An Ashton triple bill at Covent Garden, April-May 2022

To watch the three ballets by Frederick Ashton that have now re-entered Covent Garden repertory is to be brilliantly bombarded by high-style sensation. The effect is more sensuously kinaesthetic than with any other choreographer; no other choreographer matches him for showing the interplay between our social surface and our inner impulse.

Scènes de ballet (1948, to Stravinsky’s 1944 score of that name) was the ballet that Ashton was always proudest of having made. Often, here, small steps for feet coincide, rhythmically, with sharp flicks of wrists and sudden Janus turns of the head from one profile to the other - even while the torso and pelvis stay sculpturally still. Yet in other sequences the dancers’ backs, torsos, and thighs are powerfully energised. The ballerina’s second solo has a hopping phrase in which she, holding a grand arabesque line, toyingly flourishes her right wrist this way and that, as if seeing how a bracelet might catch the light. Yasmine Naghdi, Saturday evening’s ballerina, has never had a role better suited to her: her admirable array of skills here acquire charm and authority. The more experienced Sarah Lamb, at the matinee, should be equally fine, but performs tensely, without spontaneity.

These are just topmost details in a work whose polyrhythms and changing spatial architectures are of dazzling sophistication. You hear all the many facets of Stravinsky’s score better for watching.

A Month in the Country (1976) is an ingenious rearrangement of Turgenev’s play of the same name (1872). As long as the drama stays an affair of multiple narratives, Ashton’s poetic touch is uncanny. The young student hero, Beliaev, has three pas de deux in quick succession with different women, marvellously differentiated. And, in the most multifaceted portrait of a woman in ballet repertory, the lady of the house, Natalia Petrovna, is wife, guardian, mother, lover to four other characters.

When Ashton brings Beliaev and Natalia together for a sustained pas de deux, he does so at first gorgeously. Natalia’s melting, passionate responsiveness to Beliaev is beautifully shown, without losing her riveting tendency to self-dramatise. Yet it’s here that Ashton turns the drama firmly away from Turgenev’s tough-minded comedy into wistful sentimentality. True, he does so with perfect theatrical skill, but it takes considerable subtlety to prevent the wistful final business with a rose becoming mawkish. Matthew Ball (matinee), an unsophisticated Adonis, would be an ideal Beliaev except that his marvellously focused acting makes him too conscious of his effect on women. Marianela Nuñez, his Natalia, plays everything with unswerving charm and sophistication but without the touches of blunt self-awareness that should undercut the sentimentality. Laura Morera (evening) has those touches and more; at the end, she’s both stunned and desolate. Vadim Muntagirov, her Beliaev, is internationally admired as the most stylish of virtuosi, yet, touchingly here, he seems never to lose innocence.

In Rhapsody (1980), there are several points where the choreography has been changed since Ashton’s death. The choreography for the central pas de deux has also a jarring non-sequitur that no cast has ever solved: one moment the bravura hero holds his ballerina aloft while she seems to peal chimes in the music with her hands, the next she’s snuggling surreptitiously under his arm as if to say “It’s only little me”. Yet Rhapsody, these flaws notwithstanding, is the peak experience of this Ashton programme. Bubbling over with points of style, it makes us feel again that Ashton’s genius for exuberant physical sensuousness. You can sense the Covent Garden audience catching its breath and moving helplessly in its seats.

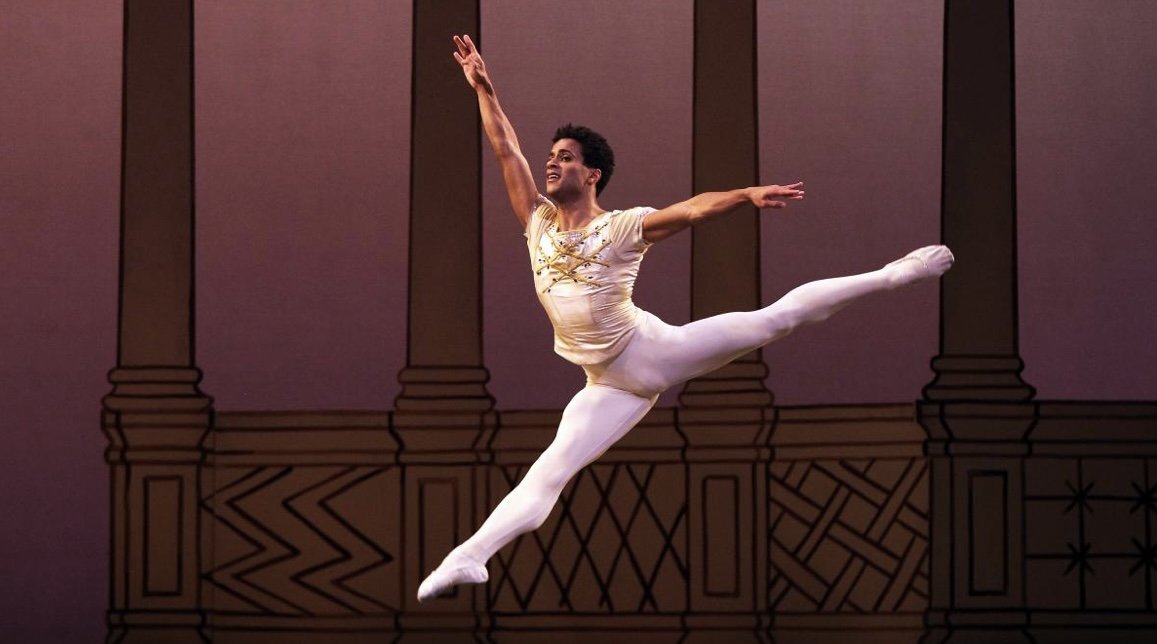

Francesca Hayward and Marcelino Sambé (matinee) are in many ways an unlikely couple. He has thrilling physical force, whereas the rapid footwork she shows here is against the grain for her. Yet they dance like kindred spirits, with a love of playfulness and rhythm and suspense. He has the most startling of all the ballet’s many sudden changes of direction, jumping powerfully in a sequence of opposite directions; but he also relishes the succulent adagio phrases, his strong legs lusciously yielding in demi-plié. Hayward in one moment is delectable in rippling renversé impulses that make the spine yield and arch at top speed; in the next sequence she makes sudden declarations of full-bodied line that beam forth like beacons. Anna Rose O’Sullivan (evening), an often scintillating virtuoso, hasn’t yet found the dynamic contrasts for this role, though it’s likely she soon will. Steven McRae, still working his way back from a long injury, begins by husbanding his resources, cleverly, in a bravura role, then starts to let rip after the pas de deux.

Plenty of Ashton’s finest choreography goes to the surrounding ensemble of six women and six men. The young Royal dancers, all born since Ashton’s death in 1988, all take to this to the manner born. Rhapsody’s most irresistible dance is the ebullient champagne number for six women that immediately follows the pas de deux. It’s exuberant today as it was in the year of its making.

1: Sarah Lamb with Vadim Muntagirov in Frederick Ashton’s Scènes de ballet. Photograph: Helen Maybanks.

2: Marianela Nuñez (Natalia Petrovna) and Matthew Ball (Beliaev) in Frederick Ashton’s “A Month in the Country”. Photograph: Tristram Kenton.

3: Marianela Nuñez (Natalia Petrovna) and Matthew Ball (Beliaev) in Frederick Ashton’s “A Month in the Country”. Photograph: Helen Maybanks

4: Gary Avis (Rakitin), Marianela Nuñez (Natalia Petrovna), Christopher Saunders (Yslaev) in Frederick Ashton’s “A Month in the Country”. Photograph: Helen Maybanks.

5: Marcelino Sambé partnering Francesca Hayward in Frederick Ashton’s “Rhapsody”.

6: Marcelino Sambé in Frederick Ashton’s “Rhapsody”.