Patricia Lent, part 3, questions and answers 74-101 on Merce Cunningham

Patricia (“Trish”) Lent is Director of Licensing to the Merce Cuningham Trust. She danced with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company from 1984 to 1993, and with Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project from1994 to 1996. In previous posts (see February 22 and March 12, 2022), she has answered seventy-three questions I’ve sent her. Here she answers a further twenty-eight. (Others will follow.) These questions focus especially on works created in the years 1986-1989 (Shards, Points in Space, Carousel, Eleven, Five Stone Wind, Inventions, August Pace,).

AM 74. Merce the dancer was one of the most talked-of features of your years in the Cunningham company, especially up to 1989. I once asked David Vaughan in 1981 “When will Merce stop dancing?” David replied “When they carry him out of the theatre feet first.” My memory is that he still performed barefoot up to age sixty-two; and his feet were controversial. In 1989, he reached seventy, he finally stopped appearing onstage in every single programme, though he went on appearing in some works in his early seventies (and at age eighty in Occasion Piece, after your departure).

Generally, Merce onstage in his sixties was one of the most controversial elements of his already controversial form of dance theatre. People have always tended to go to dance to see young and beautiful performers – and the rest of you were all young and beautiful. But Merce made little secret about growing old onstage; he forced people to talk about his age. Some people couldn’t stand watching him; others couldn’t (didn’t want to) take their eyes off him. In Pictures, in Quartet (above all!), and in Fabrications, he gave himself amazing roles: people compared him to Shakespeare’s Prospero and to King Lear, to Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya.

Can you talk about what it was like sharing the stage with this great but rugged and no-longer-young performer? Did you ever feel he performed some roles too long? Did you learn about performing from the way he performed? Arlene Croce had written of his great gifts as an actor when he was still in his fifties: did you likewise regard him as an actor? What remained his dance strengths?

PL 74. Over the course of my time in the company (1984-1993), we gave more than 660 shows. By my count, Merce danced in all but eighteen of them. He was performing in four repertory dances when I joined (Roadrunners, Gallopade, Quartet and Roaratorio), and over the course of the next nine years created roles for himself in eight more (Pictures, Phrases, Grange Eve, Fabrications, Five Stone Wind, Trackers, Loosestrife, and Enter). He also danced in every Event. Apart from Gallopade, in which all the dancers wore jazz shoes, and Roadrunners, in which Merce did a comic bit of putting on his shoes, sweater, and pants while avoiding a careening dancer, he performed all these works barefoot.

Merce was 73 when Enter premiered. He performed it (barefoot) for another three years, dancing it for the last time in June 1994. It’s true that in late 1989 there were a few programs during our Sadler’s Wells season in which Merce did not appear. My guess is that he did not enjoy being on the side lines even occasionally, because from 1990 through 1993, Merce danced in all but thirteen shows.

It was not really until 1994, when Merce was 75, that his appearances became less frequent, and even that year he danced in more than half of the company’s shows. He made his final appearance in an Event in July 1997. Even then he did not leave the stage entirely, performing Occasion Piece with Mikhail Baryshnikov two years later, and performing the “Chair Solo” from Loops on special programs in 2000 and 2001. I was not around when Merce stopped performing altogether. I think it must have been difficult and sad for him.

I can’t say that I learned how to perform from Merce, but I learned how to be a dancer. Every day started with class. Every phrase was fully inhabited. Every rehearsal was full out. Every performance, no matter the occasion or the venue, was the best you could do. And every reception was a battle to find a drink and some food and a place to sit down.

During my time, Merce typically arrived on stage an hour before curtain and did a full warm up. So did I. So did nearly everyone else. It was a way of life – training, rehearsing, performing. Unlike Merce, I was an uneasy performer, but because I loved class and loved rehearsal, I loved being a dancer. I think Merce loved being on stage in front of an audience. I think for many years that’s why he had a company. Fortunately for me and all the people who danced for him, he also loved making up steps and choreographing dances. Fortunately for him, when he could no longer perform himself, his passion for making up steps remained.

AM 75. Douglas Dunn, remarking about Merce’s dancing during Douglas’s time with the company, said “Merce always knew the story”. The word “story” should not be taken too literally, I think; but, whatever the work was, Merce onstage suggested a different understanding from that shown by any other dancer - in his eyes, his reactions, his gestures, his dynamics. This connects to Arlene Croce’s 1970s point that he was “a great actor”, in Quartet, above all, the difference between the other dancers’ physically skilled fullness and his physically limitations but intense understanding made for great drama. Having looked at Merce’s notes for most pieces, I suspect he sometimes only came to understand the “story” by creating the dance; but there were others where he began with plenty of “expressive” ideas.

As you know, I loved watching Cunningham dance theatre. And I loved several Cunningham works in which he was absent (Doubles, August Pace) as well as a number of works (Quartet, Pictures, Fabrications, Five Stone Wind, Loosestrife) in which his “differentness” was an issue. Perhaps only in Duets, in “my” day, did he seem to cast himself as just another dancer, one of the larger ensemble.

But I’m curious: did you or your colleagues ever sometimes feel you should try to invest his choreography with the private meaning and acting animation which he brought to it? Carolyn Brown writes of how Marianne Preger and she, in the 1950s, would often make up a story, even if a different one for each performance. Valda Setterfield, despite her actorly stage persona, insists on the opposite - that it was always enough for her to do the movement for its own sake. When I was first watching the Cunningham company, the intensely “acted” facial expressions of Louise Burns were widely seen as a distracting, unhelpful extra layer of commentary. All these examples show that there were choices of how to address interpretation, involvement, Merce-like animation. You yourself certainly seemed an objective performer, delivering the movement for all it was worth but never imposing an opinion; but some of your contemporaries were subtly different. Were these choices discussed by you and/or your generation?

PL75. One day, years ago, during a rehearsal break, I commented that I regarded myself as a craftsman rather than an artist. Merce was the artist, he invented the work. I helped to “build” it. This astonished (and perhaps offended) one of my colleagues who took pride in identifying herself as a “performing artist.”

I didn’t use the term craftsman to diminish my contribution. I practiced my craft with care, expertise, and ingenuity, and I believed what I did in the studio was essential to Merce’s process. But I did not see myself as an interpreter of his work. I often use the word “inhabit” when I speak about dancing the work. That is what I strove to do – to get inside the material, to realize its physical possibilities, to meet the challenges head on, and to make it as expansive and lively as I could. I wasn’t always pleased with my work, but I was clear about the task.

From a less philosophical perspective … sometime in the late 1980s, my aunt and her family came to see a Cunningham performance. This may have been the first dance concert she ever attended. During the intermission a stranger asked her why the dancers weren’t smiling. “They’re too busy to smile,” she replied. There was that too. Merce (and his work) kept me very busy.

AM. I love these answers. Still, as I’m sure you know, the words “artist” and “technician” come from Latin and Greek roots referring to “craft”.

AM 76. Many Cunningham dancers felt that, if a piece was known to be composed by David Tudor (who composed the score for Shards), they would it would be “one of Merce’s dramas” even before they heard the score. Do you agree? What Tudor-Cunningham pieces did you most admire?

PL 76. David Tudor was the greatest composer of electronic music of the 20th century. I say that with complete confidence, although I never had more than a glimmer of an idea what he was doing in the orchestra pit. What I do remember is the extraordinary assortment of equipment on his table – wires, cables, plugs, knobs, dials, switches, pedals. I recently described what emerged from that tangle of devices as a sonic magic act, that’s how it felt. The sound enveloped us, it was dense and layered, and it ricocheted around the theater.

I’m forever grateful that I had the opportunity to dance Merce’s RainForest inside Tudor’s Rainforest, and that I performed Channels/Inserts with Tudor’s Phonemes, and Exchange with Tudor’s Weatherings. I will always regret missing the chance to dance Sounddance with Tudor’s Toneburst. I can’t imagine any of those dances with any other sound aside from the quiet of the Westbeth studio.

AM 77. In general, as you well know, Merce liked the audience to be free to make its own interpretation of each piece. He relished the vast multiplicity of such interpretations in the case of Winterbranch (1964). Yet some of his titles suggest he was concerned poetically with meaning and expressive qualities. And occasionally - Shards (1987) is the ultimate example - he spoke of what a work was “about”, even if we may differ from him. (He said it was about the modern fragmentation of society, and on one occasion spoke of it as a reaction to Ronald Reagan’s inhumane politics. It certainly showed a number of people who seemed never to connect or to communicate, but at times, especially in a solo of decelerating pulse for Rob Remley it also seemed to show nature itself having a nervous breakdown.

You have said that Shards is unlikely to be revived, since it stillnesses were extreme in duration and in rigor. Nonetheless I hope you appreciate that it was an extraordinary piece for many of us. Did you feel that this work was “about” something?

PL 77. I’m pleased to know that Shards resonated with you and others. I think it was a difficult dance for many viewers. It was also challenging to perform. We were all on stage for the entire dance, and although there was always someone moving, there was a great deal of stillness. I was the last of the eight dancers to move. I held my first position for five minutes, and then took another which I held for about 30 seconds, and a third which I held for another 30 seconds. It was six minutes before I did a phrase. We were dealing both with stillness and with separateness – occupying the space at the same time, but not really functioning as a group. At least that was my experience. The still positions meant that our sightlines were often limited. I remember having to listen for footfalls and other movement sounds in order to know where we were in the dance.

AM 78. In which cases other than Shards – if any - did you feel Merce trying to bring out particular meanings or expressive qualities? (Perhaps Doubletoss <1993>?>

PL 78. In my experience, Merce did not coach us to evoke or communicate meanings or emotions. He worked with us on movement, both on the physical action and the physical quality of the movement. For Shards, the movement was about stillness and weight, interrupted by percussive, vigorous phrases. The phrases also rippled through the group – one person would start a phrase, and then another dancer (or dancers) in another part of the space would join. It wasn’t exactly like dancing together, but more like stepping onboard the phrase. As I recall many of the phrases were repeated multiple times, sometimes decelerating or otherwise changing. All this created an atmosphere that was unique to that dance. I understand that. But we were left to experience it in our own way and were not tasked with communicating a message – Merce’s or our own – to the audience.

AM 79. It’s curious that Merce, whose work sometimes contains an expressionist intensity, was also the master of works that were about nothing in particular, perhaps those that Ellen Cornfield described as “just were”. To me, Points in Space is one such, though it’s full of different expressive details. I’m fascinated by the pronounced differences between the TV and stage versions. Your memories and thoughts?

PL 79. Points in Space was a dance for camera, a collaboration with the BBC. In the TV studio in 1986, we were dancing in front of a huge cyclorama, continually changing our facings. There was a lot of slow continuous movement interwoven with scurrying footwork. I did a lot of scurrying. When the dance moved to the stage in 1987, the cast was reduced from fifteen to twelve. Merce eliminated his own part, and rather than replace Megan Walker and Kevin Schroder, who had recently left the company, he reworked the material for a smaller cast. Alan Good (who had danced with Megan in the film) and Cathy Kerr (who had danced with Kevin) became partners in the stage version, and Merce inserted into the dance a duet for them that had been made for Cathy and Joseph Lennon in 1980. This was the Exercise Piece Duet, and it became a prominent feature of the stage version of Points in Space. I expect there were other changes, but those were the most substantial.

AM 80. Merce’s notes for Carousal (1987) are a happy amazement. What are your memories of this piece?

PL 80. Carousal was a commission for Jacob’s Pillow. It was a kind of oddball circus. There were a series of pantomimed vignettes – tightrope walking, tumbling, rope climbing, a magic act – as well as other quirky movement phrases. The space was divided into different rings (like a circus), often demarcated by foam tubing that we carried in and out. The rings near the wings were semicircles, as though they didn’t quite fit on the stage. I remember doing a goofy skipping phrase with Helen Barrow and Karen Radford. We skipped along the inside edge of the semi-circle, one after the other, from the upstage wing to the downstage wing, and then, after exiting, dashed upstage to re-enter again – it was a little gag, as though we were trying to trick the audience into thinking we were skipping in a full circle. I had a quiet, fluid solo phrase toward the end of the dance that was wonderful to do – shoulder circles, crisscrossing steps, twisting and curving.

AM 81. Marc Farre told me that Eleven (1988) seemed to be one of Merce’s great works until it was performed, when the “music” (Robert Ashley) killed it. Your memories of this?

PL 81. Eleven was short lived. It premiered at the Joyce, during a month-long season, and was done very few times afterwards. I remember the costumes (William Anastasi) as remarkably unflattering and the music as a perplexing conversation between two visitors from outer space. I have few if any memories of the choreography.

AM 82. In such cases, would the Trust consider reviving the dance with a new score?

PL 82. I suppose we might if someone had a compelling reason for wanting to reconstruct the choreography for Eleven.

AM 83. RainForest was revived in 1988, when you were in the company.

Have you ever read The Forest People by the anthropologist Colin Turnbull, which Merce said inspired RainForest? The difference between the book and the dance is huge, but nonetheless it suggests that Merce was thinking of the rainforest of the Congo, where The Forest People is set (as well as the rainforest of the Pacific Northwest, which he visited as a child and which he also said gave him the title for this work). And The Forest People is about a tall anthropologist amid the African pygmies: which may explain the opening image, with a tall man standing with a woman curled like a ball at his feet. It may also explain why, as the curtain was about to go up before one performance, Merce said to Meg Harper “We’re pygmies”. She ignored it, because by that point she had her own idea about the role and the movement. But you will have heard, more often than I, how different Barbara Dilley, that role’s originator, was; I think Merce may have been trying to jog Meg into another interpretation of her role.

One or more of its later roles may be more animal than human. How did you feel about yours? What kind of imaginative world did “RainForest” create for you?

PL 83. We did very few revivals during my time in the company. I’m grateful that RainForest was one of them. Merce taught us the dance himself, darting back and forth between his back room (to check the reel-to-reel tape) and the studio. I’d never seen the dance, though I’d heard about it, and my impression was that Merce didn’t want us watching the tape. I like to think that’s because he wanted us to inhabit the dance ourselves, rather than try to imitate the dancers on the tape. I did Carolyn Brown’s role, which started with a vigorous tangly duet followed by a solo dash around the stage. It was wonderful to do, and very different than the work Merce was making at that time. All the elements – Merce’s choreography, Tudor’s music, Johns’s costumes, and the Warhol silver clouds combined to create a magical environment.

AM 84. I remain sad that Five Stone Wind (1988) did not have a longer shelf life in repertory. Your memories of this work?

PL 84. Five Stone Wind was a large-scale full-company work, nearly an hour long. It had a “double” premiere to accommodate the commissioning organizations – first in Berlin as Five Stone, and then a month later in Avignon as Five Stone Wind (this was the same dance with the added “wind” sections). The music operated similarly: Five Stone was composed by John Cage and David Tudor (played by Michael Pugliese and David Tudor); Five Stone Wind was the Cage/Tudor work with Takehisa Kosugi joining partway through.

The dance was invigorating and in spots devilishly hard. It began with lush, sweeping movement – big leg circles and lunges, wide arms, deep curves, tilts, and arches of the torso. Over the course of the dance, the tempo and intensity picked up, ending with the skittery “wind” phrases done at breakneck speed.

We did Five Stone Wind in a variety of places but for me the Palais des Papes in Avignon was its home turf – a magnificent outdoor venue with a “décor” of stone walls, night sky and the mistral. I remember one night the mistral was blowing harder than usual, and my long circle skirt turned into a kind of sail, adding an extra challenge to the slow promenade I was trying to accomplish.

AM 85. Merce’s notes reveal that Five Stone Wind originally had a Russian title (Cyrillic script) which translates as, guess what, Cherry Orchard.

As he once said in a 1997 BAM interview with Laura Kuhn, he based it on entrances and exits in Chekhov’s play, with most roles absolutely connected to Chekhov’s, at least in terms of entrances and exits. But he also adds human “winds”, a title he may have said aloud, since company dancers used it.

I had already written in 1987 and, again, earlier in 1988 about how Chekhovian Merce’s work often seemed to me in the mid/late 1980s, though I’m not sure I ever did so to my own satisfaction. I don’t know if you know any or much Chekhov, but do you feel some connection?

PL 85. I read Chekov’s short stories in college, and I’ve seen several productions of Chekov’s plays, but I’m no expert. I can’t say that I see a connection, but I don’t dismiss the idea either. Merce’s work has an openness that invites connections. Perhaps that’s true of Chekov’s work as well.

I wouldn’t say that the dance was originally titled Cherry Orchard. Merce’s notes often include various working titles that he seems to have used as placeholders before settling on a name. The front cover of one of Merce’s notebooks for Five Stone Wind lists several of these: Berlin/Avignon Express, Inscape, Out Bound.

But there are indeed ten pages written in a combination of Russian and English that have the heading Cherry Orchard in Cyrillic. These pages, which outline the entrances and exits of the characters in Chekov’s play, are followed by a series of pages (in English) with a corresponding plan for the entrances and exits of the dancers, which he identifies as F1-F7 (for the seven female dancers) and M1-M6 (for the six male dancers). So it’s clear that the structure of the dance – the entrances and exits, and perhaps the groupings – derived from the structure of the play.

Merce’s notes also reveal that the “five” in Five Stone Wind corresponds to five (imaginary) camera positions which he used to organize the space. It seems that all our entrances and exits were made in relation to these “cameras. At the time, I was aware that Merce had numbered the entrances and exits in some way, but I assumed this had to with the wings in a theater. Looking at his notes, I realize that those numbers correspond to camera positions (four in each of the four corners of the space, and one upstage center) which we were skirting past on our way in and out.

The “wind” in Five Stone Wind almost certainly refers to the mistral!

AM 86. Merce’s notes had included lines in Cyrillic scripts since 1958 (Antic Meet, which - he told Robert Rauschenberg - is based on aspects of Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov). While you were dancing with the company, were you ever aware of Merce studying the Russian language or literature?

PL 86. I knew that Merce could read and write Russian, but that’s about all. In my investigation of his choreographic notes, I’ve often come across Cyrillic writing, as well as a lot of French. In recent years I’ve seen the early program note for Antic Meet which read: “let me tell you that the absurd is only too necessary on earth – Ivan Karamazov.”

AM 87. Cargo X (you weren’t in it) may have been the most Dadaist work I saw by Merce, with Kosugi at HIS most Dadaist. Any memories?

PL 87. Actually, I was in Cargo X! There were two casts of seven dancers. The newer company members were in one cast, and the senior members were in the other. Merce worked with the newer members first, and then they taught us their parts. I don’t remember whether Merce finished the entire dance with the first cast, and then we learned it, or if the transfer happened partway through. Either way, it was not a very satisfying process for me, and Cargo X was not a favorite of mine to perform.

AM 88. Takehisa Kosugi made the wonderful score for our beloved Doubles, but in general I remember him as the ultimate Cunningham-Cage Dadaist, the musically craziest on the team. What are your memories? What did you most or least admire?

PL 88. I am so grateful to have known and worked with Kosugi. Kosugi and I were “new” at the same time. I was the newest dancer, and he was the newest musician (joining Cage and Tudor). Kosugi was far more accomplished than I at that time, but we shared a similar status within our spheres which I think created a bond. We also shared March birthdays which always fell during our City Center season – a shared chocolate cake at the stage entrance midway through an exhausting run, sometimes a celebratory dance at the cast party. We also both lived in the East Village, and so often shared taxis to and from the airport, and occasionally a meal at a neighborhood Japanese restaurant.

Years later, when I returned to work for the Cunningham Dance Foundation, I attended a program that Kosugi gave in Madrid. He played music using an array of objects and devices on his table. Afterward he spoke about what he’d done, explaining that his music used sound waves and light waves, and that these waves were “part of nature.” This was an astonishing insight for me, that electronic music was not separate from nature, but derived from it.

AM 89. When Merce gave a work a title such as Cargo X, he tempted any of us to ask “What does he mean?” How much time did you give to such thoughts? Any ideas about X? or indeed Cargo?

PL 89. At the time, I didn’t make much of the title, although I assumed “cargo” referred to the ladder which got carted around during the dance. Merce had seen and then acquired the ladder from a theatre in Toulon during one of our recent tours.

In 2019, when I was doing research for my “On This Day” project, I ran across an interview in which Merce was asked about the title. He replied, “It’s made up. It can mean anything. Cargo means something going around and moving around, although it doesn’t have anything to do with the dance. And I thought that if I added an X that would confuse it all even further.” Make of that what you will!

AM 90. You’ve mentioned Signals (1970). Did you perform this in repertory or Events or both? What were the particular challenges and rewards of this work?

PL 90. I mostly danced Signals in Events, beginning in 1985. The dance was no longer in the repertory when I joined the company, but it was frequently done in Events. In 1988, we presented Signals as a repertory piece for a limited number of performances, but mostly we did it in Events.

The woman’s solo – originally made for Susana Hayman-Chaffey and during my early years danced by Susan Emery – was one of the most challenging things I ever had to do. It takes strength, courage, and focus. It was the courage that I had to develop. Merce put me into the part when I was quite new, and I think he did it to push me. I saw him give that solo to other up-and-coming dancers in the years following. He didn’t seem to mind watching dancers grapple with material, even on stage in front of an audience. He was patient in that way.

When I joined White Oak Dance Project in 1994, Signals was part of their repertory, so I ended up performing it many more times. In addition to the solo, my part included a duet which I did first with Alan Good (for MCDC) and later with Rob Besserer (for White Oak), and a playful, rigorous sextet.

AM 91. Did the woman’s solo involve a very pronounced hinge? I always remember your amazing courage in one solo that involved a hinge, but in Event context.

PL 91. Yes it did. Early in the solo the woman does a slow deep hinge from parallel relevé, and then, from the deepest point, springs back up in one swift move. A gratifying moment, especially when the hinge was very deep, and there were no wobbles after springing back up.

AM. I especially remember how you delivered that hinge at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, here in London, in autumn 1992. My friend Sally Rettig and I both gasped as we observed how you were leaning back onto the air.

AM 92. I only saw Field and Figures once, but David Vaughan felt it was one of Merce’s great works. The set and costumes were by Andrew Ginzel and Kristin Jones, the music by Ivan Tcherepnin. Is there a known reason why this didn’t last in repertory?

PL 92. Field and Figures was in the repertory for about two years, which was a common lifespan for a dance at that time. Merce was making three new dances a year, and we generally had about a dozen pieces in the current rep, so many dances cycled through and out in a couple of years. Merce may not have liked the design – I remember hearing some reservations about the large hanging objects.

AM 93. I believe it became known that Merce felt it was “about” the four elements. If so, did you know which element you were part of? Your memories of your role and this work?

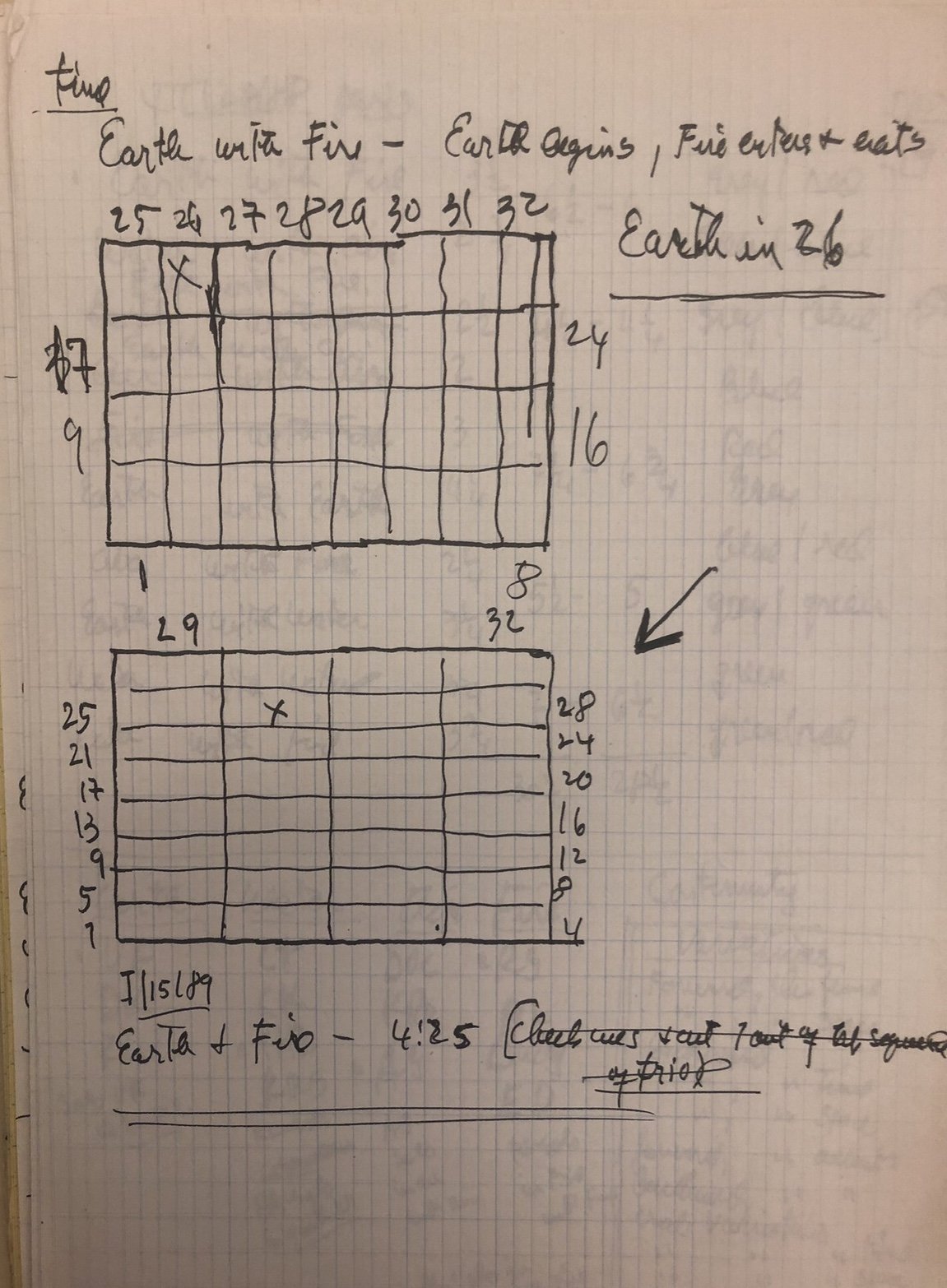

PL 93. We all knew about the four elements aspect of Field and Figures. This was not “confidential” information. We were divided into four groups. Vicki Finlayson, David Kulick, and Rob Wood were “Earth.” They did slow, weighted movement. Helen Barrow, Chris Komar, Kristy Santimyer, and Carol Teitelbaum were “Water.” Their movement was fluid and lyric – for me, the most compelling material in the dance. Kimberly Bartosik, Michael Cole, and Dennis O’Connor were “Air.” They jumped and jumped. Emma Diamond, Larissa McGoldrick, Robert Swinston, and I were “Fire.” We dashed about doing brisk, accented movement.

Recently I’ve looked at Merce’s choreographic notes and discovered more about the dance. As was often the case, Merce devised a gamut of 64 movement phrases for the dance, but in this case the phrases were divided into four sets of approximately 16 phrases, one set for each of the four elements. So each group had its own gamut. Merce used chance operations to determine the sequence of phrases done by each group.

The dance was structured so that each of the four groups (or elements) was on stage one time alone and one time paired with each of the other three groups. In addition to the elements, (which Merce refers to in his notes as Matter), he identifies two Forces: Gravity (“gravity to sink”) and Levity (“levity to rise”). He associates Earth & Water with Gravity, and Air & Fire with Levity. His notes include several working titles including Matter & Forces, Elements & Force, and Primeval Minn (the dance premiered in Minneapolis). We didn’t know these details at the time, but they ring true – they describe a dance that we knew intimately, but in a different way.

AM 94. It irritated you then that some critics couldn’t tell the difference between you and Helen Barrow. I was lucky in that I could tell that difference, but how would you describe that difference? You were friends, and you admired each other.

PL 94. Well, no performer likes to be mistaken or misidentified. But being mistaken for a dancer as elegant and refined as Helen is best taken as a compliment. Helen was an exquisite dancer, and she was and is a kind and generous person.

AM 95. Art Becofsky may have been the best executive director MCDC ever had until he became a nightmare. I’ve read many of the pages of applications he made that won funding for Cunningham premieres, for the Cunningham school and foundation, for the Cunningham archive; I’ve been aware that Cunningham dancers were made extremely unhappy in various ways, especially after the death of John Cage in 1992. Did you observe him change from one into the other? Can you enlarge?

PL 95. I’m disinclined to comment, aside from saying that I don’t remember a big change. Art Becofsky was who he was, and he did what he did.

AM 96. Your memories of Inventions?

PL 96. I haven’t looked at Inventions since I danced it. I remember the green costumes – all shades of green – and the bright orange backdrop, and the Cage music. The movement, as I recall, was classic Cunningham: triplets, jumps, leg extensions, turns. Lots of running in and out, and shifting combinations of people.

AM 97. August Pace and Inventions had their premieres on consecutive nights, another pair of stylistically contrasting works that Merce concocted more or less simultaneously. Again, do you feel Merce enjoyed working on unalike works at the same time? These were both important works.

PL 97. I think Merce enjoyed making work and was probably grateful that Cal Performances was able to support the creation of two new works in one year. As you say, August Pace and Inventions premiered on consecutive nights, September 22 & 23, 1989. But we had done a “preview” performance of Inventions two months earlier on July 23 in Arles. So by late July the choreography for Inventions was finished, and I think our rehearsals for August Pace were mostly in August. In other words, there was some separation. But it does make sense to me that the two dances would be so structurally different – one a series of duets that would allow Merce to be in the studio with one or two dancers at a time, and the other a dance with shifting combinations of groups, more of a “crowd scene.”

AM 98. Inventions had a Cage score that was tough on dancers and audiences. Yet this seems to have been the first new Cage score for MCDC in which Cage did not perform. Did the Cunningham enterprise feel different as Cage began to withdraw from active participation in it?

PL 98. Looking back, it’s easier to see that Cage was no longer part of the touring company, but at the time it wasn’t so clear that things had permanently changed, except that Michael Pugliese had joined Tudor and Kosugi as the regular group of musicians.

AM 99. Again, might the Trust consider reviving such a work with a revised score?

PL 99. Anything is possible, but “difficult for audiences” is not a compelling reason for revising a work. Sculptures Musicales, the Cage music for Inventions, is an extraordinary score. The abrupt loud sounds were startling and unsettling, and the intermittent silences and quiet sounds allowed the footfalls of the dancers to be heard. My guess is that if Inventions is revived, it will be because an artistic director is as fascinated as much by the Cage music as by the Cunningham choreography.

AM 100. In 2019, you spent time on Merce’s notes for August Pace. You discovered much about his compositional process. You were able to see how he had prepared you in his 1989 classes for the phrases he would use in his choreography, how he “spliced” phrases together, and how he gave a soloist role to someone he spotted had been well suited to a phrase in class. So much of the movement came from the classes he had given you all that, in theory, any of your fifteen dancers could have done any of the fifteen roles (apart from the trickier partnering aspects). What do you remember of those classes? Were you aware he was preparing a new work?

PL 100. Merce didn’t teach material in class in order to audition his dancers. By the time he taught the phrases in class, he had usually already worked out, using chance operations, who would do what. Teaching the phrases in class was practical and purposeful – Merce got to see how the movement worked in bodies and in space, and we began to learn about the physical tasks and priorities of the upcoming dance.

Earlier, you pointed out that Merce made Inventions and August Pace at nearly the same time – a huge undertaking. In addition to making those dances, he also taught company class two or three times a week. For every class, he had to devise a warm-up and then invent an adagio, two phrases that moved across the floor (usually one that was larger and slower, and one with fast footwork), a small jump phrase, and a big jump phrase. The summer Merce was making Inventions and August Pace, he built his classes from the August Pace gamut. It seems to me that he saved himself time and effort, and got the movement out of his body and into ours.

Merce was a genius – a practical and efficient genius.

AM 101. How often, over your nine or ten years, were you aware of Merce adjusting his classroom teaching to prepare you for his next work?

PL 101. Merce taught class several times a week for my entire tenure (and for decades before and decades after). His class was always a challenge, often exhilarating, and sometimes an ordeal. Over the years, Merce taught countless phrases in class, whether he was working on a new dance or not. But sometimes, there would be a phrase or a series of phrases that seemed a little different, a little more charged or nuanced or rhythmically complex. That’s when I knew that a new dance was about to come our way.

@Alastair Macaulay 2022

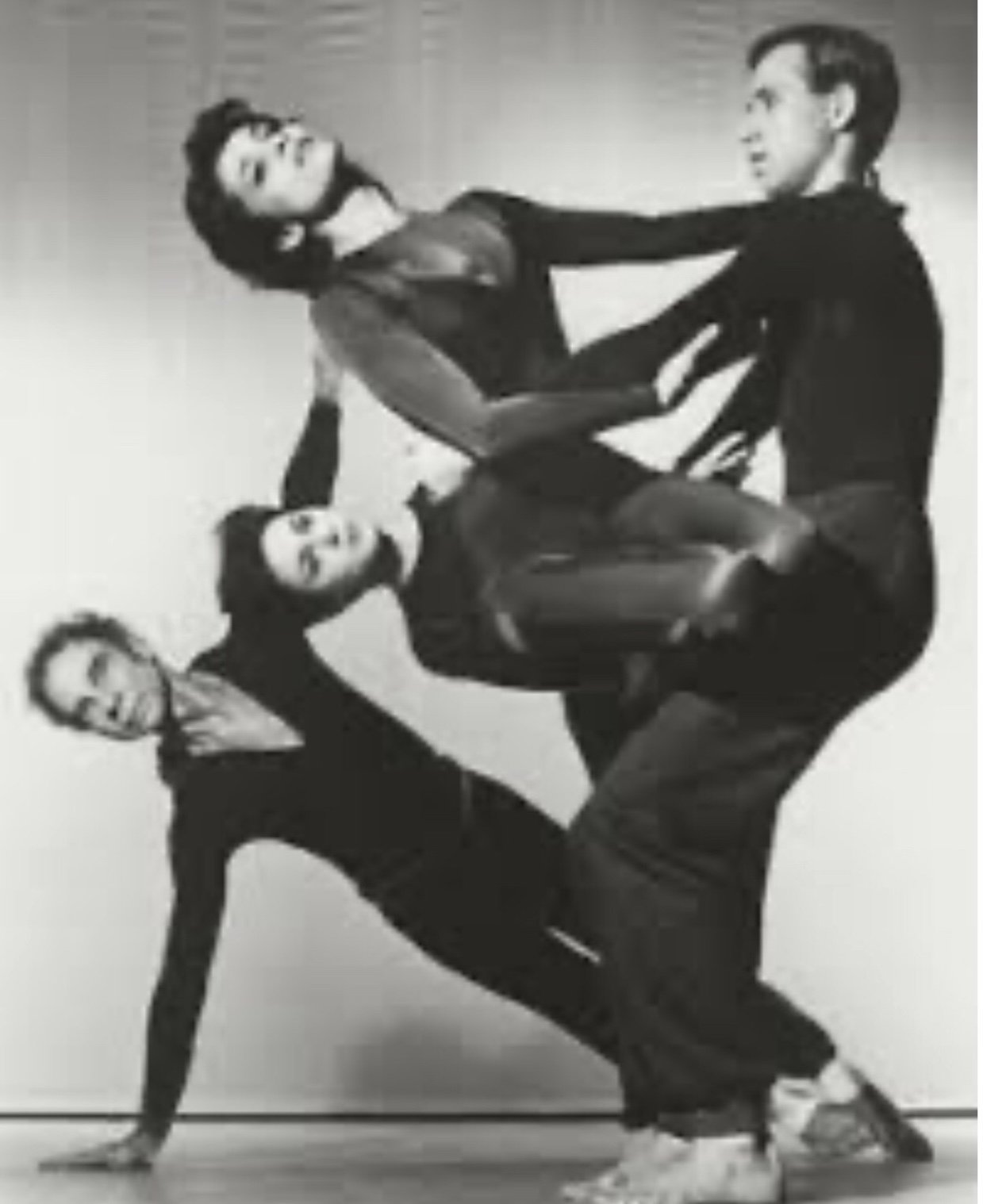

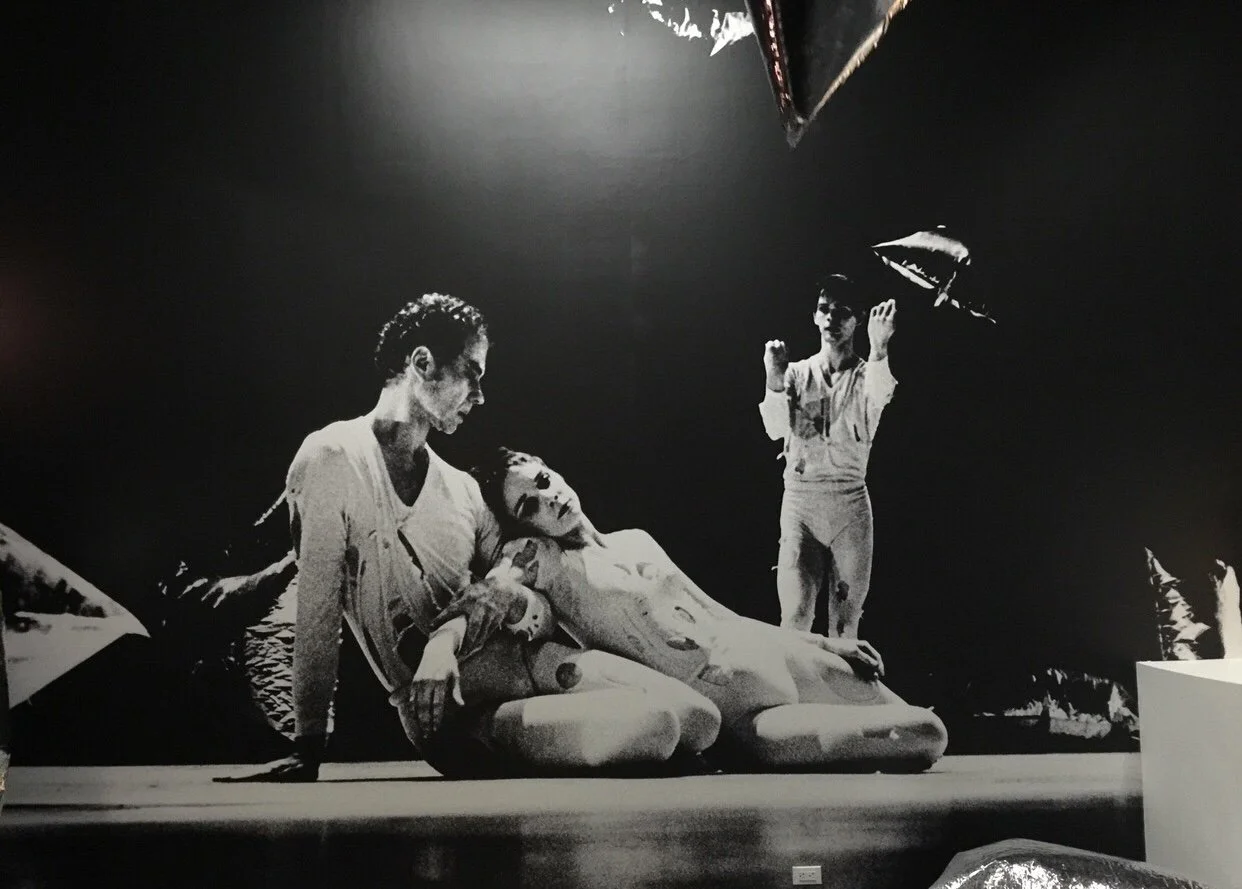

1: Studio photograph of Merce Cunningham’s Quartet (1982), with Cunningham (left), Helen Barrow, Judy Lazaroff, Rob Remley.

2: The composer and musician David Tudor (1926-1996), who toured with the Cunningham company for well over thirty years. Having been a virtuoso pianist of radical modernist music from the 1950s on, and a close colleague of John Cage’s, he became a composer and player of electronic music. Cunningham, for his RainForest (1968) commissioned Tudor’s first score, Rainforest. After that, Tudor composed a number of electronic scores for Cunningham, including Toneburst for Cunningham’s Sounddance (1975) Phonemes for Cunningham’s Channels/Inserts (1981), Sextet for Seven for Cunningham’s Quartet (1982), Webwork for Cunningham’s Shards (1987), and Neural Network Plus for Cunningham’s Enter (1992). Cage’s death, Tudor became the Cunningham company’s musical director.

3: David Tudor at his electronic keyboard.

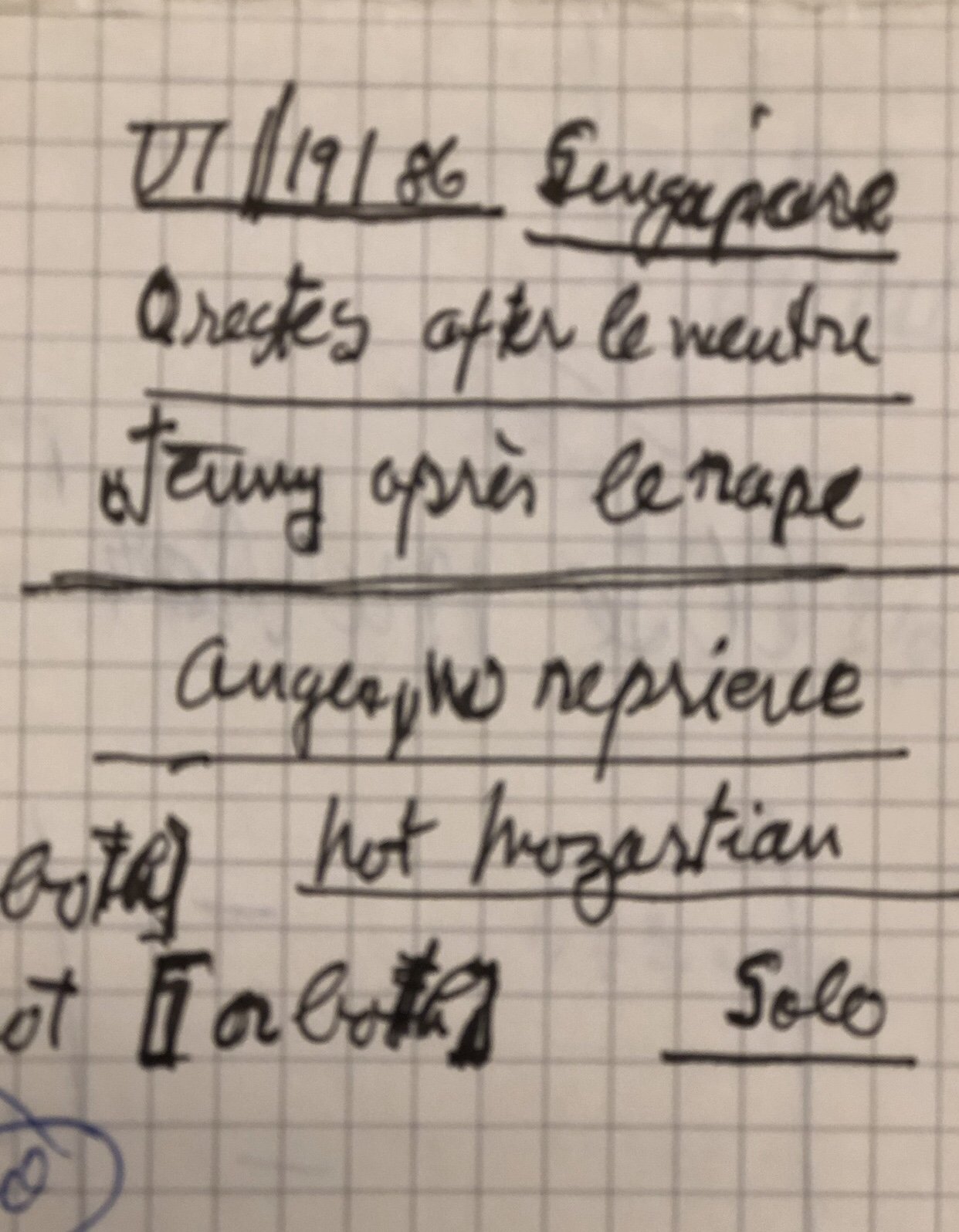

4: The first page of Merce Cunningham’s notes, dated 19 June 1986 (“VI/19/86”), for the work that became Shards (1987). See details in illustrations 5 and 6. Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

5: Detail of first page of Cunningham’s notes for Shards (1987), beginning with “Grief to wail: 15 movements”. These notes are among the strongest evidence that Cunningham sometimes, if infrequently, began his works as an Abstract Expressionist, seeking to show emotion. The emotion in Shards, however, may not have been Cunningham’s own but those he observed in mentally disturbed homeless people who had been released from institutions under Ronald Reagan’s presidency.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

6. Detail of 5: the top right-hand page of Cunningham‘s first page of notes for the work that became Shards (1987). The date (“VI/19/86”) is June 19, 1986, the location in which Cunningham writes is Singapore. The following five notes are separate ideas for possible subject-matter: “Orestes after le meurtre”, “Jenny après le rape”, “Anger, no reprieve”, “Not Mozartian”, “Solo”. Orestes, the famous character in Greek mythology best known for killing his mother Clytemnestra, was the name of a solo Cunningham had made for himself in 1948. (My own belief is that each of these headings was Cunningham’s idea of a mentally disturbed person made recently homeless.)

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

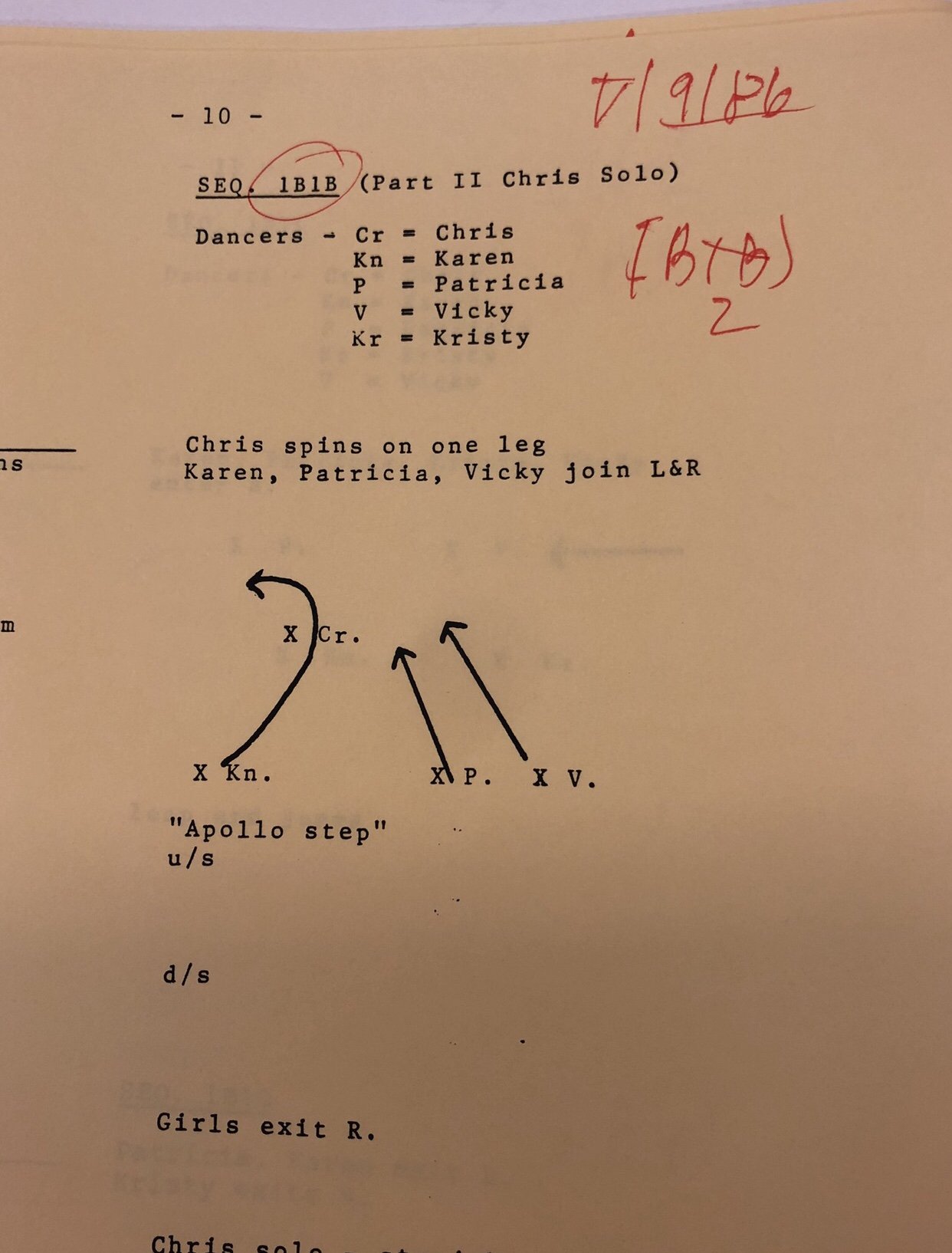

7: One page of Merce Cunningham’s preparatory notes for Points in Space, first made as a dance film for BBC-TV (filmed in 1986 in London, screened in 1987) and then adapted as a stage work in 1987. The reference to a Max Ophuls film indicates Cunningham’s extensive if not expert knowledge of films.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

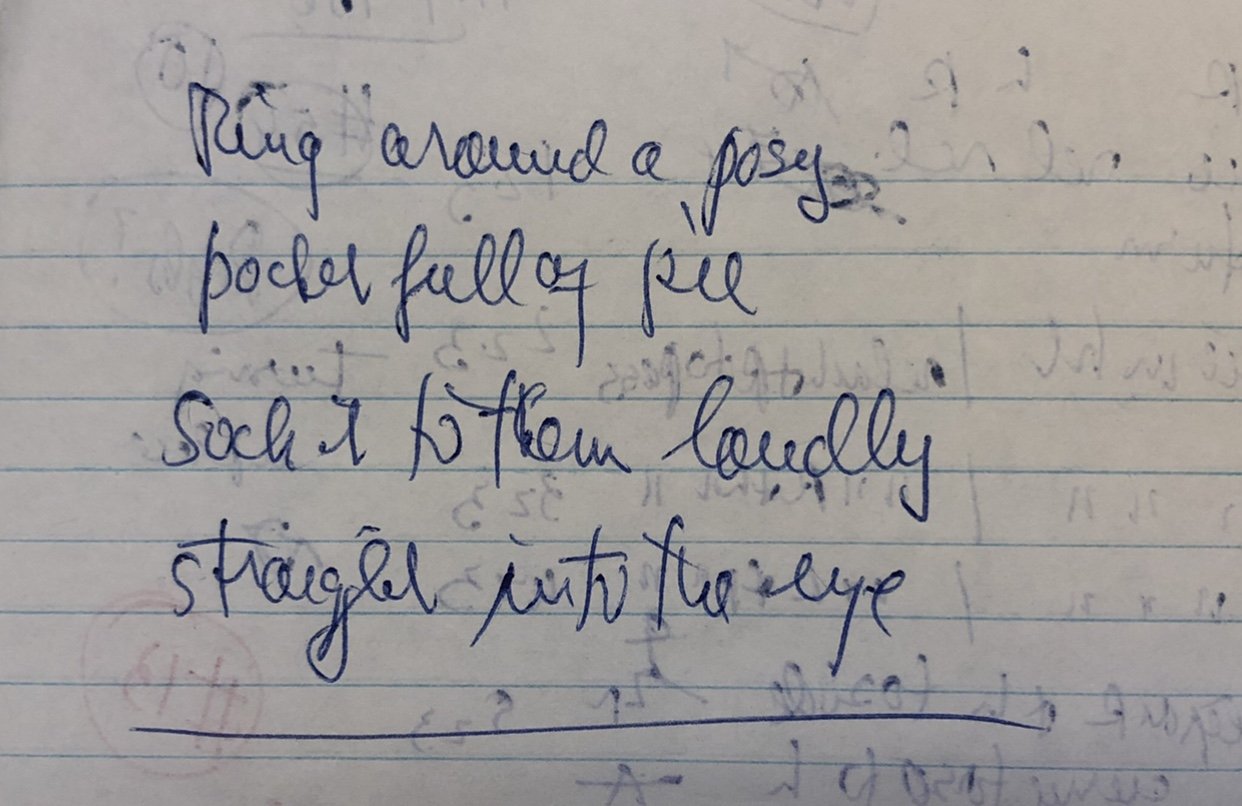

8: A page, dated March 1986 and located Detroit (lobby of Westin Hotel), of Cunningham’s notes for Points in Space (1987).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

9: A later page (May 9, 1986) of Merce Cunningham’s notes for Points in Space. The names refer to Chris Komar, Karen Fink Radford (later Karen Eliot), Patricia Lent, Victoria (Vicky/Vicki) Finlayson, Kristy Santimyer.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

10: A still photograph from the TV film of Merce Cunningham’s Points in Space (1987).

11: A still photograph of the TV film of Merce Cunningham’s Points in Space (1987).

12: The musician and composer Takehisa Kosugi (1938-2018). He toured as a Cunningham musician with the company for many years; he composed a number of scores for Merce Cunningham, including those for Doubles (1984, Spacings) and Cargo X (1989, Spectra).

13: An initial page of Merce Cunningham’s notes for his Carousal (1987).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

14: Another page of Merce Cunningham’s notes for his Carousal (1987).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

15: Another page of Merce Cunningham’s notes for his Carousal (1987).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

16: Another page of Merce Cunningham’s notes for his Carousal (1987).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

17: Another page of Merce Cunningham’s notes for his Carousal (1987).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

18: Another page of Merce Cunningham’s notes for his Carousal (1987).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

19: Another page of Merce Cunningham’s notes for his Carousal (1987).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

20: An early scene in Merce Cunningham’s RainForest (1968). Cunningham (left) and Barbara Dilley (centre) are approached by Albert Reid (right).

21: A year after the 1968 premiere of his RainForest, Merce Cunningham said that it had been inspired by his reading of the anthropologist Colin M. Turnbull’s book, The Forest People (1961). There is no close correspondence, however, between Turnbull’s book and Cunningham’s stage work.

22. Cunningham’s initial notes for the dance that became Five Stone Wind (1988) began in March that year with his giving it the Russian name for The Cherry Orchard (Peter Brook’s production of Chekhov’s play had recently played at the Brooklyn Academy of Music). He then began planning his new work’s dramaturgy according to the entrances and exits of Chekhov’s play, beginning with “Lopakhin” and “Dunyasha” (in Cyrillic script). Cunningham had taught himself to read and write Russian in the 1950s.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

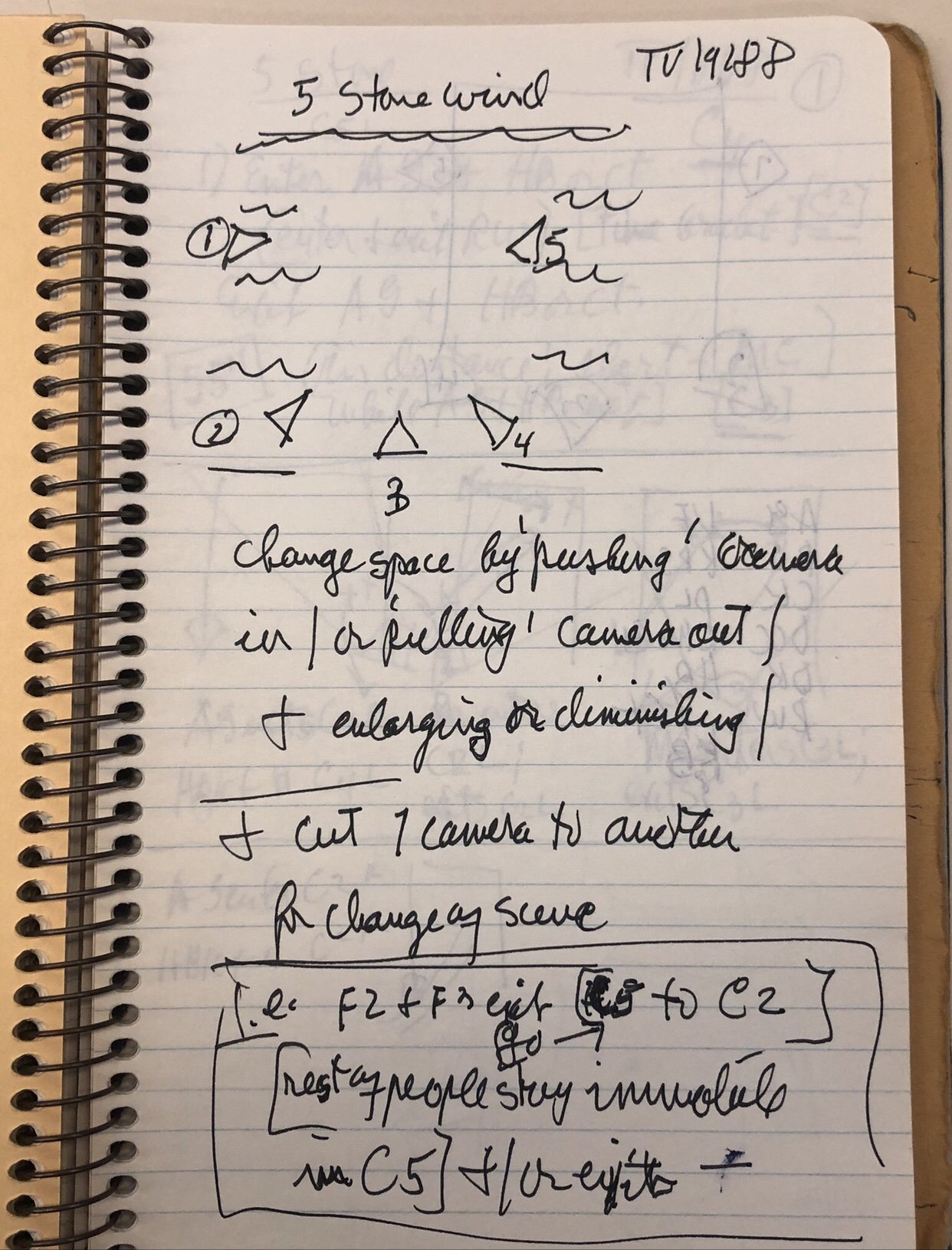

23: In the preparatory notes written the next month, April 1988, Five Stone Wind has gained its eventual name.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

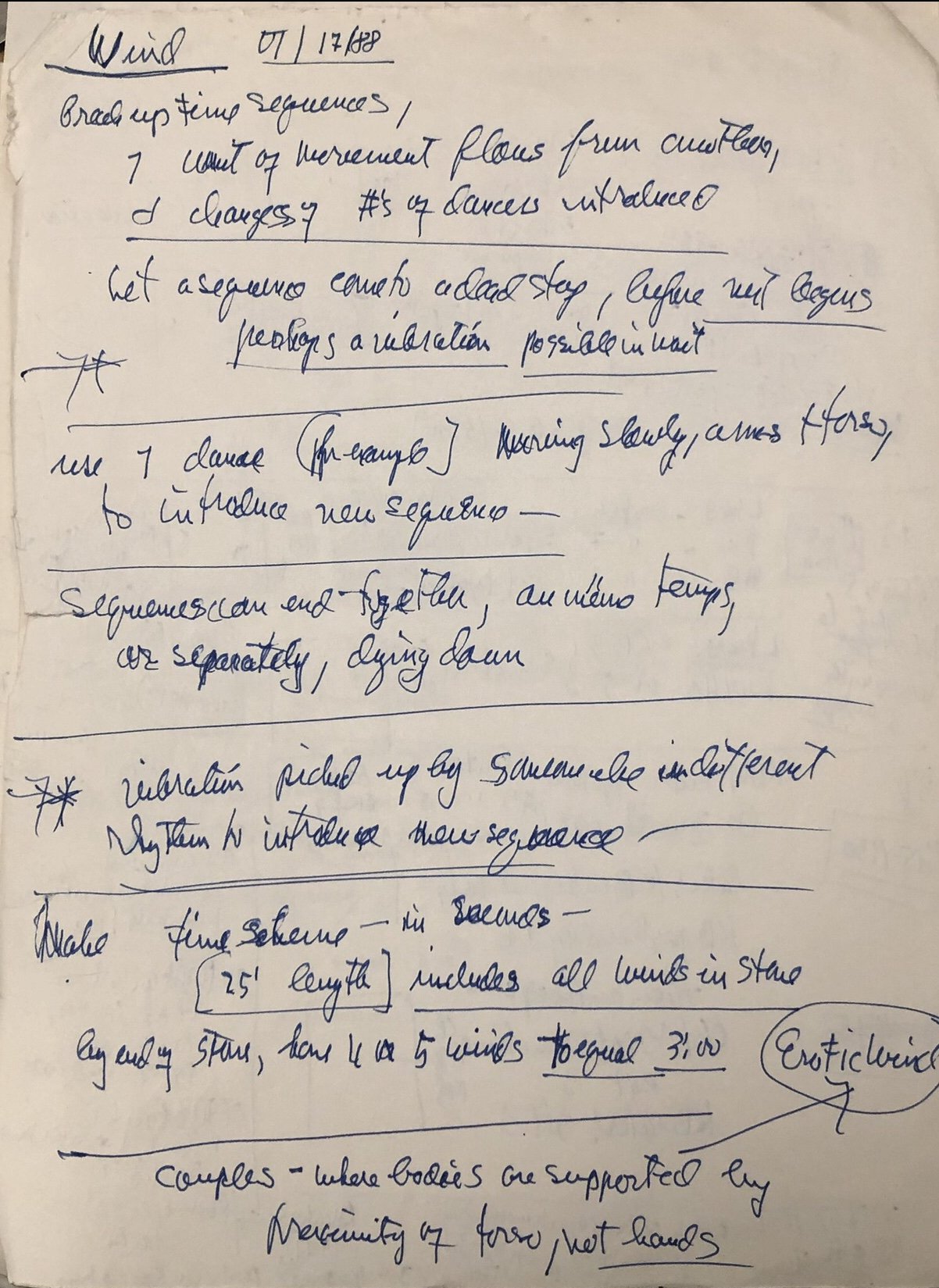

24. A later preparatory page (June 1988), focused on the “Wind” element of Five Stone Wind.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

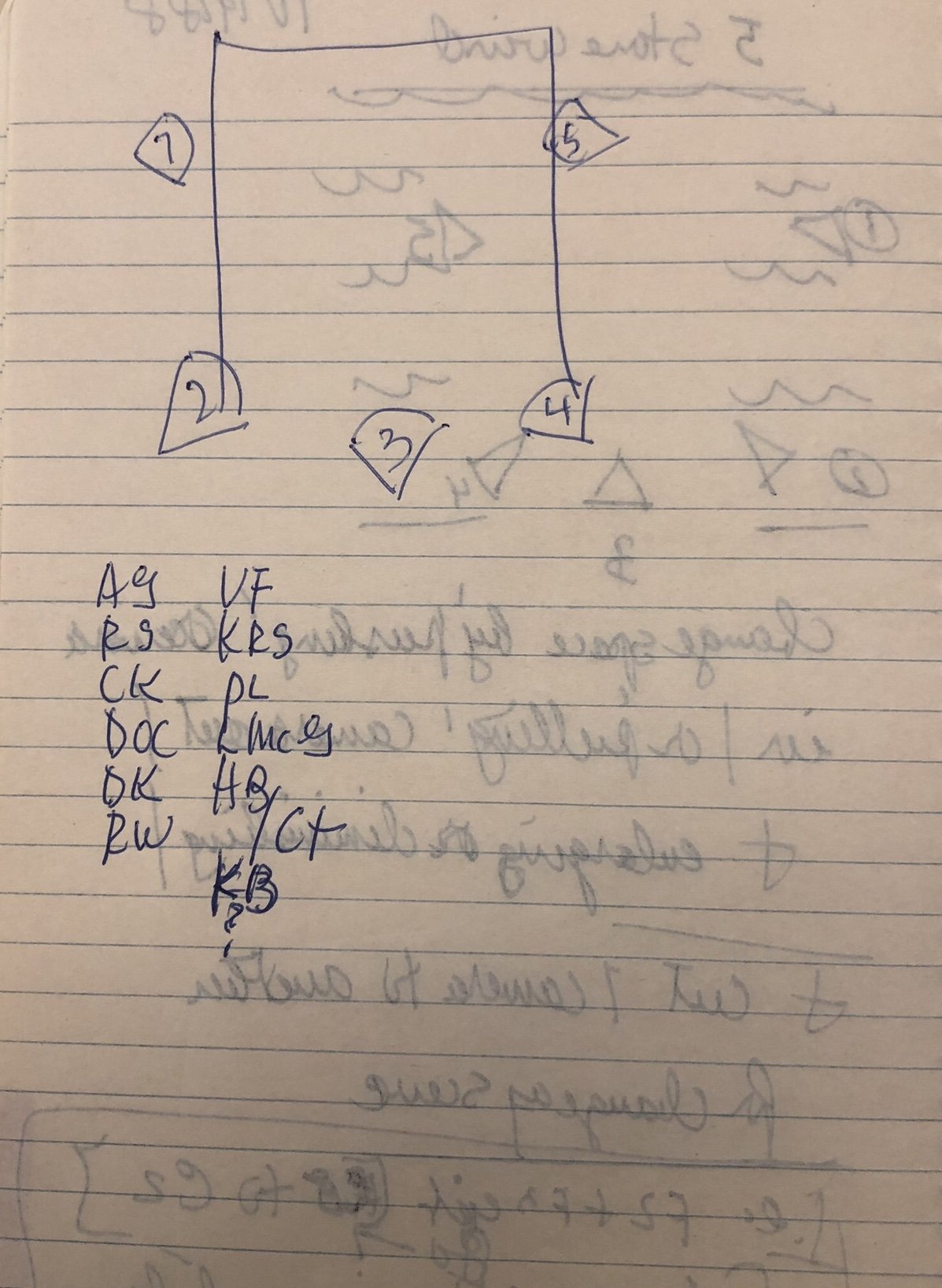

25: A page of notes showing the “five” of the title of Five Stone Wind in terms of the stage. The initials are those of the 1988 dancers.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

26: Cunningham’s idea for Cargo X (1989) seems to have begun with a ladder he spotted on a French tour in 1988. This early page of notes shows some of his visual ideas, before the work gained its eventual title.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

27: A subsequent page of Cunningham’s “Ladder moves” notes for the work that became Cargo X (1989).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

28: Some of Cunningham’s notes for Field and Figures (1989) confirm what all the dancers learnt in rehearsal, that Cunningham was thinking of the four elements. The audience did not have this information.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

29: Cunningham’s planning for two of the four elements in the work that became Field and Figures (1989).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.

30. A further preparatory page of Cunningham’s notes for Field and Figures (1989).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dance Division of the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust.