which was solely to provide source material from the Stepanov notations, concluded after that week in London.

Macaulay 18. What contributions if any have you been able to make to the production since 2019?

Fullington 18. I recently participated in a Zoom interview for ENB’s promotion of Raymonda. I discussed the notations and my work with Tamara.

Macaulay 19. The quality and detail of the Stepanov notation seems to vary from one ballet to another, and to have empty patches in each. What’s the quality of the Stepanov notation for Raymonda? Who was the original notator? When did the notation occur? How much does it leave upper body movement up to your imagination ? Where does any stager have to create or guess new material ?

Fullington 19. The notation of Raymonda is a fairly typical example of the Stepanov notations held at Harvard and includes steps (mostly only legs and feet), ground plans, and prose pantomime and action instructions. Nikolai Sergueyev is the scribe for nearly all of the dances. Based on the names of the artists listed in the notation, we can determine that the notation was made around 1903 (see above).

Konaev 19. There are some exceptions. Sergueyev’s archive includes a number of the notations (mostly of variations) of the highest quality, fully detailed, beautifully done – made by Alexandra Konstantinova before or after she graduated from Theatre School in 1905. Among them – the Pizzicato from Raymonda.

Macaulay 20. Can I pause here to ask about Nicholas/Nikolai Sergueyev/Sergeev/Sergueyeff? As you know, sources have always differed about him him, in Russia and the West.

Doug, when I asked Alexei Ratmansky and yourself about him apropos of The Sleeping Beauty in 2015, he and you sang Sergueyev‘s praises; Ratmansky could cite period sources who admired Sergueyev’s work. But both he and you are much more impressed by Henri Justamant when it came to our Giselle questionnaire: it seems that Sergueyev there was far less poetically or imaginatively involved, far more interested in crude or even violent effects.

Sergey, Doug, how do you view Nicholas Sergueyev in view of Raymonda? And how do you see him generally?

Konaev 20. He wasn’t a poet at all. His lack of poetry was his strength and defeat. I treat him as a careerist with ambitions capable to organize and introduce in practice such large-scale project like notating the entire repertory. As a choreographer and dancer deaf to the demands or responses of the contemporary, with no sense of what is outdated and what is not.

That could be a stigma, a sentence, a nightmare for any creative person. It turned out to be great in the long perspective, however, for ballet and for founding ballet in the U.K. and on the West. Anyway, theatre is a collective art, not fully covered neither by notations, nor by video - it’s better to have as many sources and documents as possible.

Fullington 20. I agree with Sergey and would add that the extant notations and other documents in Sergeyev’s hand that are part of the Harvard Collection (and elsewhere) attest to his competence as a notator.

Macaulay 21. The original Raymonda scenario is by Countess Lydia Pashkova. To my mind, this is very much in the Gothic/Romantic vein of Mrs Radcliffe’s once hugely popular novel The Mysteries of Udolpho, (1794), a proto-Romantic thriller that Jane Austen fondly laughs at in Northanger Abbey. What can you tell me about Pashkova?

Fullington 21. Not much. She was a journalist in St. Petersburg and is also credited with the librettos for Petipa’s Cinderella (1893) and Bluebeard (1896).

Konaev 21. Lydia Pashkova, or Paschkoff, née Glinskaya, born in 1850 and died in 1917, was a female writer, a traveler, a member of the French Geographic Society who possibly did a circumnavigation of the globe; she was a correspondent for Le Figaro, a playwright, a librettist – an ideal person for herstory. The book of her novels appeared in the 1870s, if not earlier. In her novels written in French and published in France (though she also wrote in Russian), she focused on women characters and women rights, their position in Russian, Western and Eastern societies. Her fiction features a new type of woman – independent, well educated, divorced or deliberately unmarried – like Paschkoff herself. Among the most important are Princess Vera Glinskaya, The Divorce in Russia (Un Divorce en Russia”), In the East: dramas and landscapes (En Orient : drames et paysages). Also, In Quarantine is very up to the moment.

Two years after Raymonda’s premiere, she explained herself to Elizabeth Eberhardt, a famous traveler and queer person who had converted to Islam: “You have the same dreamy and passionate character as mine, the same impatience, the same taste for a desert and adventurous life. I paid a high price for this passion for danger and for an independent life. Like Lady Stanhope and Lady Ellenborough, I loved East; like them, I lost my fortune. Yes, it’s nice and exciting to ride a horse“ (“Vous avez le même caractère rêveur et passionné que moi ; la même impatience, le même goût du désert et de la vie aventureuse. J’ai payé cher cette passion du danger et de la vie en liberté. Comme Lady Stanhope et Lady Ellenborough, j’aimais l’Orient ; comme elles, j’y ai perdu ma fortune. Oui, c’est charmant d’être à cheval.”).

Macaulay 22. Pashkova set Raymonda in the Middle Ages, at the time of the Crusades. Jean de Brienne and Andrew II of Hungary were real leaders of the Fifth Crusade, though they were by no means nephew and uncle as in the ballet. (And Andrew was somewhat younger than Jean.) It’s interesting to read about these historical figures with these names, but they get us nowhere with Raymonda.

And I don’t think Pashkova was seriously interested in the Crusades. She keeps her ballet in France, in the time of troubadours and courtly love. My guess is that she was more interested - perhaps with Petipa’s encouragement - in this mediaeval birth of romantic love and the age of chivalry. If this were an old Hollywood movie - think The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) - Olivia de Havilland would be Raymonda, Errol Flynn would be Jean de Brienne, and Basil Rathbone would be Abdérame/Abderrakhman.

I’m aware that Tamara Rojo is transposing English National Ballet’s Raymonda to the nineteenth-century and the Crimean War. The whole anti-Islamic bias of the Crusades may be a good area to avoid today.

But can you speak of which aspects of the mediaeval era you think were of interest to Petipa and/or Pashkova?

Fullington 22. The libretto for Raymonda certainly reflects nineteenth-century Crusades narratives in which Christians are depicted as righteous saviours and Muslims as treacherous barbarians. This should come as no surprise — ballets reflected the mores of their day. Petipa, like other Romantics, was interested in idealized notions about the Middle Ages — chivalry, courtly love, court dance.

Konaev 22. I think it’s a proper moment to explain Lydia Pashkova from her own perspective, from the perspective of her own writings and biography. It’s shocking how this experienced author and traveler is still treated by ballet researchers – mostly like a person made problems to Petipa and needed to be completely replaced by choreographer. But it was Pashkova who proposed the plot and Petipa is actually the last one of the contributors after her and Vsevolozhsky.

First of all, Pashkova, while being Christian, deeply respected Islam, stating that high principles of both religions were kept by very few devoted believers. In one of her novels, she noticed that a “true Turk” is a rarity and explained further that by “true Turk” she means “Turk believing in God and his Prophet and following thoroughly the prescriptions of the Koran. Obviously, most of the inhabitants [of Lebanon] have now instead of their religious feeling burning hatred towards the Christians, hatred caused and fuelled by the behaviour of many avid greedy Europeans came to Lebanon for their own good, not for doing much good for Turks of the philanthropy.”

Pashkova’s Raymonda is actually a rearrangement of her semi-autobiographical novel Hannah Pacha published in 1880. It’s a kind of self-portrait in a guise of Comtesse Zoé Azourine travelling to Erzurum, a city of Ottoman Empire, and meeting there two powerful dignitaries, Pasha Hannah and Osman Effendi, both passionate, enlightened and courteous, both Muslims, both admiring her. She has a genius sympathy to Hannah, but his position is precarious. And she thinks that Osman is a proper husband, rich, influential, independent, for completing her mission – to grant Turkish women the same rights and equality with men as Russian women have. However, she preferred to stay independent up to the last scenes of the novel.

There is a scene in Hannah Pacha that sourced and fuelled the second act of Raymonda in many moments and details: such as the Pasha expressing his love and thirty dancers and musicians sent by Osman Effendi to entertain the countess. And in the final part, there is a moment when Osman wants to take her by force (not kidnapping but saving her amidst massacre of Armenians), but she takes the pistol and threatened to kill herself if he ever touched her because she loves Hannah.

There is a photo of Pashkova with a sword – like that famous photo of Pavel Guerdt. His appearance as Abderrakhman is also important, because he, Guerdt, the eternal premier of Imperial Ballet, specialised in noble heroes.

It’s evident that this story couldn’t find its way on the Imperial stage without the transformation required by censorship, without the informal traditions that prevented any reality to appear on ballet stage and the structure of ballet spectacle. The key - twice opened for Pashkova in Imperial ballet - was a French entourage. In each of her previous two ballets, the key was a 1697 Perrault fairytale (Cendrillon/Cinderella and Barbe Bleu/ Bluebeard): this would call for costumes designed by Vsevolozhsky and for mediaeval sets as the production department of the Imperial Theatres and set-designers understood mediaeval style. In the 1890s, it wasn’t Petipa who introduced the French theme in the repertory: it was Vsevolozhsky, the director of the Imperial Theatres, a great patriot and connoisseur of monarchic France, especially the France of Louis XIV and its visual style. Vzevolozhsky wasn’t unique in this approach; the same position was held by many Russian aristocrats, speaking French better than Russian. Under Alexander III and later, it was also a part of his Fronda – like his caricatures, very evil and precise, mocking narrow-minded ministers and political consultants of Alexander III.

Many ballets staged in 1890s and Tchaikovsky’s opera The Queen of Spades (to which Petipa contributed dances) included a scene with a youth playing and some older authoritative person intruding and keep asking them to stop; so did “Raymonda”. The French entourage in Raymonda was aimed to please Vsevolozhsky, but the drama proposed by Pashkova wasn’t typical for Petipa. As in Bluebeard, Pashkova’s focus is a handsome, seductive and abusive male aggressor, a person in power.

Did any other traces of the original Pashkova story survive on their way from novel to ballet? Both in Bluebeardand Raymonda, the leading man is absent for a long time, which can be interpreted as the borders of independence allowed to woman by the ballet in the 1890s.

In my opinion, the character of Andrew/Andrei II was a pretext to unfold Hungarian dances, not the other way. We still have very limited knowledge about decision-making in Imperial Theatres. The logic and content of their ballet repertory is very complicated.

But the Hungarian theme was finally the reason why Raymonda wasn’t performed during World War I when any plays, operas, ballets and even dances associated with the countries of Axis powers were banned at Imperial Theatres. Thus, in 1914-1917, together with Raymonda, all Czardases etc were banned in all other productions that remained in the repertory.

Macaulay 23. Sergey, almost everything you’ve written here is a revelation. Thank you.

As we’ve said, Tamara Rojo’s production, as I’ve already said, Pashkova’s scenario is updated and transposed to the Crimean War, with Raymonda as the Lady of the Lamp, Florence Nightingale. What would you like to say about this?

Fullington 23. I’m not opposed to recontextualized scenarios. I find Tamara’s narrative to be thoughtful and rather ingenious — her story is set in the nineteenth century, the period in which the ballet was created. She told me she wanted to involve England in the scenario as well as a political situation in which England and the Ottoman empire were allies. This would remove the original good guy-bad guy characterisations of the Jean de Brienne and Abderrakhman characters.

Konaev 23. My studies showed that Raymonda is the least loved and the most problematic of the survived Petipa ballets to the West audience. From the music to the action. Historically, it was the choice of such charismatic artists of genius as Anna Pavlova or Rudolf Nureyev that made critics and audience to accept Raymonda – as their whim. Nureyev added a sportive dimension to reinforce it in the repertory. There is a lack of staging and interpretations. But I found the feminist perspective, given the exceptional life of Lydia Pashkova, maybe gave Raymonda more perspective – and the same for other large-scale classical ballets.

Macaulay 24. Thank you. I’ve been wondering whether we should see Pashkova as something of a feminist. This helps.

Whereas it’s hard to find much psychological depth in the Aurora of The Sleeping Beauty, let alone the Sugarplum Fairy of The Nutcracker, Pashkova devised a Cinderella where the heroine (Pierina Legnani) seems to have had real pathos, suffering at the hands of her family, and a Bluebeard where the heroine Ysaure (Legnani again) is married off against her wishes to Bluebeard, a man who proves to be a serial wife-killer. Now Pashkova devised Raymonda, in which the heroine (Legnani, yet again) is left all too vulnerable: her Crusader fiancé is not there to protect her when the Saracen Abderakhman tries to abduct her. No, this is far from radical feminism, but it does show a sympathetic view to the situation of most nineteenth-century women, who were married regardless of choice or affection.

An important element - it seems to me - is that Raymonda sleeps and dreams: we see her dream, which enters straight into psychological/erotic tensions. Usually the dream scenes in the old ballets are dreamt by men. Is there any serious precedent for a woman dreaming? (I understand that, though most Nutcrackers show us Clara’s dream, the 1892 original left t unstated whether the audience was seeing her dream or simply a new plane of reality.)

Fullington 24. That’s a very interesting idea and one I’ve not considered. Vsevolozhsky and Petipa made revisions to the libretto, so it is probably not possible to know who contributed what. No dreams dreamt by women in ballets come to mind at the moment.

Macaulay 25. In the published programme for the English National Raymonda, the historian Jane Pritchard has written that Pashkova “wrote that if <the idea of a Crusades theme> did not appeal for a ballet, she could come up with a narrative based on the Crimean War.”

On reading this, I wrote to Jane to ask for more details on your behalf.

She replied: “In respect of a Crimea ballet my reference was Nadine Meisner’s biography of Petipa p.249 – the quote ‘But if [the submission] doesn’t interest you, throw me a line for a Crimean ballet’ and she found it at the Bakhrushin GTsTM, fond 205, ed. khr.38 I give the reference so Konaev may check it. Now I appreciate it does not actually reference the conflict but given the Crusades and the 19th-century Ottoman Wars have much in common it is possible to interpret the comment in this way. And I admit very convenient! I must admit the editor added the word ‘War’ my text was not as specific. If there is a different interpretation from the Russian side, I’d be happy to learn it.”

Sergey?

Konaev 25. I have a copy of this letter of Pashkova to Petipa. I've checked Nadine's book - her account is correct, whereas I feel Jane's (as edited) misrepresents Pashkova and Nadine. (I greatly admire much of Jane’s work, let me add!)

First, Pashkova’s letter to Petipa (written in French, of course) is dated September 2, 1898 - after the premiere of Raymonda. Further, Pashkova tries to convince Petipa that “un criméen ballet” (a Crimean ballet)” is very actual - but it has nothing to do with what was most shameful defeat of Russian Empire in the 19th century. She's talking about an idea of the ballet with action set in heroic times; she mentions Greeks, Romans, Mithridates et al. and there's not a word on the Crusades (in this particular letter). She's going to consult the book (Petipa might like that) and so on. Nadine’s quotation leaves some words missing as a [ ] space, but Jane in the program has replaced it with [Crusades theme], which is a distortion because Raymonda had been premiered months before. Nadine, by citing this letter, only wanted to show that Pashkova was a very persistent person who wanted to develop a collaboration with Petipa further. Also, "a Crimean ballet" ("un Criméen ballet") is just mentioned in her citation without any explication. Pashkova's ideas - something from the remote heroic past of Mithridates and others (“sujet dans les temps anciens et héroïque”) - include an allusion to Racine. She's going to consult the books and tries to convince the choreographer: “On a peu prèt le sujet qu'a traité Racine." Her letter is written from Crimea, by the way, from Yalta.

It’s very unlikely anyone would have proposed that the Imperial Theatres present anything about a serious and relatively recent military setback such as the Crimean War. In Prince Igor, the Russian Imperial Theatres did have one opera about Russian defeat, but that opera had been commenced by Borodin in the 1870s - he had died in 1887 - and its subject, the unsuccessful and inglorious military defeat of Prince Igor, was set in ancient times. Censorship banned any direct association with anything upsetting for high circles; and Petipa unlike his distant predecessor Didelot couldn't do such productions. His response to the Balkan wars was Roxanne, a slavic adaptation of Giselle.

Macaulay 26. Rojo could have adapted one of the various Soviet texts of Petipa’s Raymonda dances to suit her Crimean War scenario. Instead she’s using your account of the 1898 ballet. Doug, are there advantages to this cleaned-up Petipa for her, can you say?

Fullington 26. To be very specific, Tamara has used some of Petipa’s 1903 production of Raymonda (as notated primarily by Sergeyev and revived by me) as source material. I always believe that consulting the source, where possible, provides the best basis for a staging, even one in which the source material serves only as a guide.

Macaulay 27. Regardless of the ENB production, to what degree does Petipa seem to be imagining or re-creating a mediaeval style in Raymonda?

Fullington 27. Very little that I can tell. Petipa’s notated step vocabulary for pastiche historic dances in Raymonda is similar to that found in other historic dances in his other ballets (The Pupils of Dupré, for example). Medieval style was indicated mostly in the scenic and costume design.

Konaev 27. Petipa always did his homework well. He thoroughly studied visual sources, books, catalogues, etc. We know for sure that there are many pages from L'Univers. France: dictionnaire encyclopédique (par M. Philippe Le Bas. Paris, Firmin Didot frères, 1845) survived in his archive – mostly the portraits of kings of France.

Macaulay 28. We’ve mentioned Petipa’s interest in historical dance. A sequence that has sometimes enchanted me in Russian productions is the brief one in Act One before Raymonda falls into sleep and dreams. She is with her two friends Henriette (originally, in 1898, Olga Preobrazhenskaya) and Clémence (Claudia Kulichevskaya) and the two troubadours Béranger (Nikolai Legat) and Bernard (Georgy Kyaksht). Those four perform a Romanesca, a quasi-mediaeval dance: It can be a wonderfully peaceful and charming moment. (The word “Romanesque” is striking. Pashkova, Glazounov, and Petipa were taking ballet back to the roots of romantic art, the cult of romantic love and chivalry.) How much evidence does the notation give us for Petipa’s original here?

Fullington 28. The notation for the Romanesca is pretty sparse, providing mostly floor plans and only a few basic steps. If I were to revive the dance, I’d look at footage from the Russian productions and see how it matches what little the notation tells us.

Macaulay 29. The most famous part of Raymonda is the grand pas classique hongrois in Act Three, the wedding divertissement in Hungarian-classical style. I suppose that this was in the tradition of nineteenth century composers (Chopin, Liszt, et seq.) taking national dances as the basis for classical compositions.

And I suppose that, for Petipa (and perhaps for his choreographic predecessors?), this was part of showing how classical ballet was the great mainstream into which other dance tributaries flowed. Raymonda Act Three shows mazurka and czardas, then it shows the central characters and their retinue dancing classical variations on those folk/national dances. We know that in Don Quixote Petipa classicises Spanish dance, but is the scale of the classical-Hungarian suite in Raymonda larger than any other such sequence?

Fullington 29. I think Petipa did what he knew, which was to adapt (or incorporate adaptations of) national dance into an academic dance context, something that had been done for decades by his predecessors. Lisa Arkin and Marian Smith have written brilliantly about this in their essay, “National Dance in the Romantic Ballet.” The Pas classique hongrois in the last act of Raymonda involves 18 dancers (Raymonda, Jean de Brienne, and eight male-female couples) and is comparable in size to the cast of Petipa’s 1881 Grand pas in the final act of Paquita, which involves 16 dancers (Paquita, Lucien, six soloists, and eight coryphées) and combines elements of Spanish and academic dance.

Macaulay 30. There are many performing traditions of Raymonda, each of which has its devotees.

In 1946, Danilova and Balanchine staged the three-act ballet for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo: the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts has Victor Jessen’s film of this (c.1948 or later), though Acts One and Two are extremely abbreviated. Balanchine then made three one-act adaptations of the ballet: Pas de Dix (1955), his staging of the Act Three Grand Pas Classique Hongrois and his closest to the Petipa original; Raymonda Variations (1962), his free and plotless imagination of dances from Acts One and Two; and Cortège Hongrois (1973), his free revision of Petipa’s Act Three wedding divertissement , showing both the czardas dances and the Grand Pas Classique Hongrois, all further amplified by material from Acts One and Two.

We have also the Kirov three-act production and Yuri Grigorovich’s 1984 Bolshoi three-act production. Rudolf Nureyev staged the three-act ballet several times in the West (most notably for the touring Royal Ballet, for American Ballet Theatre, and for the Paris Opera Ballet), each time getting further from the Petipa original; I’m fond of his 1966 Royal Ballet staging of Act Three, but much of that seems fairly close to the original.

Oh, and there have been stagings by Anna-Maria Holmes, a Canadian who had extensive access to Soviet ballet in the mid-twentieth century. And in 2014, American Ballet Theatre presented Raymonda Divertissements, an adaptation of the Act Three dances by Irina Kolpakova (a classic Raymonda herself in her Kirov performances of the complete ballet) and Kevin McKenzie.

Which of these do you know? Have any of them been useful to you to get an idea of Raymonda?

Fullington 30. Videos of the Bolshoi and Kirov/Mariinsky versions gave me a sense of the entire ballet early on in my research, but they were clearly missing most of the ballet’s pantomime and included revisions to Petipa’s choreography as well as new choreography.

Balanchine’s Raymonda ballets are fun because he quotes Petipa’s choreography here and there, sometimes setting the choreography to a different passage of music than Petipa did. The 1946 Raymonda is special because it’s Balanchine’s first (mostly) complete restaging of a “classic” in the United States and a collaboration with Alexandra Danilova (one they would repeat nearly thirty years later with Coppélia for New York City Ballet). I’ve examined the scores for this production, corresponded with Robert Barnett about it, and spoken with Patricia Wilde. And Lynn Garafola has recently written about the production in Ballet Review.

Macaulay 31. Am I right to say that the Kirov and Bolshoi productions made important changes to the ballet’s structure and scenario?

Fullington 31. On the whole, these productions cut the narrative by eliminating pantomime. In the Mariinsky production, for example, these cuts include Countess Sybille’s description of the White Lady (who is cut altogether), Raymonda’s instructions to the court to prepare a cour d’amour to receive Jean de Brienne, and Abderrakhman’s frequent mime statements made to the audience that bring us in on his plan to abduct Raymonda.

This approach, in my opinion, renders much of the ballet flat and benign. The Bolshoi version is similar in this regard (and has also now cut the White Lady). Jean de Brienne, rather than Abderrakhman, appears in the opening scene, and Abderrakhman’s role is changed from a mime role to a dancing role. Some of the music intended for mime is choreographed.

Konaev 31. I’d add that the narrative changed its character. Yuri Grigorovich, who directed the 1984 Bolshoi production, was always good in unfolding evil, tragic, dance murals (and as a Soviet choreographer was frightened by this gift of tragedy, of distraction, of showing unpleasant suffering, of individual passions and dark desires hidden deep inside in human's nature), and he treats Raymonda this way. (Soviet ballet was always anxious to enhance the space for the male dancers.)

If a creative artist looked into that dark side, he couldn't consider himself fitting in as Soviet "normal". The idea of what is normal was stable from the 1930s on: a positive view, rationality, collectivism. But the sanctions for those who didn't fit changed from harsh in the 1930s to virtual in the 1980s. Grigorovich, even before he faced official criticism in 1969 for cancelling the Soviet happy ending for Swan Lake, earned the right to show destructive feelings, as he did in the first two acts of The Legend of Love, which finally made "normal" Soviet in the third act: its hero finally is anxious about getting water for people, rather than diving in the personal hell of love affairs. With a few exceptions, prolific Soviet choreographers and theatre directors used to suspect themselves (or just knew for sure) of inclinations towords unwelcome things like formal experiments or studying dark passions; they were constantly ready for self-confession, chattering and exchange: “here I'm doing what you, as a state, want me to do, there you allow me to cross the borders and make look that nothing strange happens.”

I regret that Gorsky’s version is completely unknown on the West as is Lavrovsky’s production as filmed with Nina Timofeyeva as Raymonda. It’s a common knowledge that Gorsky began to folklorise the Hungarian dances of Raymonda; he amended their character, replacing aristocratic postures and gestures with so-called peasants, albeit Hungarian.

Hungary did a wonderful job for notation with Laban’s system, preserving and analyzing the country’s dance heritage. I found the perspective of such analysis, in relation to Petipa’s and Gorsky’s ballets, important and potentially fruitful.

Finally, it was Békéfi who made Hungarian dances a natural part of classics. The scholar Laura Ormigon has found genuine authentic movements in some Spanish dances that Gorsky composed and documented before he could see them in person.

Macaulay 32. In 1984, I asked Frederick Ashton if he had ever considered choreographing a complete Raymonda around the bits of Petipa choreography that were then known to him. He replied “When I looked at the story, it involved a White Lady. The only White Lady I knew was a cocktail.”

Can you talk about the White Lady in the Petipa original? She’s been omitted by some of the later productions - though my good friend Joy Williams Brown, now in her nineties, was the WhIte Lady in the Danilova/Balanchine 1946 production for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo!

At the end of the long first scene, the White Lady comes to life and summons Raymonda from sleep, or into another plane of consciousness. I may be pushing a point, but to me she recalls a particular ghost figure in Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, the Marchioness de Villeroi, a figure who proves to have been the heroine’s aunt and whose unhappy life makes her in the afterlife a protecting figure for the heroine. Ballet-centric people are more likely to see her as a relation of the Lilac Fairy. (Who in turn may be a descendant of the protective deities of epic poetry: Pallas Athene the protecting goddess who looks after Homer’s Odysseus, Venus the one who looks after Virgil’s Aeneas.)

Fullington 32. The White Lady is something of a patron saint—the ancestral protector of Raymonda’s family. She appears in the opening scene, emerging from a statue to lead Raymonda onto the castle terrace to witness her dream in the second scene. And she appears briefly at the dramatic climax of the ballet at the end of Act Two. Glazunov gave her a musical motif, which increases the impact of her presence in the narrative.

Macaulay 33. Raymonda’s aunt, the Comtesse de Doris, is a character who, if given the right mime, helps to set the scene in Act One. Can you describe her? She has the tricky mime speeches about the White Lady.

Fullington 33. Raymonda’s aunt, Countess Sybille, encourages industry, fulfillment of duty, and hospitality. She has the ballet’s big mime narrative in the opening scene, during which she explains to the young courtiers that the White Lady is the protector of the House of Doris.

Macaulay 34. One of the richest and most tantalising problems in any Raymonda is the Saracen hero Abderrakhman or Abdérame, originally played by the prestigious Pavel Gerdt/Guerdt. He proves to be a villain in the plot, but he has the most intoxicatingly seductive music in the ballet.

I’ve read that Pashkova and Petipa originally introduced him in the Act One dream scene, turning her romantic fantasy of Jean de Brienne into nightmare with Abderrakhman‘s arrival - but that Pavel Gerdt, knowing his own high status at the Maryinsky, insisted that his character should not make his first appearance in a nightmare; so we see Abderrakhman in real life in the first main scene of Act One.

And Glazounov gives him this thrilling, gorgeous melody, especially in the adagio of the great Act Two grand pas de six classique. What do the sources and early writings suggest about this highly ambiguous character?

Fullington 34. Abderrakhman is not only the villain in the story, he is the main mime in the ballet and the only character to show any kind of real determination or drive. In addition to his conversations with the other characters, he often brings the audience into his confidence by sharing his plans with them in mime.

I think his surprise introduction in the ballet’s second scene was genius. In my opinion, the change to include him in the opening scene creates dramatic stasis. But it seems he was added to the first scene before the premiere: this was incorporated into the published 1898 libretto. I think the idea is that Gerdt deserved to be introduced earlier in the ballet. Yes, Raymonda was to meet him first in her dream, which was a vision shown her by the White Lady.

Macaulay 35. So I’m confused by the various productions I’ve seen. Where did Abdérame/Abderrakhman first appear in the 1898 production? When was he added to the opening scene before Raymonda’s dream?

Fullington 35. The initial plan was that he appeared as a surprise during the dream scene, but before the premiere, he was given an earlier entrance during the first scene. This was incorporated into the published libretto.

Macaulay 36. Did you teach all the mime to Rojo and Paroni at English National Ballet?

Fullington 36. No, we didn’t address mime at all.

Macaulay 37. I’ve seen four or more complete productions of Raymonda without seeing any mime I can remember. How much does it change the action? You’ve said above thiKat Abdérame/Abderrakhman does most of the mime.

Fullington 37. The mime helps define the personalities of the characters. Without it, non-mimed action must be introduced or the characters are left to gesture vaguely and smile blandly at each other (as they do in several productions I’ve seen). Abderrakhman engages the audience by miming his feelings and intentions to them.

Macaulay 38. Would a period Raymonda feature mime gestures a London audience would find unfamiliar? I remember that both the Royal Sleeping Beauty and the Kirov/Makarova Bayadère have gestures I’ve never seen elsewhere. (The Royal’s Lilac Fairy addresses Carabosse with a speech including a tragic knife-into-breast gesture few can translate. Monica Mason told me it’s saying “Your words plant daggers in me.” The Bayadère has two or more uses of a crushing gesture which says “Destroy!”: it’s fabulously hammy.

With Raymonda, do you know which gestures should be used at each moment? How do you mime “White Lady”, let alone mime her ancestral significance to Raymonda’s dynasty? Do all the speeches of Abderrakhman/Abdérame use gestures we can be expected to understand?

Fullington 38. I presume mime included standardized gestures and those developed by the dancers and actors to communicate unusual or particular words or phrases that made up their “lines”. Sergeyev wrote mime conversations out in prose, the syntax of which often suggests the order in which the mime gestures may have been delivered, but rarely are mime gestures described. Floors plans usually indicate where characters are on stage when miming.

Macaulay 39. So in the case of Raymonda, where the ballet’s performing tradition is devoid of mime, would a modern stager have to work out all the gestures, their phrasing, and their musicality?

Fullington 39. They would, yes. Useful sources to assist with this are the published scores (orchestral score and piano reduction—these include printed annotations) and the choreographic notation.

Macaulay 40. You and Marian Smith are great believers in mime, as (with reservations) am I. Am I right that the mime in the old ballets is not notated in terms of movements, let alone in terms of musicality?

Fullington 40. The Justamant manuals also include prose conversations that were delivered in mime and drawings that show dancers’ placement on stage and sometimes their particular body positions. Annotated répétiteurs (music rehearsal scores) sometimes include mime phrase written into the score that help us know which phrases of music were meant to accompany a particular passage of mime.

Macaulay 41. It became important for ballet composers to know how to compose good music for mime and indeed for all changes of dramatic action. Our recent correspondence about Giselle has sharpened my ear for how Adolphe Adam’s music clearly moves from character to character, from mood to mood, and how it helps to tell the story of mime scenes. It’s quite a gift: I would rather see Odette in Swan Lake mime her story to Siegfried but I can see why Diaghilev, Balanchine, and others replaced her speech with a dance passage: Tchaikovsky hadn’t learnt how to write the right kind of mime music in Swan Lake, whereas he had in The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker. How effective do you think Glazunov was in writing music to accompany non-dance music for mime and other dramatic action?

Fullington 41. Glazunov effectively used recurring motifs as the primary accompaniment for mimed conversations as opposed to music that more closely hewed to the action (such as Adam wrote for Giselle). These motifs become cues for the audience that can help them make sense of the story.

Macaulay 42. There are several styles of mime. The Royal Danes have had a healthy tradition, often very light and intimate in style. The Maryinsky and Bolshoi, who have removed mime from several ballets in the Soviet era, have a more grandiose, ponderous, and heavily legato style in such works as Bayadère. And I guess the Royal British is related to both the British class system and to the British sense of character acting. I’m making quick, crude notes on complex areas here. Do you have much sense of how mime was or wasn’t performed in Petipa’s day?

Fullington 42. (I addressed this a bit in my reply to question 38.] As far as mime gestures, my best idea comes from those passages that have been handed down (for example, the Prince’s mime in Act Two of The Nutcrackerthat we have in Balanchine’s version). We know from staging manuals and choreographic notations that artists often came down to the footlights to mime, especially when they were addressing the audience (for example, Hilarion in Giselle). Photographs suggest silent-movie types of facial expressions were common as were active positions of the body (bending and leaning the body, inclining the head, etc.). In the French ballet scores of the mid-nineteenth century, such as Adam’s for Giselle (1841), the music hewed closely to the action and mime, as Marian Smith has made so clear in her book, Ballet and Opera in the Age of Giselle, and therefore it would make sense to align mime gestures with certain notes or beats in the music that were intended to give voice to a particular word or phrase. Scores later in the century became for motive-based, especially Glazunov’s score for Raymonda, and contained fewer direct references to particular words or phrases. Whether this impacted the rhythm or pace of mime I cannot say, but the nature of the music of such later scores suggests latitude in mime delivery may have been possible.

Macaulay 43. Today, each company tends to perform mime with much the same musical precision as with dance - this gesture on this note, and so on. But since the musical timing of the mime is not notated, should we presume that Petipa gave considerable musical freedom to his interpreters with mime timing?

Fullington 43. In the French ballet scores of the mid-nineteenth century, such as Adam’s for Giselle (1841), the music hewed closely to the action and mime, as Marian Smith has made so clear in her book, Ballet and Opera in the Age of Giselle, and therefore it would make sense to align mime gestures with certain notes or beats in the music that were intended to give voice to a particular word or phrase. Scores later in the century became for motive-based, especially Glazunov’s score for Raymonda, and contained fewer direct references to particular words or phrases. Whether this impacted the rhythm or pace of mime I cannot say, but the nature of the music of such later scores suggests latitude in mime delivery may have been possible.

Macaulay 44. Raymonda’s entrance is evidently designed to create a glorious impression, though I have known it underwhelm. Can you tell me what Petipa seems to have planned?

Fullington 44. Raymonda’s entrance, like Aurora’s, is a brief petit allegro variation. During it, she picks up flowers that the courtiers have placed in a path on the ground. Petipa notes that Raymonda should exude joy.

Macaulay 45. The big event of the first scene is the grande valse - is this a valse villageoise? How many dancers did Petipa employ here? Is most of this a dance along the lines of the Sleeping Beauty Garland valse and the Swan Lake first-act valse, as Ratmansky and others have realised them?

Fullington 45. Yes, the big waltz in the first scene is similar to those in Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, and the 1895 Swan Lake. It originally featured 24 male-female peasant couples who danced with garlands and wreaths.

Macaulay 46. But it then pauses to become a Raymonda concerto. Glazunov makes a pizzicato variation on the main melody, and Raymonda delivers a subtly virtuoso solo with plenty of emphasis on footwork and pointwork. Then the valse ensemble recommences, but with Raymonda threading her way through it until they all reach a grand conclusion.

Does this choreographic construction recur elsewhere in nineteenth-century ballet: a single number where the corps sets the scene, the ballerina displays herself in high style, and then the corps and she conclude together? I can’t think of all that being part of a single musical item in any other ballet.

Fullington 46. I can’t say with any certainty that this unusual dance structure occurs in no other ballet, but I can’t think of any in which it does. As you describe, the dance, taken as a whole, features a three-part structure consisting of 1) an ensemble waltz, 2) a solo variation, and 3) a waltz coda featuring the soloist and ensemble, all based on the same musical theme. It is the major dance suite of the ballet’s opening scene and foreshadows the longer ones to come.

Macaulay 47. It’s my impression that the Russian ballet theatre of Petipa’s day adored huge processions, the display of vast numbers onstage, sometimes just walking or processing. This seems to be part of Bounonville’s complaint about the Russian ballet he saw on his visit there around 1875; he makes it sound as if Petipa and Christian Johanssen, men from Western Europe who had ended up in Russia, agreed with him, but that they had to concede to local taste.

Really the grande valse in Act One of Raymonda is an example of this. There are many people already lining the sides of the stage, but now this waltz is danced by some thirty-two people - sixteen men, sixteen women. After Petipa, very few choreographers other than Balanchine would deploy so many dancers. I dare say we’ll get a reduced version at English National Ballet; in 1934, Nicholas Sergueyev simply omitted Petipa’s waltz in Act One of Swan Lake and maybe his from Act One of The Sleeping Beauty. What would you like to say about Petipa’s use of large numbers, especially here?

Fullington 47. Petipa had large resources at his disposal and was adept in deploying them on stage. He included processions in many of his ballets, but this was a feature inherited from French opera and ballet (and we again can thank Marian Smith for addressing the popularity and ubiquity of processions in her research). Processions represented grandeur by featuring large casts in lavish costumes. Raymonda’s second act opens with a march in which a large number of participants enter the stage to welcome Jean de Brienne. At the top of the third act, Le cortège hongrois is another procession, this one of wedding guests arriving go congratulate Raymond and Jean. The Act One waltz actually featured twenty-four couples. And Abderrakhman’s suite in Act Two and the divertissement in Act Three featured more than 100 performers each, including students of the Theater School.

Macaulay 48. When Raymonda dances to the pizzicato violin part of that waltz (no longer in waltz time!), we can see straightaway a close connection between dance and music. In the 2011 video I’ve seen of Olesia Novikova, she tends to lag behind the beat: a trait shared by many Russians in recent decades but the opposite of the one cultivated by Balanchine and Danilova. Is there any evidence for how the dancers of Petipa’s era danced to the beat? - anticipating it, hitting it, following it?

Fullington 48. Stepanov notation, which indicates rhythm, suggests that choreography had a literal relationship to music, that dancers moves rhythmically according to the pulse of the music. I’ve always interpreted this to mean that weight should transfer on the beat.

Macaulay 49. So Raymonda has had two dances with flowers at the start of Act One. Is it fair to think that Petipa is showing she’s in the springtime of her life?

Fullington 49. Sure, why not. Flowers figure in many ballets and are often used in both romantic situations and for celebratory occasions.

Macaulay 50. As we usually see it, one of the most ambiguous dances is the Act Two pas de six in which Raymonda, reluctantly, and her two companions Henriette and Clémence dance with Abderakhman and - yes? - the two male troubadours. How clear is it to tell what Pashkova, Petipa, and Glazounov wanted here? Raymonda consents to dance with Abderakhman, who evidently is smitten with her and is putting on a massive courtship act; his music is full of very gorgeous allure. Can we say what dramatic ideas were intended by the makers of the ballet?

Fullington 50. During the adagio of the Act Two pas d’action, Abderrakhman attempts to woo Raymonda with declarations of love and pleas for Raymonda to listen to him. These short mimed phrases are written into the notation of the adagio and I assume were created by Petipa as he choreographed the dance. The music is a development of Abderrakhman’s motif.

Macaulay 51. But tell me what you feel about the expression in the adagio of the great pas de six. Glazounov’s music is so gorgeous that most of us feel he is making a persuasive case for Abderrakhman/Abdérame’s courtship. Is there any evidence that Petipa wanted Abderrakhman to be seriously attractive to us and/or to Raymonda? Or were they both making a yummy role for Pavel Gerdt, now aged fifty-three but still a star and admired artist?

Fullington 51. I think Glazunov was riffing on Aberrakhman's motif in a similar way as other late-nineteenth-century composers who created impressions of the Middle East in their music. The overblown quality of the adagio (to borrow an adjective from Arlene Croce) matches the scope of Abderrakhman's suite (the dozens he brought with him to make an impressive showing to Raymonda). Nothing in the sources I've studied suggests that Raymonda was intended to seriously consider Abderrakhman as an alternative lover to Jean de Brienne or that the audience was expected to view him as anything but the villain of the story. Nevertheless, the role was indeed a yummy one, as you say, for the ever-popular Gerdt.

Macaulay 52. To return to the Romanesca - which happens as courtiers light candles on chandeliers - I suppose this dance for two women (Henriette, Clémence) and two men (Bernard and Béranger) is Petipa’s allusion to the mediaeval danse à deux: the middle ages’ new trend of having dances that were not group line dances (like the farandole) but involved individual men and women addressing each other in a form of courtship. This was an expression of the mediaeval cult of romantic love and the court of love. (The dance historian Belinda Quirey always insisted that this was a far more profound change to human society than the Renaissance.) Any comments?

Fullington 52. [This one is beyond my scope of knowledge, but what you write is very interesting.]

Macaulay 53. It’s all very courteous and elegant; as the Russians have passed it down, there’s a highly cultivated, elegant correspondence between head, foot, arm, and knee. As they dance, Raymonda plays the harp. She’s not the first ballet heroine to be seen playing an instrument (or miming the playing). Can you talk about this?

Fullington 53. The ability to play an instrument was a desired accomplishment for nineteenth century Western women. In La Bayadère, Nikia plays the vina, an Indian stringed instrument.

Macaulay 54. After the Romanesca for her friends, Raymonda dances with a shawl. This is a pas de châle, a dance with a scarf/shawl that is part of a tradition going back (by way of Nikiya in the Bayadère Shades scene) to Taglioni. (Tolstoy in War and Peace marvels at how Natasha has a genetic connection to a traditional Russian folk dance rather than to the imported pas de châle of Western ballet. Hence the title of Orlando Figes’s history, Natasha’s Dance.)

As we see it in Russian productions, this, Raymonda’s third solo, is her most rigorously classical number so far, with two unforgettable demi-fouetté switches of direction from seconde on point to arabesque en fondu.

Though other instruments join the harp, this is one of the quietest, gentlest ballerina numbers in the repertory; and part of its charm onstage is that Raymonda seems to be dancing for pleasure, happy to be with music and friends at the end of a long and splendid day. How precise is the notation here?

Fullington 54. The notation for this dance is much like the notation of others: it provides the ground plan and movements for legs and feet. At a couple of points, annotations tells us that she “throws” her shawl.

Macaulay 55. She dances to the harp. Do the stage notes suggest that her friend Clémence (or any other character) is now playing it?

Fullington 55. The libretto tells us that she hands the lute to one of her friends and later that Clémence plays the lute.

Macaulay 56. The number that follows is even quieter, and has no dancing. Glazunov’s music here , in waltz tempo, always sounds to me like Wagner’s Rhinemaidens going down the drain, though I think he meant it to depict the approach of sleep at the end of the day. As we see the stage action, Raymonda’s friends gently leave her alone. She once more contemplates the scroll that presumably shows her a portrait of her bien-aimé Jean de Brienne. The light falls. She sits and prepares to fall asleep in a chair. It’s hard to think of any scene in nineteenth-century ballet that’s so touchingly subdued: a wonderful counterpart to all the ceremony and spectacle earlier on.

And it shows us a woman rapt in thought: Raymonda is about to dream. What exactly does the 1898-1903 stage action call for here? And are there any precedents for such a passage in the ballets you’ve studied?

Fullington 56. This is the end of the first scene and precedes the entr’acte that will allow for a change of scenery. The notation indicates that the friends remain onstage, having given Raymonda not a portrait but rather Jean de Brienne’s letter, which Raymonda re-reads. She plans to fall asleep and dream of him. Just before the end of the scene, the White Lady appears and leads Raymonda onto the castle terrace.